Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 16, 2024

This is Part 15 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

In the last article, I spent quite a bit of time demonstrating our "hypothetical Prolog game engine" in action. If you have gone through my seemingly verbose step-by-step description of what is supposed to happen during the application's runtime, you would have recognized a common protocol via which the code is expected to be interpreted.

Instead of just hopping from one example to another and making case-by-case analysis, I will try to write an actual piece of code which may reflect the underlying logic with a fair amount of accuracy. It may not be directly written in Prolog, since I am assuming here that Prolog itself could be treated as a scripting language which is embedded within a more general-purpose programming environment.

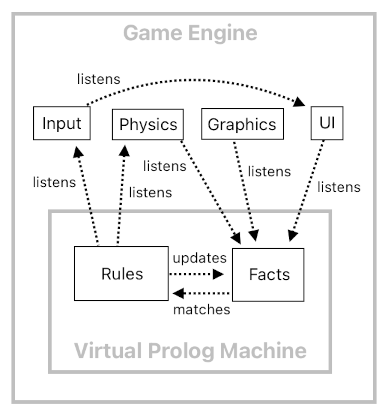

Imagine that we are constructing our own custom game engine which consists of two major parts - outer part and inner part.

The outer part is written in a popular programming language such as C#, which runs on Unity or some other easy-to-use development framework. This way, we will be able to conveniently build portions of the game which do not necessarily offer distinctive benefits when they are written in Prolog. For instance, I do not think that writing the entire graphics engine (e.g. OpenGL) using Prolog is a good idea from a pragmatic standpoint; it may not be an impossible task, but I doubt if it is even worth doing it that way.

The inner part is where things start to get interesting. This is essentially a virtual machine which emulates the way a Prolog interpreter behaves. It is the central processing unit of the gameplay logic, which runs itself by executing rules which are written in declarative syntax (i.e. horn clauses).

The code below is a rough outline of what this "virtual Prolog machine" might look like if it were implemented inside a C# application.

public class VirtualPrologMachine

{

private int time = 0;

private const farthestLookbackTime = 1;

private HashSet<Fact> facts = new HashSet<Fact>();

private List<Rule> rules = new List<Rule>();

private List<Fact> factsTemp = new List<Fact>();

public void Init(HashSet<Fact> initialFacts, List<Rule> initialRules)

{

facts.Clear();

rules.Clear();

foreach (var fact in initialFacts)

facts.Add(fact);

foreach (var rule in initialRules)

rules.Add(rule);

}

public void Tick()

{

// Repeatedly scan the rules and evaluate them until we are unable to discover any more facts.

do

{

int numNewFactsDerived = 0;

// Look at the individual rules.

foreach (var rule in rules)

{

// For each rule, look at each one of its required conditions.

foreach (var condition in rule.Conditions)

{

// Look up the available facts and pattern-match each one of them with the given condition.

// Remember the matching sets of arguments (i.e. bindings).

foreach (var fact in facts)

{

...

}

...

}

// Derive new facts from sets of arguments (i.e. bindings) which satisfy ALL the conditions,

// Add these new facts to 'factsTemp'.

...

}

} while (numNewFactsDerived > 0);

// Add the new facts.

foreach (var fact in factsTemp)

facts.Add(fact);

factsTemp.Clear();

// Remove obsolete facts.

foreach (var fact in facts)

{

if (fact.Time < time - farthestLookbackTime)

factsTemp.Add(fact);

}

foreach (var fact in factsTemp)

facts.Remove(fact);

factsTemp.Clear();

// Increment the current time step.

time++;

}

}

public class Relation<T> where T : RelationArg

{

public string Name;

public int TimeOffset = -99; // -99 if the relation is timeless

public T[] Args;

public bool Negate;

}

public class Fact : Relation<T> where T : Constant

{

public int Time;

}The answer-finding procedure has not been fully specified here (They are left as: "..."), yet I believe that such details can be elaborated later on if necessary. Pieces of utility code which were introduced in Part 6 will probably be of help here.

Aside from the problem of figuring out all the valid bindings and converting them to facts, I would say that the overall goal of the "VirtualPrologMachine" class above is to serve as the central gameplay engine which is capable of evaluating the given set of rules and deriving new facts out of them whenever the "Tick()" method gets invoked.

Each call of the "Tick()" method represents a clock cycle (i.e. game loop). Every time it runs, it goes through all the given rules, identifies all the relevant facts as well as their appropriate bindings, and instantiates new facts (if applicable) out of such bindings. And in the end, it removes all the obsolete facts (i.e. ones that are too old) and increments the time step by 1.

The main problem is that the process of exhaustively finding all possible solutions (i.e. sets of bindings) to a Prolog query is so computationally expensive.

Each rule forces us to compare every one of its requisite conditions with every one of the applicable facts, which provides us with multiple alternative ways in which the condition's arguments could be bound. This means that the total number of pattern-matching steps involved in analyzing even a single rule can be quite colossal.

If the system were asked to process just a handful of rules based upon a modest number of given facts, it would have not been too much of an issue. But since a gameplay system usually involves an immeasurably huge number of facts and rules interacting with one other during every fraction of a second, we must start seriously considering the performance implication of the standard Prolog algorithm.

Fortunately, there are many ways in which a Prolog application could be optimized. One of the most obvious methods is to parallelize the means of rule evaluation. So, for example, if there are groups of rules in the system whose requisite relations (i.e. those on the right-hand side of the horn clause) do not depend on each other, we will be able to hand these groups over to separate threads and let them be handled concurrently. This way, we will be able to considerably reduce the amount of time being spent by the system to answer all the rules.

Another way, which may as well be employed jointly with the aforementioned solution, is to exploit some of the algorithmic shortcuts while analyzing the rules. This approach will require us to come up with slightly more advanced data structures, yet doing so will definitely be worthwhile.

You might have realized that one of the most significant sources of inefficiency in the code I have shown above is the way in which the facts are being stored. What I did was, I simply used a HaseSet (i.e. a hash table) to store all the available facts, without any means of organization whatsoever. Each time the system evaluates a relation, therefore, it is forced to go through all the entries of the set to be able to select the matching ones.

This is too wasteful, of course, and we should definitely introduce a bit of shortcuts to let the interpreter access the relevant entries more efficiently. For the sake of demonstration, I will begin with the simplest example.

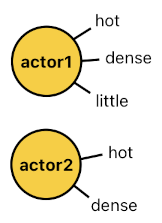

Let's say that the Prolog system is given the following list of facts:

FACTS:

hot(actor1).

dense(actor1).

little(actor1).

hot(actor2).

dense(actor2).

These are all unary facts, and they can be imagined as "tags" (i.e. adjectives) which are being attached to actors for the purpose of describing what they are. The constant "actor1", for example, can be depicted as "hot and dense and little" because it is associated with 3 tags: "hot", "dense", and "little". The constant "actor2", on the other hand, will be depicted as "hot and dense but not necessarily little" because it is associated with only 2 tags: "hot" and "dense".

Storing these facts is very straightforward. All we need to do is create a separate HashSet for each of the tags, so as to enable the interpreter to quickly access facts of the desired types (e.g. Whenever it wants to access facts which begin with the keyword "hot", it only needs to look up the entries in a set called "hot" and nowhere else).

The following code will show you how the aforementioned facts are able to be mapped into their corresponding HashSet entries.

public class Facts

{

public HashSet<string> hot;

public HashSet<string> dense;

public HashSet<string> little;

public void Init()

{

hot.Add("actor1");

dense.Add("actor1");

little.Add("actor1");

hot.Add("actor2");

dense.Add("actor2");

}

...

}So, here is the rule of thumb. Whenever you have a tag you want to attach to actors, create a HashSet to store all the actors which possess this tag. That's it! That's all you have to do.

All right, here is something more advanced.

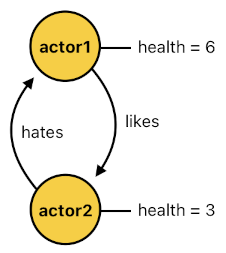

FACTS:

health(actor1, 6).

health(actor2, 3).

likes(actor1, actor2).

hates(actor2, actor1).

These ones involve multiple arguments, and they are somewhat more complicated than mere tags. The first two are numerical attributes, and they describe the actors' quantitative states. "health(actor1, 6)", for instance, represents the fact that the current health of "actor1" is 6.

The remaining two are relationships between actors which could be described in terms of simple keywords. "likes(actor1, actor2)", for instance, represents the fact that "actor1" likes "actor2". This kind of relation is binary in nature, since an actor either "likes" or "does not like" the other actor; there is no in-between (i.e. grayscale) state, as far as the semantic structure of "likes(X, Y)" goes.

Such facts can be accessed quite efficiently as long as we represent them as dictionaries (aka "HashMaps"), which are internally just hash tables. Each key of the dictonary will be the actor which is the "main subject" of the relation, and the key's corresponding value will be whatever thing that the subject is associated with in the context of the relation. The "likes" relation, for example, could be constructed as a dictionary in which each key indicates the subject who likes somebody else, and each value indicates that "somebody else" who is being liked by the subject.

public class Facts

{

public Dictionary<string, int> health;

public Dictionary<string, string> likes;

public Dictionary<string, string> hates;

public void Init()

{

health["actor1"] = 6;

health["actor2"] = 3;

likes["actor1"] = "actor2";

hates["actor2"] = "actor1";

}

...

}So yeah, the underlying idea is that we can simply use a dictionary (i.e. a bunch of key-value pairs) to store facts which describe relationships between things - that is, between the subjects (i.e. keys) and their associated objects (i.e. values).

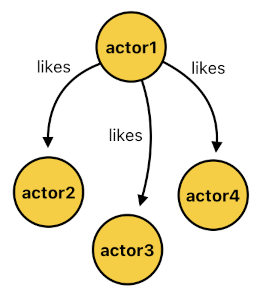

Oh, but here's the catch. What if a subject is involved in multiple relationships of the same type? For example, we could imagine a situation where "actor1" happens to like not only "actor2", but also "actor3" and "actor4" (See the list of facts below).

FACTS:

likes(actor1, actor2).

likes(actor1, actor3).

likes(actor1, actor4).

This problem is not hard to resolve at all. All we need is a dictionary whose values are sets of actors instead of just actors. This way, it will be possible to allow each key to reference multiple actors at once.

public class Facts

{

public Dictionary<string, HashSet<string>> likes;

public void Init()

{

likes["actor1"].Add("actor2");

likes["actor1"].Add("actor3");

likes["actor1"].Add("actor4");

}

...

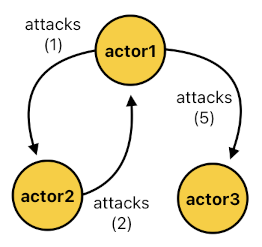

}Now, let me come up with relations which comprise more than two arguments. The following three facts (shown below) describe relationships between actors with their own numerical quantities. "attacks(actor1, actor2, 1)", for instance, implies that "actor1" is attacking "actor2" with the strength of 1.

FACTS:

attacks(actor1, actor2, 1).

attacks(actor1, actor3, 5).

attacks(actor2, actor1, 2).

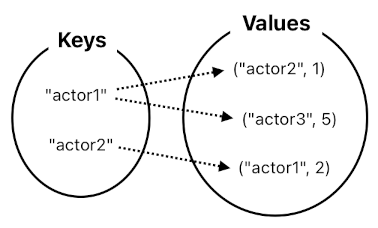

In each of these facts, the first argument indicates the subject who is attacking somebody else, the second argument indicates the object (i.e. target) who is being attacked, and the third argument indicates the strength of the attack. This means that, from the viewpoint of a dictionary, the first argument should be used as the key and the other 2 arguments should be used as its corresponding value. For convenience, let us just put these 2 arguments in a tuple and treat it as the data with which the key is associated. If we do so, the resulting data structure will look like this:

public class Facts

{

public Dictionary<string, HashSet<(string, int)>> attacks;

public void Init()

{

attacks["actor1"].Add(("actor2", 1));

attacks["actor1"].Add(("actor3", 5));

attacks["actor2"].Add(("actor1", 2));

}

...

}

Everything is the same as before, except that the set of values now consist of tuples instead of just singletons.

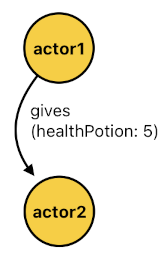

The idea of treating one of the arguments as the key and the rest as the value is pretty versatile, and is able to be extended as much as we desire. The act of handing over a certain number of items to another actor, for example, can be written as:

FACTS:

gives(actor1, actor2, healthPotion, 5).

This is a fact with 4 arguments, where the first two refer to the donor and receiver of the items, and the rest two refer to the type and number of items given. So in this case, the fact says that "actor1" is giving 5 bottles of health potion to "actor2".

Such a kind of relation can be constructed as a dictionary in which the set of values have 3-element tuples in them instead of 2, for the purpose of representing the receiver, the type, and the number of the items given.

public class Facts

{

public Dictionary<string, HashSet<(string, string, int)>> gives;

public void Init()

{

gives["actor1"].Add(("actor2", "healthPotion", 5));

}

...

}If the relation had 5 arguments in total, this tuple would have been 4 in length. If the relation had 6 arguments in total, this tuple would have been 5 in length, and so on. We just have to consider one of the arguments as the key, and the rest as parts of the value to which the key corresponds.

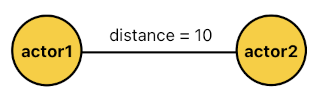

There are, however, cases in which treating only one of the arguments as the key may not be appropriate. If there is a relationship between two equally important subjects, for instance, we won't necessarily favor the notion of putting only one of them as the key of the dictionary and the other one as part of the mapped value. Here is a quick example which demonstrates such a scenario:

FACTS:

distance(actor1, actor2, 10).

The fact shown above tells us that the distance between "actor1" and "actor2" is 10. Here, should we say that "actor1" is the subject of this relation? Or should we say that "actor2" is the subject?

An honest answer would be that neither of them accurately reflects the symmetric nature of a distance. Both of the two given actors are of equal agency and, unlike in the previous examples, the "distance" relation does not suggest in any way that one of the actors is actively "doing something" against the other actor. In other words, "distance" is not a verb in which there is a clear distinction between the subject and the object.

In this case, therefore, it makes a lot more sense to consider both of the actors as the subject of the relation. It means that each key in the dictionary of "distance" relationships should be defined as the pair of actors involved.

public class Facts

{

public Dictionary<(string, string), float> distance;

public void Init()

{

distance[("actor1", "actor2")] = 10f;

}

...

}In general, though, choosing which arguments to use as the key of the dictionary can be quite tricky. It might appear as straightforward from a purely declarative standpoint, yet the problem is that we are also concerned about computational efficiency here.

When searching for facts of our interest, we want the lookup process to be as quick as possible. And in order to achieve this goal, we must try to minimize the number of dictionary lookups that the interpreter is required to perform when responding to a query.

In the next article, I will be talking about this aspect of database design, and how taking care of it will help us greatly improve the performance of the underlying system.

(Will be continued in Part 16)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service