Author: Youngjin Kang Date: September 19, 2024

This is Part 6 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

In Part 3, I mentioned that an event can be represented as a relation in the language of Prolog, as long as it belongs to a certain point in time. An event is usually a result of a set of preceding events (i.e. causes).

The time-related notations I have been using, though, may not reflect this underlying concept with a sufficient degree of accuracy. The main reason why this is so is that I have been attaching time parameters to the individual arguments of an event, rather than the event itself.

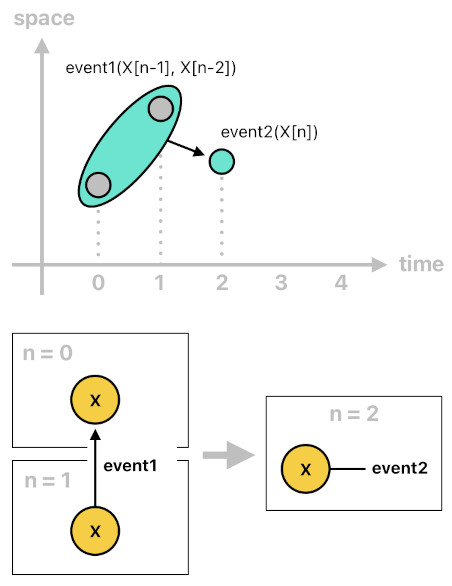

The example below is a simple instance of causation. In this case, the occurrence of "event1" during the previous time step (n-1) caused "event2" to happen during the current time step (n).

event2(X[n]) :- event1(X[n-1]).

Here is another example. In this case, we can still see that "event1" caused "event2" to happen. The time steps involved here are a bit different, though. What we see in this scenario is that "event1" is based not only on the state of X one step back in time (n-1), but also on the state of X two steps back in time (n-2). In other words, "event2" is caused by what happened at two distinct points in the past (n-1 and n-2).

event2(X[n]) :- event1(X[n-1], X[n-2]).

An event which belongs to multiple points in time, like the one shown above (i.e. "event1(X[n-1], X[n-2])"), is not logically absurd at all; such a kind of formulation makes perfect sense, both from pragmatic and theoretical points of view. However, it makes our representation of events a bit unnecessarily convoluted. And I say "unnecessarily" here because there really is no need for an event to stick itself to more than a single moment in time.

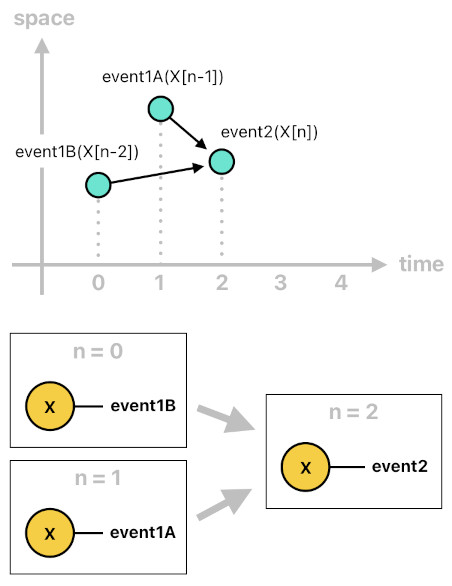

Let me ask you a question. Have we ever seen so far, from the very first part of this series, any Prolog code which demonstrated a relation with more than one time samples, such as "event1(X[n-1], X[n-2])"? The truth is that we have never seen one, and the reason is that it often makes a lot more sense to just break it down into two or more simpler events, just like the ones shown below (i.e. "event1A" and "event1B"). Think of these two events as the result of decomposing "event1" into two components (A and B).

event2(X[n]) :- event1A(X[n-1]), event1B(X[n-2]).

Let me show you a more specific example. Imagine that there is a guy (called "X") who is lost in the middle of wilderness. In order to notify his presence to the outside world, he decides to broadcast the word "SOS" using his telegraphic device, for the hope of being rescued by anyone who receives it.

The telegraphic communication protocol, however, only allows him to send one letter at a time, so he must transmit "s" first, wait for a moment, transmit "o", wait for another moment, and then finally transmit "s" to finish transmitting the word "SOS".

There are two alternative ways of implementing this.

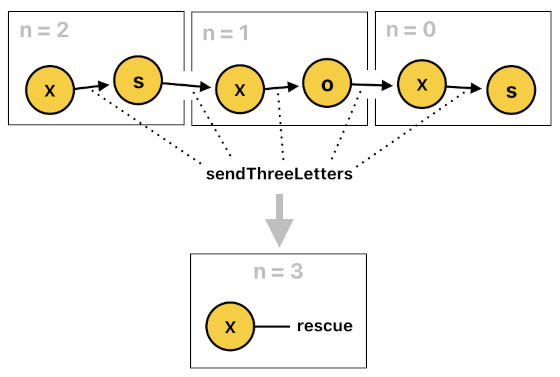

rescue(X[n]) :- sendThreeLetters(X[n-1], s[n-1], X[n-2], o[n-2], X[n-3], s[n-3]).

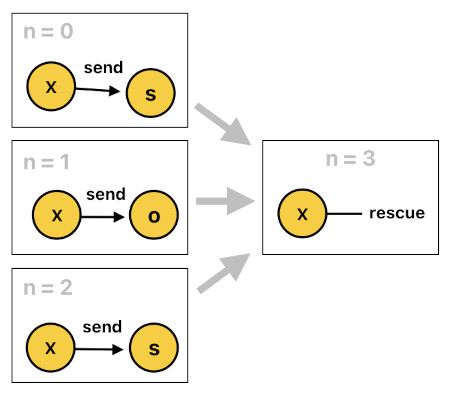

rescue(X[n]) :- send(X[n-1], s[n-1]), send(X[n-2], o[n-2]), send(X[n-3], s[n-3]).

In the first case, there is an event called "sendThreeLetters" which tells us that X has successfully sent the three letters (i.e. "s", "o", "s") during the last three time steps (i.e. n-1, n-2, n-3). When this event is detected, X gets rescued.

In the second case, there are three different "send" events. Each of these events represents the transmission of one of the three letters of the word "SOS". When all of these three events are detected, X gets rescued.

These two implementations are both valid, yet the second one is much more elegant because it ensures that each event is anchored to a single time step. This lets us associate each time parameter (such as "n-1") not with the event's individual arguments, but with the event itself. Thus, our horn clause can be re-written in a much simpler manner, like the one shown below:

rescue[n](X) :- send[n-1](X, s), send[n-2](X, o), send[n-3](X, s).In general, this new method of denoting time in Prolog applies to every case in which no event (i.e. relation) is bound to more than one moments in time. The rules of converting the old notations to their simplified equivalents are listed below.

r(X[n]) ---> r[n](X)

r(X[n], Y[n]) ---> r[n](X, Y)

r(X[n-1]) ---> r[n-1](X)

r(X[n-1], Y[n-1]) ---> r[n-1](X, Y)

r(X[n], Y[n-1]) ---> r1[n](X), r2[n-1](Y)

(... where "r = r1 AND r2")

r(X[n], Y) ---> r[n](X, Y)

r(X[n], n) ---> r[n](X, n)

r(X[n], n-1) ---> r[n](X, n-1)From now on, I will be using this new way of writing horn clauses.

There is another subtlety in Prolog-based game programming which I have not gone over yet; it is the problem of data types.

As you might have guessed already, I have been implicitly supposing the presence of a number of built-in data types when coding in Prolog. First of all, we all know that the language of Prolog consists of building blocks called "horn clauses", each of which is a mapping of multiple relations (i.e. conditions) into a single relation (i.e. result). Each relation may optionally have one or more arguments in it. The code below is a generic example of a horn clause:

relation3(arg3A, arg3B) :- relation1(arg1A, arg1B, arg1C), relation2(arg2A, arg2B).It is not hard to tell what horn clauses (aka "rules") and relations are, from a data abstraction point of view. If we are to embed the language of Prolog within a popular programming environment such as C#, we can easily define them as custom data types (i.e. classes or structs), like the ones shown below:

public class Rule

{

public Relation Result;

public Relation[] Conditions;

}

public class Relation

{

public string Name;

public int TimeOffset = -99; // -99 if the relation is timeless

public RelationArg[] Args;

public bool Negate;

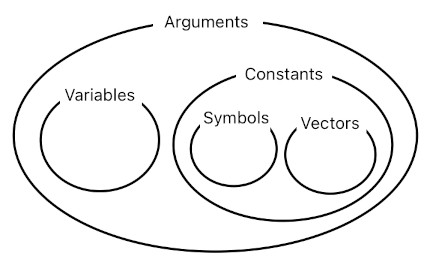

}When it comes to the individual arguments of a relation, however, a bit of ambiguity should creep in. To which data type does an argument belong? As keen readers may be able to tell already, there are multiple of them. The following types are the ones which I consider to be the most fundamental in my imaginary version of Prolog.

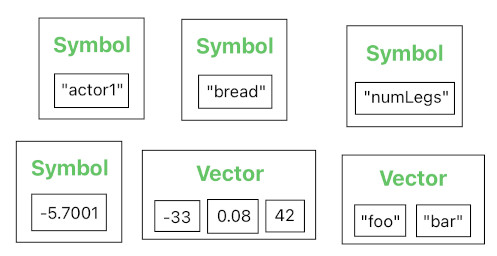

Variables:

Foo, X, Num, W3, Pos_1, Y, Value, NextVal52-0

Symbols (Constants):

foo, 123hello, x_3, 5, -42, 0.8, 1/3, 2.0/3.47

Vectors (Constants):

<3, 6.75>,

<value3, y, z1>,

<x, -95>

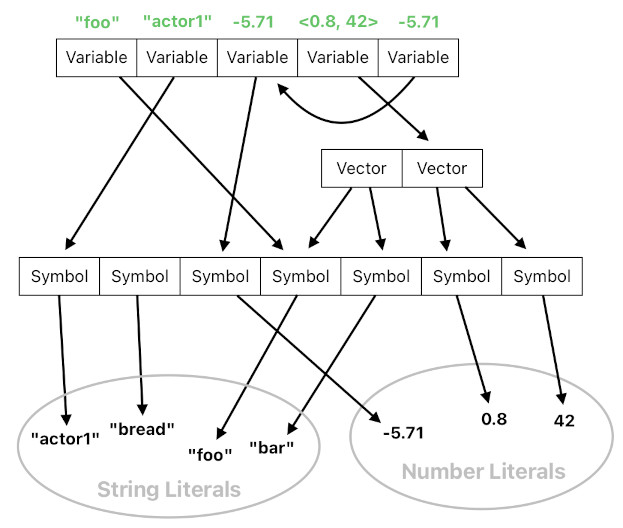

An argument whose name begins with an uppercase letter denotes a variable. A variable is basically a reference; it is an indicative entity which points itself to a constant value.

An argument whose name does NOT begin with an uppercase letter, on the other hand, denotes a constant. It is a specific piece of information, stored somewhere in the computer's memory. The question is, "What kind of information?"

If we were dealing with a "pure" version of Prolog, intended to be used solely for academic purposes, I would say that only the atomic ones (i.e. symbols) must qualify as part of the language's dictionary of build-in data types. A pristine system of logic, which is supposed to be devoid of any superfluous posture of complexity, would probably be obliged to exclude non-atomic data types (such as List, Set, Map, Graph, etc) from its ground-level semantics.

For the sake of convenience and efficiency, however, it is sometimes necessary to break free from such a harsh constraint unless we are conducting a purely theoretical research (e.g. proving a theorem in mathematics, etc). Since the topic of this article is game programming, it will be helpful if we just "extend" the language of Prolog a bit to bypass a myriad of potential challenges.

Now you may understand why I listed "Vector" as one of the built-in types. A vector is not necessarily an innate part of the original Prolog, but its addition nicely solves a great deal of trouble in the context of general-purpose computing.

Being able to put an arbitrary number of things together (i.e. vector) is an indispensable feature to have in a programming language. Thus, why not just let us assume that we are using a special Prolog interpreter which is designed to support this by default?

One might argue that introducing Vector as a built-in type should be considered a source of innumerable pitfalls, due to the possibility of forming weird nested structures such as a variable inside a vector, a vector inside a vector, and so forth.

Such a concern, however, is not going to matter if we enforce the rule that a Prolog vector must only permit symbols (atomic constants) as its components. This means that, for the sake of simplicity, there should not be any inner variables or inner vectors inside a vector.

The benefit of this constraint is that it allows vectors to be treated as literal values (similar to string literals), which then won't demand any special treatment at all. Each of them will simply be understood as a result of concatenating multiple symbols together in the form of an array. And whenever the Prolog application wants to bind a variable to a vector, all it needs to do is let that variable point to the vector's location in memory and regard it as a "compound symbol" - a symbol which is made out of more elementary (primitive) symbols, just like a molecule is made out of atoms.

And whenever the program is to perform a pattern-match between two constants (to see if a predicate evaluates to TRUE), all it needs to do is apply one of the two different protocols depending on their type. If they both belong to the type "Symbol", a simple equality check (=) will suffice. If they both belong to the type "Vector", their equality check will be carried out in a pairwise manner (i.e. compare the first elements, compare the second elements, and so on).

The code below is a rough draft of how the matching of relations and their arguments may be done in a C# implementation of Prolog, based on the data types I have mentioned so far.

public abstract class RelationArg

{

}

public class Variable : RelationArg

{

public string Name;

}

public abstract class Constant : RelationArg

{

}

public class Symbol : Constant

{

public string Value;

}

public class Vector : Constant

{

public Symbol[] Components;

}

public class VariableBinding

{

public VariableBinding Prev;

public string VariableName;

public RelationArg BoundArg;

}

public static class RelationUtil

{

public static VariableBinding MatchRelations(Relation r1, Relation r2, VariableBinding newestBinding)

{

if (r1.Name != r2.Name)

return null;

int size1 = r1.Args.Length;

int size2 = r2.Args.Length;

if (size1 != size2)

return null;

for (int i = 0; i < size1; ++i)

{

VariableBinding newBinding = MatchRelationArgs(r1.Args[i], r2.Args[i], newestBinding);

if (newBinding != null)

newestBinding = newBinding;

else

return null;

}

return newestBinding;

}

public static VariableBinding MatchRelationArgs(RelationArg arg1, RelationArg arg2, VariableBinding newestBinding)

{

if (arg1 == null || arg2 == null)

{

return null;

}

if (arg1 is Symbol s1 && arg2 is Symbol s2)

{

return (s1.Value == s2.Value) ? newestBinding : null;

}

else if (arg1 is Vector v1 && arg2 is Vector v2)

{

int size1 = v1.Components.Length;

int size2 = v2.Components.Length;

if (size1 != size2)

return null;

for (int i = 0; i < size1; ++i)

{

if (v1.Components[i].Value != v2.Components[i].Value)

return null;

}

return newestBinding;

}

else if (arg1 is Variable var1 && arg2 is Variable var2)

{

if (var1.Name == var2.Name)

return newestBinding;

RelationArg found1 = FindBinding(var1.Name, newestBinding);

RelationArg found2 = FindBinding(var2.Name, newestBinding);

if (found1 != null && found2 != null)

{

return MatchRelationArgs(

(found1 != null) ? found1 : var1,

(found2 != null) ? found2 : var2,

newestBinding);

}

else

{

newestBinding = AddBinding(var1.Name, (found2 != null) ? found2 : var2, newestBinding);

newestBinding = AddBinding(var2.Name, (found1 != null) ? found1 : var1, newestBinding);

return newestBinding;

}

}

else if (arg1 is Variable va1 && arg2 is Constant co2)

{

return MatchVarAndConst(va1, co2, newestBinding);

}

else if (arg1 is Constant co1 && arg2 is Constant va2)

{

return MatchVarAndConst(va2, co1, newestBinding);

}

else

{

return null;

}

}

public static RelationArg FindBinding(string variableName, VariableBinding newestBinding)

{

if (newestBinding.VariableName == variableName)

return newestBinding.BoundArg;

else

return newestBinding.Prev != null ? FindBinding(variableName, newestBinding.Prev) : null;

}

public static VariableBinding AddBinding(string variableName, RelationArg argToBind, VariableBinding prevBinding)

{

VariableBinding newBinding = new VariableBinding();

newBinding.Prev = prevBinding;

newBinding.VariableName = variableName;

newBinding.BoundArg = argToBind;

return newBinding;

}

public static VariableBinding MatchVarAndConst(Variable variable, Constant constant, VariableBinding newestBinding)

{

RelationArg found = FindBinding(variable.Name, newestBinding);

if (found != null)

return MatchRelationArgs(found, constant, newestBinding);

else

return AddBinding(variable.Name, constant, newestBinding);

}

}(Will be continued in Part 7)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service