Author: Youngjin Kang Date: August 29, 2024

This is Part 2 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

So far, I have been demonstrating ways in which we can assign tags and relationships to each of the gameplay agents (aka "actors"). The key takeaway is to use predicates to specify them, as well as leverage the power of logical relations for letting the program automatically instantiate such predicates.

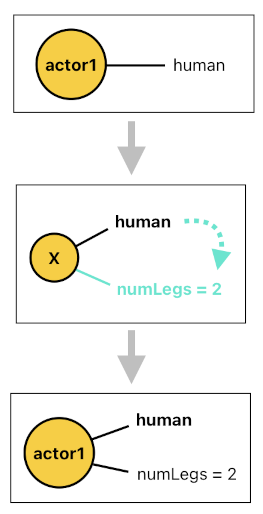

By the same spirit, we are also able to assign a numerical attribute to an actor. Suppose that an actor called "actor3" is tagged "human", and that we would like to ensure that every human actor has an attribute named "numLegs" which indicates the person's number of legs (i.e. 2). The following horn clause, then, will fulfill this objective.

numLegs(X, 2) :- human(X).

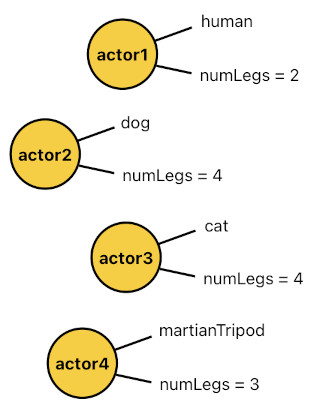

The binary predicate, "numLegs", is a numerical attribute of every human actor which tells us that the actor's number of legs is 2. This differs from a simple tag (i.e. keyword) in the sense that it also contains a number. This allows us to specify different "numLegs" values to different species of actors, like the ones shown below.

numLegs(X, 2) :- human(X).

numLegs(X, 4) :- dog(X).

numLegs(X, 4) :- cat(X).

numLegs(X, 3) :- martianTripod(X).

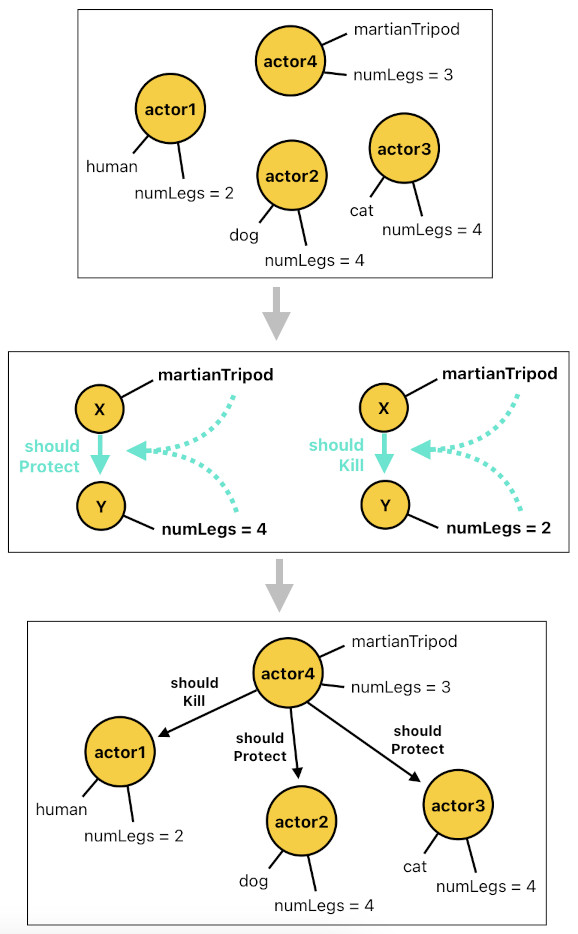

If every martian tripod were a faithful reader of George Orwell and happened to interpret every single phrase of his novel "Animal Farm" in the most blatantly literal manner, it would be reasonable to conclude that a martian tripod is likely to protect four-legged creatures and kill two-legged creatures ("Four Legs Good, Two Legs Bad"). These behavioral patterns can be implemented using horn clauses, which are illustrated below.

shouldProtect(X, Y) :- martianTripod(X), numLegs(Y, 4).

shouldKill(X, Y) :- martianTripod(X), numLegs(Y, 2).

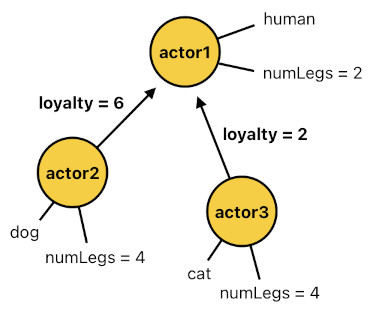

And of course, it is equally feasible to devise a numerical attribute which involves multiple actors, similar to the concept of relationship I have demonstrated before. For instance, imagine that a dog's degree of loyalty to a human being is 6, while a cat's degree of loyalty to a human being is only 2. These two numerical relationships can be modeled as two slightly different ternary relations, like the ones shown below.

loyalty(X, Y, 6) :- dog(X), human(Y).

loyalty(X, Y, 2) :- cat(X), human(Y).

This sort of reasoning can be expanded indefinitely. For example, one may as well define a numerical attribute which carries not just a single number, but multiple numbers (i.e. vector quantity). One may also define a relationship which involves not just two actors, but three or more actors, such as: "This girl hates her boyfriend for showing too much affection to the other girl", etc.

Things have been looking good so far. We know how to create attributes and relationships, as well as how to assign them to our gameplay agents, and so forth. However, we cannot make a game out of these building blocks alone.

What has been missing here is a sense of change over time. We want actors to move, interact, and make impacts upon the world as well as upon themselves. What we've got so far, instead, is a mere snapshot of how things are related to each other; there is no moving part at all.

So, how to turn this static world into something dynamic? First of all, let us recall the way in which an imperative programming language would approach this problem. In a typical imperative language such as C, C++, or Java, creating a sense of change is simple and straightforward.

Suppose that there is a clock which ticks at regular intervals. Every time it ticks, it calls a function called "Update". If there is an actor who is supposed to get hungrier and hungrier as time passes by, all we have to do in an imperative language is to access the actor's state variable called "hunger" and increase its value whenever the "Update" function runs (See the code below).

void Update(Actor x)

{

x.hunger = x.hunger + 1;

}This kind of logic is possible because the variable we are dealing with (i.e. hunger) is a state variable; we are allowed to assign a new value to it at any moment.

In a declarative language such as Prolog, unfortunately, we cannot just declare a state variable and modify its value whenever we want to. Logical relations are timeless beings; they exist outside of the realm of time, which means that it is nonsensical to try to associate them with variables which are bound to certain points in time.

What do we do, then? In order to mimic state transition in logic programming, we must approach the concept of time from a different angle. Rather than trying to directly manipulate the current state of the game while it is running, we ought to instead define a set of time-invariant statements which tell us how the past and present are related.

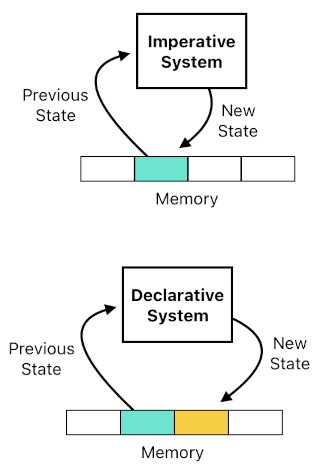

The figure above illustrates the core difference between the imperative and declarative means of running the game. Suppose that the game's state is being recorded in the computer's memory space (e.g. RAM), which is just an array of data slots.

In the imperative case, there is one chunk of data called "state". The game looks up this chunk of data, computes the new state, and overwrites this new state on top of the original chunk of data. This is what the assignment operator (i.e. "=") does in an imperative language.

In the declarative case, on the other hand, direct mutation of data is prohibited. At the beginning of each frame, the game first accesses the chunk of data at which the previous state was located. It computes the new state based on the previous state, and allocates this new state to a location which is currently not being used. The system does not tamper with the previous state; it simply appends the new state to the history of states without erasing or modifying the existing data.

The main advantage of this approach is that it gracefully prevents race conditions. Since it does not "change" any existing piece of data, it never has to worry about inadvertently disrupting another computational process which may have been accessing the same location in memory.

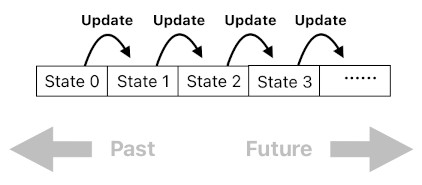

Of course, continually adding new copies of the game's state without deleting anything is too wasteful. Such an ever-growing list of states (which altogether constitute the game's "history"), unless the gameplay is either turn-based or very short in duration, is likely to eat up too much space in memory. This is clearly not desirable.

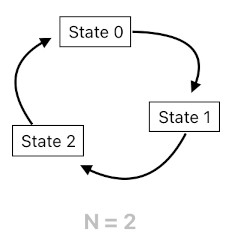

Such a problem, however, can easily be mitigated by limiting the maximum duration of time through which an event's effect is able to propagate. For example, if the game's current state is entirely determined by events which happened only up to N steps back in time, it will imply that the system only needs to retain the memory of N previous states (which corredpond to the N previous time steps) and nothing older than that. As you can see in the image below, this means that memory slots which are sufficiently old can simply be recycled for other purposes.

So, how do we implement such a declarative state transition mechanic in the language of Prolog?

Let us first examine how the functional paradigm would approach this problem. In functional programming (e.g. LISP), the game's "Update" function simply needs to take the previous state of the game as the input, instantiate the new state based off of the given previous state, and return this new state as the output. The returned output will then be appended to the game's state history as the most recent state, and the game loop (which is another function which is responsible for calling the "Update" function) will call the "Update" function once again, and again, and again, and so on, thereby periodically updating the game (For more details, please read: Functional Programming for Game Development).

In logic programming (e.g. Prolog), on the other hand, we cannot use such a functional methodology because functions are not a thing here. Instead, we must specify relations between the current and previous states, in a manner which resembles that of the so-called "difference equations" in mathematics.

In order to demonstrate how it works, let me first augment the syntax of Prolog a bit by introducing a number of additional symbols. These are not part of the standard Prolog (which means whichever Prolog interpreter you use won't be able to recognize them), so please keep that in mind. Any Prolog code you are going to see from now on should be taken as pseudocode, meant to serve as a mere proof of concept.

The snippet below is a list of notations which will be used to illustrate the game's temporal relations.

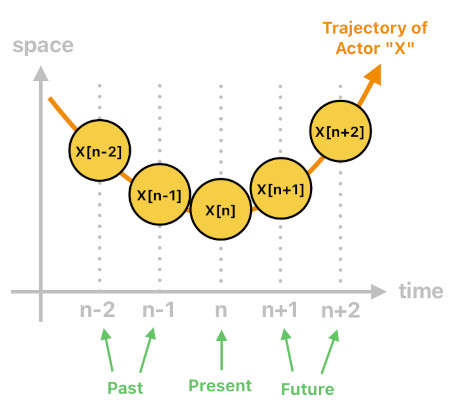

n = (current time step)

n-1 = (previous time step)

X[n] = (X at the current time step)

X[n-1] = (X at the previous time step)

X = (X at any time)Suppose that the game loop keeps track of time in discrete time steps, beginning with n = 0 and periodically incrementing it one by one (i.e. n = 1, n = 2, n = 3, etc). The symbol 'n' refers to the game's current time step, which means that 'n-1' refers to the previous time step, 'n-2' refers to the previous-previous time step (i.e. two steps back in time), and so on.

What's important here is the bracketed notation (e.g. "X[n]"). So far, I have only shown Prolog statements which involved timeless entities. Things like "actor1", "actor2", and "actor3", for instance, involved no concept of time whatsoever. Thus, there was no need to state their associations with respect to time.

When it comes to indicating an actor at a specific point in time, on the other hand, we can no longer just stick to a simple notation such as "X" because, if we do, we will be referring to the presence of the actor throughout the entirety of time. So in this case, we ought to attach an additional time parameter to the actor's identifier (e.g. "X[n]" for current X, "X[n-1]" for previous X, etc).

Before elaborating further, let me first introduce a couple of arithmetic relations which I will be using quite frequently from now on (See the snippet below). The "equal(...)" relation holds whenever its parameters are equal in value, meaning that "equal(3, 3)" and "equal(5, 5)" are TRUE, whereas "equal(1, 2)" and "equal(3, 5)" are FALSE. The "add(...)" relation holds whenever the sum of its first two parameters yields the value of its last parameter, meaning that "add(2, 2, 4)" and "add(3, 4, 7)" are TRUE, whereas "add(1, 2, 5)" and "add(4, 0, 6)" are FALSE. The "multiply(...)" relation works in a similar fashion.

equal(A, B) = (TRUE if A = B)

add(A, B, C) = (TRUE if A + B = C)

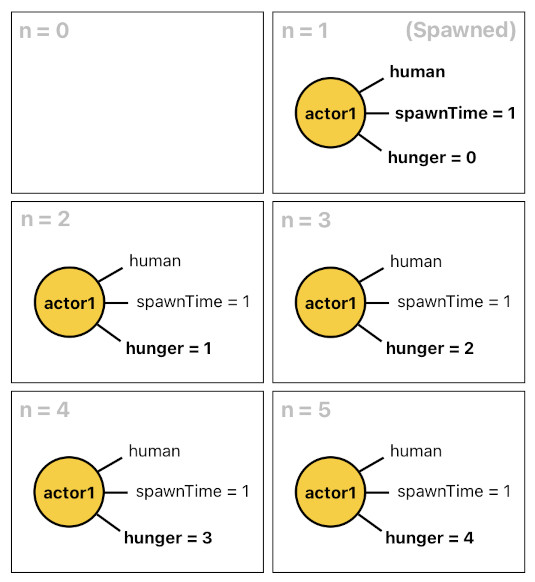

multiply(A, B, C) = (TRUE if AB = C)I will now explain how time-dependent relations can be used to implement gameplay dynamics. Imagine that there is an actor which is tagged as "human". Also, let us assume that this actor was spawned at some point in time. What we want here is to let this actor have its own state variable called "hunger", which starts at 0 (when the actor spawns) and increments itself by 1 every time the clock ticks.

The code below shows how it can be formulated in terms of executable rules.

hunger(X[n], 0) :- human(X[n]), spawnTime(X, n).

hunger(X[n], Curr) :- hunger(X[n-1], Prev), add(Prev, 1, Curr).

The first horn clause says that, if there is a human actor who just spawned right at the present moment (i.e. "n"), we must initialize its hunger to 0. This clause gets executed only once when the actor spawns, since it is the only moment at which "spawnTime(X, n)" can be evaluated as TRUE (Note: "spawnTime(X, n)" basically asks the question, "Is the current time the same as X's spawn time?").

The second horn clause says that, if there was an actor which had a state variable named "hunger" during the previous time step, its current hunger must be 1 greater than the previous hunger. This clause gets executed each time the clock ticks (i.e. whenever the time step increments by 1). It does NOT get executed during the moment at which the actor spawns, since "X[n-1]" is nonexistent during that time.

The first clause initializes the hunger, and the second clause periodically increments the hunger (because a human being is supposed to get hungrier and hungrier as time goes by).

But of course, the game will be pretty boring if all we can do is watch a human character starve. If we are to design a life simulator (like The Sims), for instance, there better be a way to quench the person's hunger by letting him/her eat some food.

Here is a bit of a trouble, though. We already have a rule which tells us that the hunger must increase by 1 each time the clock ticks. If we add a new rule which describes how much the hunger must go down when the actor eats food, this new rule will be incompatible with the existing one because it is logically contradictory to have two different horn clauses which are both trying to define the same piece of data (i.e. "X[n]") simultaneously.

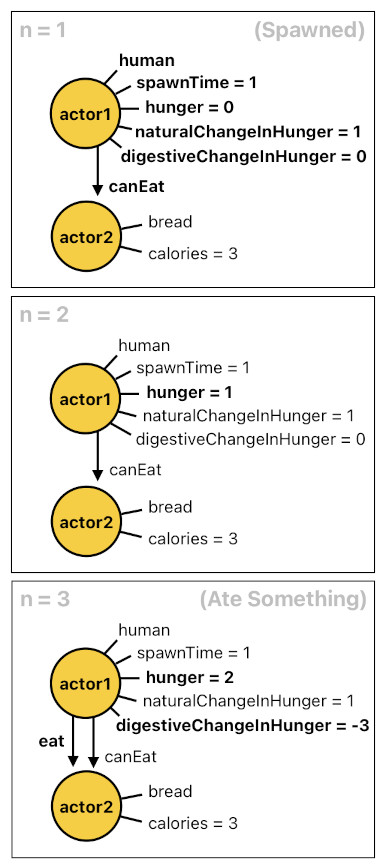

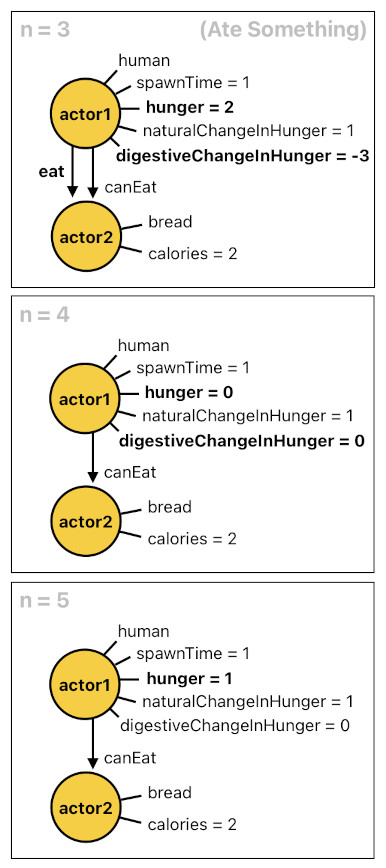

There is a pretty neat solution to this, fortunately. All we have to do is separately compute the amount of natural increment in hunger (aka "naturalChangeInHunger") and the amount of reduction in hunger due to the act of eating (aka "digestiveChangeInHunger"), and then combine them together into a single differential. Their implementations are shown below.

naturalChangeInHunger(X[n], 1) :- hunger(X[n], _).

digestiveChangeInHunger(X[n], ChangeInHunger) :- hunger(X[n], _), eat(X[n], Food[n]), calories(Food[n], NumCalories), multiply(NumCalories, -1, ChangeInHunger).

digestiveChangeInHunger(X[n], 0) :- hunger(X[n], _), !eat(X[n], Food[n]).

The first clause is easy to understand; it simply states that the natural change in hunger is always 1 (i.e. If the actor doesn't do anything, it naturally gets hungrier by the degree of 1 after each time step). The meaning of the second/third clauses is that, if an actor is currently eating some food, its hunger must be going down by the number of calories in the food (or 0 if the actor is not eating anything. This negatory relation is denoted by "!eat(...)").

One of the notable benefits of such mutually independent clauses is that they can run in parallel (by means of multi-threading or even GPU-based programs such as "compute shaders"). This provides us with yet another reason why logic programming is a great paradigm for gameplay engineering.

Anyways, once the application obtains the results of "naturalChangeInHunger" and "digestiveChangeInHunger", the only remaining step is to sum up these two results (which will be carried out by the predicate called "netChangeInHunger") and then add this sum to the actor's hunger, just as shown below.

netChangeInHunger(X[n], NetChange) :- naturalChangeInHunger(X[n], Change1), digestiveChangeInHunger(X[n], Change2), add(Change1, Change2, NetChange).

hunger(X[n], Curr) :- hunger(X[n-1], Prev), netChangeInHunger(X[n-1], NetChange), add(Prev, NetChange, Curr).

(Will be continued in Part 3)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service