Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 19, 2024

This is Part 16 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

Last time, I mentioned the problem of designing efficient data structures for Prolog's lookup process.

The heart of our logic-oriented gameplay system lies on the evaluation of rules, which in turn requires the system to quickly search for relevant pieces of data without too much friction. And for the sake of fulfilling such a purpose, I introduced the idea of using sets and dictionaries (i.e. hash tables) to store parts of the game's state (aka "facts").

From a purely conceptual point of view, the current state of our game world can simply be imagined as a long list of facts, such as: "My dog ate my homework yesterday", "This tuna was frozen at 4:00PM today", "This object is a cheeseburger", and so on. And the primary job of our Prolog engine is to apply these given facts to the game's rules (i.e. horn clauses) and infer new facts out of them.

This is where most of the performance issues stem from. In order to apply facts to the rules, you must first search for facts which are applicable to those rules. And to achieve this, you need clever algorithms and data structures to help the system undertake this "searching" portion of the game loop as swiftly as possible. If you repeatedly iterate the entire list of facts without employing shortcuts (such as hashing), you will soon find yourself hitting the performance bottleneck.

As I illustrated in the previous article (Part 15), storing facts inside hash tables (e.g. sets and dictionaries) and using keys to reference them is one of the most obvious ways of mitigating the performance issue. The main design problem with this has to do with the matter of choosing which arguments to use as keys.

A fact often consists of multiple arguments, and we are obliged to treat at least one of them as the key for dictionary lookup. And the most optimal choice of the key really depends on the manner in which the fact is being regarded by the rules.

Let me demonstrate what I mean by this. First of all, here is an example of why the overall performance of the system might vary drastically depending on the choice of keys (See the code below). It is just one of the rules from Part 5, which tells us that two actors must be "colliding" if their positions coincide.

collide[n](X, Y) :- position[n](X, P), position[n](Y, P).Here, we are able to see two types of relations - "collide" and "position". Let us see how their data storage shall be implemented.

I will begin with "collide". A fact of type "collide" simply tells us that the two given actors are colliding with each other (i.e. their positions are identical). If I decide to record all such incidents of collision inside a dictionary, which of the two actors (X, Y) should I choose as the dictionary's key? The first one? The second one? Or... both of them put together as a tuple (because "collide" is a symmetric relation, meaning that both of the actors involved are subjects of equal importance)?

From a conceptual perspective, it definitely makes sense to consider both of the two actors as part of the key because nothing suggests us to prefer one of them over the other. We ought to contemplate upon the usefulness of such a construct, though. For example, suppose we devised the storage of "collide" relationships as a set of colliding pairs of actors, like the one shown below.

public HashSet<(string, string)> collide;This data structure is able to immediately answer questions such as: "All right, here are two actors. Are they colliding or not?"

It expects the questioner to already know who these two actors are - just not whether they are colliding. And as long as a pair of actors are given, this set will instantly answer the question with almost no delay. But the thing is, do we really need this functionality, in the context of gameplay?

If we were developing, say, a car insurance program in which the main goal is to figure out whether a pair of known clients were involved in the same car accident, the above implementation would have been a pretty cool design choice. Unfortunately, I am supposing here that we are trying to develop video games.

A game engine usually does not just take a look at an arbitrary pair of actors and check if they are colliding or not. Instead, it looks at each actor and tries to answer the question: "Who's colliding with this guy?"

When it comes to game programming, therefore, it is more sensible to represent instances of collision as key-value pairs, where the key is one of the two colliding actors and the value is that other guy that the actor is bumping into.

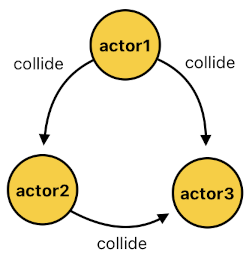

public Dictionary<string, HashSet<string>> collide;This means that, if we imagine that there are three actors called "actor1", "actor2", and "actor3", and proceed to declare that "actor1" is simultaneously colliding with both "actor2" and "actor3" while "actor2" is colliding with "actor3" (See the list below),

FACTS:

collide[0](actor1, actor2).

collide[0](actor1, actor3).

collide[0](actor2, actor3).

We will have to store these facts as actor-to-actor mappings, like the ones displayed below:

public class Facts

{

public Dictionary<string, HashSet<string>> collide;

public void Init()

{

collide["actor1"].Add("actor2");

collide["actor1"].Add("actor3");

collide["actor2"].Add("actor3");

}

...

}This will allow the system to quickly find out all the actors which happen to be colliding with "actor1", for example.

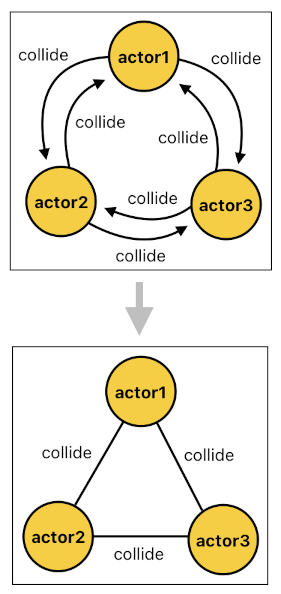

At this point, though, you may be wondering, "Okay, what if I want to know which actors are colliding with 'actor3'? This dictionary only has 'actor1' and 'actor2' as its keys, so it only directly answers questions regarding which actors are colliding with one of these two actors, and not 'actor3'!"

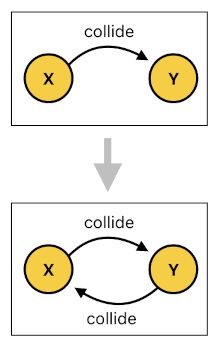

This is a totally valid concern, and it definitely means that we need to rectify our logic a bit to take into account the symmetric nature of collision. The way we solve this is not that complicated; all we need is just an extra rule in our Prolog code, which is shown here:

collide[n](Y, X) :- collide[n](X, Y).

This rule is the declaration that collision is a commutative relation (i.e. a relation which still holds even if you change the order of its arguments). It basically says that, if X is colliding with Y, then Y must be colliding with X as well. The presence of such a rule will ensure that facts regarding collision will always come in pairs, where both of the colliding agents are guaranteed to be included as keys in the dictionary.

FACTS:

collide[0](actor1, actor2).

collide[0](actor2, actor1).

collide[0](actor1, actor3).

collide[0](actor3, actor1).

collide[0](actor2, actor3).

collide[0](actor3, actor2).

So, under this new rule, the system will be able to discover the fact that "actor1" and "actor2" are colliding with each other either by looking up the dictionary with the key "actor1", or by looking up the dictionary with the key "actor2". Either approach will work equally well.

(Side Note: This additional rule, "collide[n](X, Y) :- collide[n](Y, X)", won't even be necessary as long as the collision detection rule manages to infer both "collide[n](X, Y)" and "collide[n](Y, X)" from every colliding pair of actors X and Y. Therefore, it should be taken as a mere demonstration of the concept.)

This pretty much sums up the nature of the "collide" relation, and how it should be represented in a dictionary. How about the "position" relation - the one which is being used to derive facts regarding the status of collision between two objects?

collide[n](X, Y) :- position[n](X, P), position[n](Y, P).The rule which is responsible for this process (shown above) expects two relations to be satisfied, and both of them are of type "position". It essentially asks the interpreter to find out a pair of "position" facts - one which tells us the position of actor X, and the other one which tells us the position of actor Y. If these two facts both happen to be associated with the same exact position (denoted by the variable "P"), the rule will conclude that X and Y are colliding with each other.

In order to infer new facts out of this rule, the interpreter will of course have to search for a pair of facts of the type "position". This will involve two dictionary lookups, I presume. So, let me first format the dictionary which is going to be searched. Here we go:

public Dictionary<string, Vector2> position;This one stores a bunch of key-value pairs, where the key indicates an actor and the value indicates the actor's position (i.e. a vector quantity). Pretty straightforward, huh?

If the system is to evaluate the aforementioned rule, then, it will first take a look at "position[n](X, P)" and say, "Okay, I will need to go over all the entries in the 'position' dictionary because I do not know what X and P are."

Such an exhaustive search process, of course, can be expressed as a simple for-loop (See the code below).

foreach (var kvp in position)

{

var X = kvp.Key;

var P = kvp.Value;

...

}In each iteration, the interpreter will be presented with a unique combination of X and P, where X denotes an actor and P denotes the actor's position. In order to satisfy the rule, it must also take a look at the second relation (i.e. "position[n](Y, P)") and check if there is any existing fact which matches the pattern: "position[n](Y, P)".

The interpreter already knows what P is; it's whatever "P" it happens to be given during the current iteration of the for-loop (i.e. the "Value" part of the key-value pair: "kvp"). Let us say that, according to the current iteration, "P" turns out to be <2, 3>. This will make the system face the following relation:

position[n](Y, <2, 3>)Since P is known, the only thing remaining to be identified is Y. Once we manage to find a value of Y which matches the pattern "position[n](Y, <2, 3>)", we will be able to satisfy all the conditions of the rule and thereby infer a new fact out of it. And in order to find out all such values of Y, we must search for all the existing facts which begin with the word "position", belong to time "n", and have <2, 3> as the second argument.

The problem is that the existing dictionary (the one I showed you before) is not so optimal for performing this type of search. It uses the first argument of the "position" fact (i.e. actor) as the key, which makes it highly efficient for looking up a given actor's position. Yet, when it comes to looking up an actor based on a given position, it proves itself to be terribly slow.

When we know the actor but not the position, all we have to do is simply feed the actor to the dictionary as the key and look up the position to which the actor corresponds. When we know the position but not the actor, on the other hand, we cannot simply feed the position to the dictionary to instantly look up its corresponding actor because a position (i.e. a vector quantity) cannot be used as a key.

If we decide to use this dictionary alone, therefore, we will be forced to iterate through the entire dictionary just to find an actor which happens to be located at the given position. This will basically be the same thing as running a for-loop inside the outer for-loop, like the one shown below.

foreach (var kvp in position)

{

var X = kvp.Key;

var P = kvp.Value;

foreach (var kvp2 in position)

{

var Y = kvp2.Key;

var P2 = kvp2.Value;

if (P == P2)

{

// Rule Satisfied!

AddFact(new Fact("collide", n, X, Y));

}

}

}Here, for each combination of X and P in "position[n](X, P)", we are scanning every possible combination of Y and P in "position[n](Y, P)". And whenever the inner loop's P happens to match the outer loop's P, we conclude that the current combination of X and Y matches the pattern of both "position[n](X, P)" and "position[n](Y, P)", suggesting that the rule is satisfied and we are able to infer a new fact called "collide[n](X, Y)" based upon the current combination of X and Y.

This methodology definitely works, but we know that a nested for-loop will be a real performance killer unless we are looping over just a handful of elements.

If there are 1000 actors inside the game world, for instance, the outer loop will have to run for 1000 times. This is already quite a load of work. And guess what? The inner loop will have to run for 1000 times for every iteration of the outer loop, meaning that the total number of loops is 1,000 x 1,000 = 1,000,000. A million! This is outrageous.

Here is the thing, though. Do we really need to use just a single dictionary to look up the entries? Can't we just create another dictionary which uses positions as the keys and actors as their corresponding values instead, so that searching for facts which match the pattern of "position[n](Y, P)" will be nearly instantaneous as long as P is known?

Of course, having two dictionaries for the same relation called "position" will indeed require the system to allocate a lot more space in memory. If we can reduce the overall time complexity of our collision detection logic from O(N^2) to O(N) just by doing this, however, wouldn't it be worth the sacrifice?

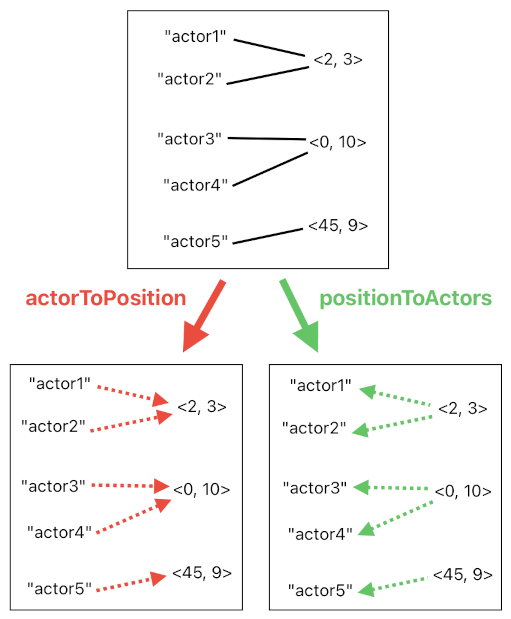

Let me show you how this works. Suppose that, instead of just a single dictionary called "position", we now have two dictionaries called "actorToPosition" and "positionToActors". The first one maps actors to positions, and the second one maps positions to actors.

public Dictionary<string, Vector2> actorToPosition;

public Dictionary<Vector2, HashSet<string>> positionToActors;

Since each actor is allowed to have only one position at a time (unless it's a quantum particle or something), it will be sensible to map each actor to a single vector quantity in "actorToPosition". In contrast, we are assuming here that multiple actors are capable of sharing the same exact position. Thus, it will be sensible to map each position to a set of associated actors (not just one actor) in "positionToActors".

Here is the idea. We have been dealing with both the outer loop and the inner loop, right? Let us make the outer loop visit all the entries in "actorToPosition" because each entry in this dictionary will tell us the position of each unique actor (It is not our desire to visit the same actor multiple times, hence the reason why we are preferring "actorToPosition" over "positionToActors" here).

Inside the outer loop, let us create an inner loop which goes through the entries of not the entire dictionary of actors and their respective positions, but only the set of actors which are located at the currently identified position (i.e. P). The following code illustrates the way it will be done.

foreach (var kvp in actorToPosition)

{

var X = kvp.Key;

var P = kvp.Value;

foreach (var Y in positionToActors[P])

{

if (X != Y)

{

// Rule Satisfied!

AddFact(new Fact("collide", n, X, Y));

}

}

}The number of entries in "positionToActors[P]" is just the number of actors which are overlapping at position P. This is a negligibly tiny fraction compared to the total number of actors in our game world. Thus, we can safely conclude that this revised search algorithm possesses the time complexity of O(N), where 'N' is proportional to the total number of actors. This is a great improvement.

What is happening here is very easy to understand, as long as we express it in plain English. First, we take a look at each actor and check its position. Then, we find all the other actors which are located at the same position, and say that they must be colliding with this particular actor.

But of course, our Prolog interpreter probably won't recognize the subtlety of this search problem automatically. Therefore, it will be necessary for us to explicitly specify the arguments which are to be used as keys in the dictionary.

To fulfill such a goal, let me introduce an additional notation to our custom Prolog language - "[key]". When attached in front of an argument, it will ask the interpreter to use it as the key when looking up the data entries. So, if I rewrite the collision detection rule like this:

collide[n](X, Y) :- position[n]([key]X, P), position[n](Y, [key]P).The interpreter will use each X as the key for finding all the matching instances of P, and use each P as the key for finding all the matching instances of Y.

This, however, still does not tell the Prolog system that each actor can only have up to 1 position (i.e. The "actorToPosition" dictionary should have "Vector2" as its value type instead of "HashSet<Vector2>"). Clarifying this point is crucial because we do not want the interpreter to create a HashSet just to store a single element in it.

For such a purpose, we will need to come up with yet another notation - "[single]". Attaching this in front of an argument will imply that it only permits a single value for each key. The following code, for instance, makes sure that the type of our "actorToPosition" dictionary is "Dictionary<string, Vector2>" instead of "Dictionary<string, HashSet<Vector2>>".

collide[n](X, Y) :- position[n]([key]X, [single]P), position[n](Y, [key]P).(Will be continued in Part 17)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service