Author: Youngjin Kang Date: August 25, 2024

As a fan of unconventional programming paradigms, I enjoy learning new programming languages which are drastically different from the typical object-oriented ones such as C#, Java, and the like. The most iconic of them are LISP (which is a powerful language for both functional programming as well as metalinguistic patterns in software development) and Prolog (which is one of the most popular languages in logic programming). Learning these languages is quite hard, compared to being acquainted with usual C-style imperative languages such as Ruby and Python, yet it has turned out to be one of the most effective ways of exercising one's brain.

By the time I started learning LISP via MIT's 1986 lecture series called "SICP (Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs)" back in 2018, I was already quite familiar with some of its core concepts (such as lambda expressions, higher-order functions, etc) because they were already integrated as some of the main features of C#, which was the language I was using all the time as a Unity game developer. Also, my academic background in electrical engineering (signal processing in particular) helped me easily grasp the idea of "stream processing" which appeared in the latter half of the lecture series. Thus, learning LISP and its functional design patterns was not as difficult as I imagined it to be.

A major intellectual challenge, however, struck me when I began to study Prolog - the famous logic programming language which is notorious for its esoteric syntax. The grammar itself did not appear to be complicated at all; it was just as minimal as that of LISP. The way in which programming had to be done in Prolog, though, was stressful enough to fry the engine of my brain. The way it approached data structures (such as lists) and algorithms based upon mathematical relations was something so revolutionarily novel to me, that it seriously opened up a new horizon in my faculty of computational reasoning.

While Prolog's approach in software development was quite alien to me, I managed to notice a number of familiar associations between Prolog and many useful topics in engineering. I discovered, for example, that the so-called "relational databases" (e.g. MySQL) are named so not because they comprise data tables which are related to each other via references, but because each row of a data table can be considered an n-ary predicate (where 'n' is the number of columns in the table) in Prolog's syntax. Besides, I found out that the input/output behavior of each digital circuit component (e.g. logic gate) could be implemented as an n-ary relation (where 'n' is the total number of the input/output ports combined), implying that an "object", whether it be a piece of hardware or a piece of pure data in memory, may as well be defined as a relation in logic programming (just like an object may as well be defined as a function in functional programming). Furthermore, the declarative nature of Prolog strongly convinced me that it must be optimal for data-driven design.

These realizations soon led me to contemplate upon the notion that, maybe, logic programming has a great deal of potential in the design and implementation of highly complex systems, such as a video game's core gameplay mechanics. I began to ask myself, "Will it be possible to develop an entire game using the grammar of logic programming?"

Indeed, there are reasons why most game developers just stick to general-purpose programming languages (such as C#) for making games, aside from purely experimental purposes. Implementing an entire game based on Prolog, for instance, is perhaps too much of a challenge for those who are not hardcore mathematicians. Also, Prolog may not be the best language to use for parts of the project which are not necessarily made of a complex web of relations, such as simple I/O modules, graphics modules, audio modules, physics modules, and the like.

However, I believe that at least the core mechanics of a game can definitely be implemented using the language of Prolog, and that we will be able to solve a plethora of complex design problems by doing so. It is because a gameplay system which is structured in terms of a set of declarative statements will be far more robust, modular, and free of confusing edge cases (e.g. race conditions) than an imperative system.

For this alternative methodology to be successful, one must start by designing the system in terms of logical relations/predicates only, and nothing else (That is, no functions, no structs, no classes, no interfaces, no state variables, etc). This will allow us to construct a gameplay system which is purely driven by the soul of Prolog.

The core idea in Prolog-based game programming is to utilize relations as the most primitive building blocks of the system, just like basic circuit components (e.g. resistors, transistors, capacitors, inductors, etc) are the most primitive building blocks of an electric circuit. It is sensible, therefore, to start this journey by considering the most rudimentary relations (e.g. unary and binary) first, and see if these elements can serve as the most essential nuts and bolts of the game.

Suppose that we are designing a game, and that the game consists of two major parts - world and actors (see the image above). The world is a scene in which everything is supposed to happen, and actors are objects which belong to the world. Examples of actors include "players", "enemies", "obstacles", "items", and pretty much any discrete entities which have their own names and attributes. Actors are able to interact with each other (as well as with themselves), from which various events occur. What we refer to as "gameplay" is a chain of such events.

We will begin formulating a gameplay system based off of this conceptual backbone. All you need to remember is that there is a world, and that the world contains a number of actors, each of which possesses its own state and behavior.

First of all, let us identify each individual actor with a unique name. If there are two actors in the world, for instance, we will simply assume that the name "actor1" and "actor2" will be used to indicate the first and second actors, respectively.

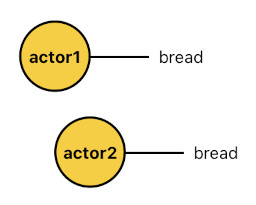

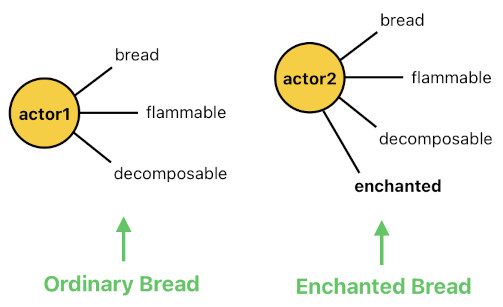

The first piece of logic I will illustrate is the idea of tags. A tag is a keyword which, when attached to an actor, describes what the actor stands for. When an actor has the tag "bread" attached to it, for example, we should be able to tell that the actor is a piece of bread.

The Prolog code below assigns the tag "bread" to both actor1 and actor2, in the form of unary predicates (The tag "bread" itself is an unary relation, and "bread(actor1)" & "bread(actor2)" are two separate instances of it). This implies that both actor1 and actor2 are pieces of bread.

bread(actor1).

bread(actor2).

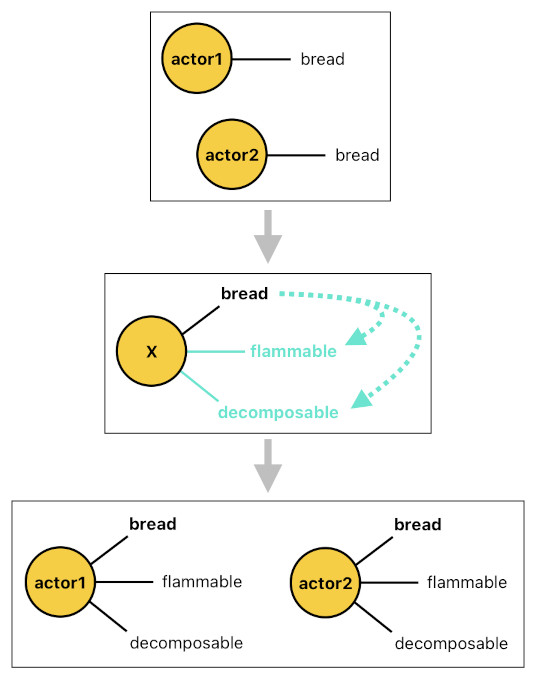

An actor can have multiple tags as well. However, one may feel that it is a bit too tedious to manually assign a bunch of tags to each individual actor. For example, let us say that every piece of bread must also be labeled as flammable and decomposable. This means that, whenever an actor is associated with the tag "bread", we are obliged to always ensure that it is also associated with the tag "flammable" and "decomposable". Manually attaching these two additional tags to every "bread" actor is way too cumbersome and error-prone. Fortunately, the following pair of horn clauses neatly solve this problem. They enforce the following two rules:

(1) Whenever tag "bread" is assigned to actor X, tag "flammable" will automatically be assigned to actor X.

(2) Whenever tag "bread" is assigned to actor X, tag "decomposable" will automatically be assigned to actor X.

flammable(X) :- bread(X).

decomposable(X) :- bread(X).

These horn clauses, therefore, serve as part of the game's "config data" - a list of data entries in the game's technical design document (like the ones you would see on a spreadsheet) telling us the characteristics of each individual character type, skill type, mission type, and so forth. The tags called "flammable" and "decomposable" in our case, for instance, are characteristics which belong to the type-specifier called "bread", meaning that any actor which can be identified as "bread" is a composition of two properties called "flammable" and "decomposable".

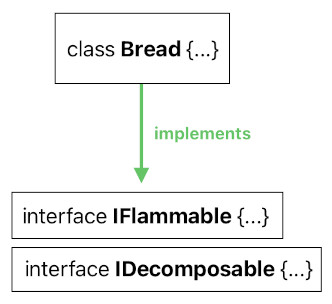

A decent analogy can be found in Unity game engine, where we may create a prefab called "Bread" with two components in it - "Flammable" and "Decomposable". Or, in a general object-oriented programming environment, "Bread" may stand for the name of a class which implements two interfaces called "IFlammable" and "IDecomposable".

In a way, therefore, horn clauses in Prolog play the role of data type definitions.

Aside from these pre-configured tags (which all rely on the presence of the tag "bread"), one may as well attach a custom tag to an actor as needed. For example, imagine that a wizard happened to enchant actor2 (i.e. the second piece of bread). This means that, unlike actor1 which is an ordinary piece of bread, actor2 must be an "enchanted" piece of bread which is required to have the tag "enchanted" attached to it for the purpose of showing us that it has been enchanted. The code below ensures that this is the case.

enchanted(actor2).

The tags "flammable" and "decomposable" are characteristics of all pieces of bread, whereas the tag "enchanted" is a characteristic of only special pieces of bread which have been enchanted by a wizard.

So far, we have been using tags for specifying the characteristics of each individual actor. In a gameplay system, however, we also need to specify relationships between actors, such as ways in which they interact, etc.

In an ecosystem, predators chase preys and preys run from predators. In a dating simulator, a guy tries to flirt with girls and girls reject him. In a social simulator (such as The Sims), people are either friends or enemies of each other, or somewhere in between. In the game of chess, a bishop devours a rook diagonally and a rook devours a bishop orthogonally. These are all relationships out of which the game's dynamics emerge.

Defining actor-to-actor relationships in Prolog is pretty straightforward. Just like an unary predicate can be used to characterize a single actor, a binary predicate can be used to characterize a relationship between a pair of actors. And by means of a horn clause, such a relationship can be dynamically deduced from a set of requisite conditions.

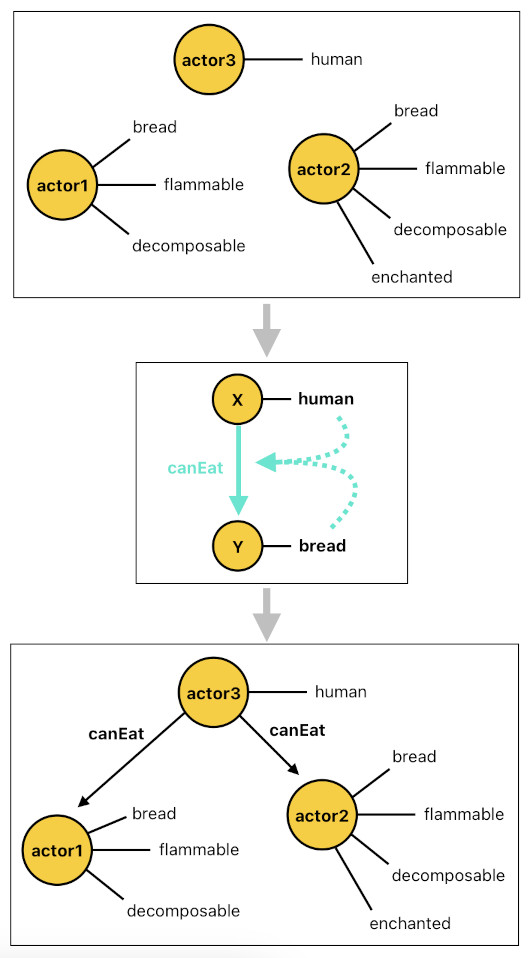

The following code is an example of a relationship. Suppose that there is a third actor called "actor3", and that we have declared it as a human (by attaching the tag "human" to it). Since a human is able to eat a piece of bread, we can confidently assert that "X can eat Y if X is a human and Y is a piece of bread". Here, "X can eat Y" is a relationship which holds whenever X is associated with tag "human" and Y is associated with tag "bread".

human(actor3).

canEat(X, Y) :- human(X), bread(Y).

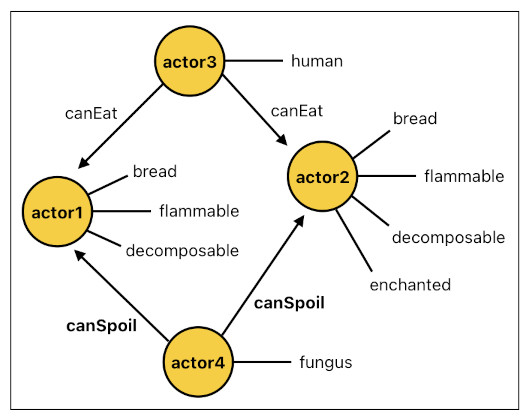

Here is another example. Since a piece of bread is decomposable (because anything which is identified as "bread" must also be identified as "decomposable"), we know that microbes such as fungi are capable of spoiling it. If there is an actor with the tag "fungus" attached to it, therefore, we will be able to tell that it must be able to spoil any other actor which is "decomposable". This is yet another case of a relationship between two types of actors; it is a relationship which says, "X can spoil Y if X is a fungus and Y is decomposable". The following code shows its definition.

fungus(actor4).

canSpoil(X, Y) :- fungus(X), decomposable(Y).

There is something still missing here, though. While I have demonstrated that it is possible to assign characteristics to individual actors as well as their mutual connections (i.e. relationships), I have not shown yet how to make these characteristics change over time. They all have been static so far, and the declarative nature of Prolog does not seem to offer an easy solution to make things dynamic.

If we want to create a game rather than a fixed landscape of how things are shaped permanently, we better let them move and interact as time goes by. In the next part of the series, I will explain how the game loop shall be conceptualized in Prolog.

(Will be continued in Part 2)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service