Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 24, 2024

This is Part 17 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

At this point, you might be wondering, "Okay, what's with all this talk about HashSets and Dictionaries? Aren't you trying to come up with a Prolog-based game development framework? Why are you using C# data structures to explain your Prolog code?"

Let me tell you a reason why I have been taking such a route when illustrating the concepts.

First of all, the underlying assumption is that a Prolog-based game is not necessarily built entirely out of Prolog's logic programming system alone. A game is inexplicably broad in scope when it comes to software architecture; its development strategy oftentimes demands the aid of multiple programming paradigms, including not just logic programming, but also functional programming, object-oriented programming, etc.

Because of that, it is far more desirable to construct a specialized Prolog system inside the overall game project and make it be responsible for just the core gameplay logic and nothing else, rather than forcing ourselves to code the entire application in Prolog and letting the standard Prolog interpreter to run the whole thing. Such a methodology will be terribly inefficient, both performance and development-wise.

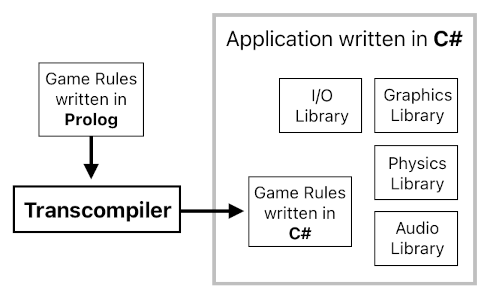

This is the main reason why I have been showing C# code to explain the inner workings of our custom Prolog engine. Eventually, it is not going to be the Prolog script itself which will be executed directly by the program. There will be some kind of "Prolog transcompiler" which will translate our (pseudo) Prolog code into a more machine-friendly language, such as C/C++, C#, Java, etc, so that embedding it within the project's general programming environment (e.g. .NET, Unity, or whatever) will be as swift as putting chocolate syrup on top of chocolate ice cream.

Code which is written in Prolog, by default, is not necessarily the most efficient thing to run for most computers (Most contemporary computing devices are optimized to run machine-level instructions, which are imperative in nature and thus show direct correspondence to Assembly, C, and other procedural programming languages). Therefore, it does not make much sense to execute a Prolog-based application on a PC and expect it to do its job well.

A custom transcompiler can come to our rescue for this reason. When crafting the core gameplay logic, we can simply write most of the mechanics in Prolog in order to keep the code clean. And then, we should be able to feed this code into the transcompiler to convert it into its imperative equivalent (e.g. C#), so that the resulting source code will be easily compiled (along with the rest of the project's codebase) into a list of highly optimized binary instructions.

Here's how it could be done. For the sake of demonstration, I will suppose that the goal is to translate Prolog into executable C# code.

The very first step of our hypothetical transcompiler is to take the Prolog script, read its lines one by one, and turn each of them into a piece of C# code which can be placed alongside other generated pieces (e.g. a class, a function, or an entry in a data structure). The question is, what kind of code would that be?

As you may have realized, the C# examples I showcased in the previous few articles were more or less pseudo code. However, they still reflect the general spirit of cross-language development pretty well, and only demand a little bit of adjustment to make everything come together and fit nicely as a whole, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

The following Prolog script is just an arbitrary example I wrote from scratch. It consists of two sections - facts and rules. The former denotes a bunch of initial facts which will be given to the world by the time the game begins (You can tell it quite clearly, since they all belong to time 0). The latter, on the other hand, gives us ways of deriving new facts out of the given ones.

% INITIAL FACTS

bar1[0]("hello", 30).

bar1[0]("hello", 40).

bar1[0]("world", 8).

bar2[0](<42, -550>, 999, "something").

bar3[0](72).

% RULES

foo1[n](X, Y) :- bar1[n]([key]X, Z), bar2[n-1](Y, [key]Z, W).

foo2[n](X) :- bar3[n-1](Y), bar1[n-1](X, [key]Y).What the Prolog transcompiler will need to do when converting this script into its C# equivalent, therefore, will consist of two major steps.

The first step, which I will be describing shortly, is to write a C# class which initializes data structures that are responsible for storing all the facts. Such facts are either initially provided (by the script's initial list of facts at time 0) or are able to be inferred via the rules as time passes by. Upon instantiation, these structures will be stuffed with all the initial facts which must be available when the game starts.

The second step is to write the individual rules as custom C# classes, with custom methods for evaluating them in their own unique ways. The central engine of our Prolog system, then, will iterate the instances of these classes and run their evaluation methods during every game loop, thus simulating the real-time rule evaluation logic.

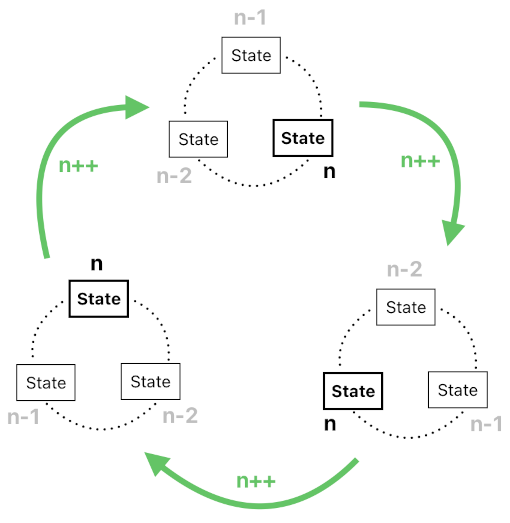

Let me begin with the first step - the initialization of data structures which will be storing facts. The following code is our hypothetical result of transcompiling the "initial facts" section of the above Prolog script into an equivalent C# class. It is called "State", and its job is to store facts which belong to a certain point in time. This means that, if the game needs to remember the history of its own state for 3 consecutive time steps (e.g. from "n-2" to "n"), it will need to create 3 instances of the "State" class and update them in a cyclic manner (which will let us simulate the "window of remembrance" which shifts itself over time - see the last few paragraphs of the "Causality" section in Part 3 for details).

public class State

{

public Dictionary<string, HashSet<int>> bar1_byX = new();

public Dictionary<int, HashSet<string>> bar1_byY = new();

public Dictionary<int, HashSet<((int, int), string)>> bar2 = new();

public HashSet<int> bar3 = new();

public Dictionary<string, HashSet<(int, int)>> foo1 = new();

public HashSet<string> foo2 = new();

public State(int n)

{

if (n == 0)

{

bar1_byX["hello"] = new(){ 30, 40 };

bar1_byX["world"] = new(){ 8 };

bar1_byY[30] = new(){ "hello" };

bar1_byY[40] = new(){ "hello" };

bar1_byY[8] = new(){ "world" };

bar2[999] = new(){ ((42, -550), "something") };

bar3.Add(72);

}

}

public void Clear()

{

bar1_byX.Clear();

bar1_byY.Clear();

bar2.Clear();

bar3.Clear();

foo1.Clear();

foo2.Clear();

}

}

As you can see, all current and future facts which have been mentioned in the Prolog code (i.e. bar1, bar2, bar3, foo1, and foo2) have their corresponding storage spaces in the form of either Dictionaries or HashSets. Adding and removing facts will be nothing more than adding and removing data entries to/from these custom structures, which are basically just hash tables from a computational point of view.

The underlying assumption here is that our "Prolog transcompiler" will parse the developer's Prolog script, read all types of facts which have been mentioned inside the script, infer their arguments' data types from the way in which their literal values are being specified in the initial list of facts (e.g. "bar3" is a set of integer values because "bar3[0](72)" suggests that bar3's argument is supposed to indicate a numerical quantity, etc), and create the appropriate data storages for them.

One noteworthy thing here is that any fact of type "bar1" must be stored in both "bar1_byX" and "bar1_byY" simultaneously, where the former one maps the first argument to the second, while the latter one maps the second argument to the first. The reason why the transcompiler is supposed to do this is that the "bar1" relation is required to be able to utilize both of its two arguments as keys.

In the first rule, the key specifier in "bar1[n]([key]X, Z)" orders the system to use bar1's first argument as the key when looking up the value of the second argument. In the second rule, in contrast, the key specifier in "bar1[n-1](X, [key]Y)" orders the system to use bar1's second argument as the key when looking up the value of the first argument. Therefore, the transcompiler must be able to recognize the bidirectionality of bar1's lookup pattern and come up with two different dictionaries for the sake of search efficiency.

After initializing the facts and their appropriate data structures, the transcompiler will then proceed to make custom C# classes for all the rules listed in the Prolog script.

In our example, there are only two rules - the one for deriving facts of type "foo1", and the other one for deriving facts of type "foo2". Thus, it makes sense to imagine that the parsing algorithm will create two distinct rule classes (i.e. "Rule_foo1", "Rule_foo2") and provide them with their means of evaluation. The generated C# code will look something like the one shown below.

public abstract class Rule

{

public abstract int Evaluate(int n, State[] states);

}

public class Rule_foo1 : Rule

{

public override int Evaluate(int n, State[] states)

{

int numNewFactsDerived = 0;

State currState = states[n % states.Length];

State prevState = states[(n-1) % states.Length];

foreach (var kvp1 in currState.bar1_byX)

{

var X = kvp1.Key;

var Z = kvp1.Value;

foreach (var kvp2 in prevState.bar2[Z])

{

var Y = kvp2.Value.Item1;

var W = kvp2.Value.Item2;

if (X == Y)

{

if (!currState.foo1.ContainsKey(X))

currState.foo1[X] = new();

if (!currState.foo1[X].Contains(Y))

{

currState.foo1[X].Add(Y);

numNewFactsDerived++;

}

}

}

}

return numNewFactsDerived;

}

}

public class Rule_foo2 : Rule

{

public override int Evaluate(int n, State[] states)

{

int numNewFactsDerived = 0;

State currState = states[n % states.Length];

State prevState = states[(n-1) % states.Length];

foreach (var Y in prevState.bar3)

{

foreach (var kvp1 in prevState.bar1_byY[Y])

{

var X = kvp1.Value;

if (!currState.foo2.Contains(X))

{

currState.foo2.Add(X);

numNewFactsDerived++;

}

}

}

return numNewFactsDerived;

}

}Here, each rule has its own C# class. It has a method called "Evaluate()" which, when called, looks up all the relevant facts, evaluates the conditions, and creates/stores a new fact if all of them are satisfied.

Each of these Rule classes runs its own nested for-loops when asked to evaluate itself, going over all possible combinations of arguments which may result in the discovery of new facts. Derived facts get added immediately to the current state object (i.e. instance of the aforementioned State class which belongs to the current time step), thereby allowing other rules to access them thereafter.

For the sake of thorough demonstration, I will introduce yet another rule (called "foo3") which contains a bit of slightly more advanced syntax - negation (denoted by "!") and pattern-matching of vector quantities. It is shown below.

foo3[n](G) :- bar1[n](X, G), !foo1[n-1](X, <G, 33>).Comparing vector quantities is not that complicated. You just compare each of its elements with its specified value, and then check to see if all these comparisons return TRUE when evaluated. In our example, the first component of <G, 33> turns out to be the variable "G" and the second component turns out to be the constant "33", so the resulting conditional statement will be a logical AND (&&) between "G == [first component of <G, 33>]" and "33 == [second component of <G, 33>]".

Handling negation is trickier, but it is not rocket science either. Instead of just iterating all the entries and picking up the pattern-matching ones, the algorithm simply needs to check if ANY of these entries pattern-match at all. If none of them does, then boom! We just found a new fact.

The following code is the precise implementation of what I just described.

public class Rule_foo3 : Rule

{

public override int Evaluate(int n, State[] states)

{

int numNewFactsDerived = 0;

State currState = states[n % states.Length];

State prevState = states[(n-1) % states.Length];

foreach (var kvp1 in currState.bar1_byX)

{

var X = kvp1.Key;

var G = kvp1.Value;

bool matchFound = false;

foreach (var kvp2 in prevState.foo1[X])

{

if (G == kvp2.Value.Item1 && 33 == kvp2.Value.Item2)

{

matchFound = true;

break;

}

}

if (!matchFound)

{

if (!currState.foo3.Contains(G))

{

currState.foo3.Add(G);

numNewFactsDerived++;

}

}

}

return numNewFactsDerived;

}

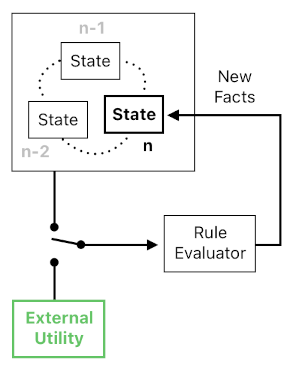

}Prolog code is made up of rules, and each rule is made up of a series of relations which must be satisfied in order to infer a fact out of it. In the previous section, I treated all the relations as though they are based upon whichever facts that are currently available. This made the resulting C# code simply look up the fact-storing data structures (i.e. HashSets and Dictionaries) to evaluate these relations.

There have also been, however, certain types of "utility relations" which were meant to perform mathematical operations such as simple arithmetics (e.g. addition, substraction, etc).

add(X, Y, Z)

subtract(X, Y, Z)

greaterThan(X, Y)

lessThan(X, Y)It is obviously impractical to try to find answers to such relations by referring to a lookup table and trying out all possible combinations of inputs to see which of them happens to match their desired output. Therefore, it makes much more sense to let the transcompiler override their default pattern-matching algorithm (i.e. dictionary lookups, etc) with functions which are built-in somewhere else in the C# codebase.

So, for instance, we may consider classifying Prolog's utility relations into their appropriate categories, like the ones shown below.

MATH::add(X, Y, Z)

MATH::subtract(X, Y, Z)

LOGIC::greaterThan(X, Y)

LOGIC::lessThan(X, Y)Relations which belong to such categories, then, will be interpreted by the transcompiler as ones whose arguments must be evaluated by invoking static utility functions which have been written separately from the process of transpilation itself (See the code below).

public static class MATH

{

public static bool add_XYZ(int X, int Y, int Z) // All 3 arguments are given

{

return X + Y == Z;

}

public static int add_XY(int X, int Y) // Both inputs are given but not the output (Returns the value of Z)

{

return X + Y;

}

public static int add_XZ(int X, int Z) // First input and the output are given (Returns the value of Y)

{

return Z - X;

}

public static int add_YZ(int Y, int Z) // Second input and the output are given (Returns the value of X)

{

return Z - Y;

}

...

}

public static class LOGIC

{

...

}For example, suppose that we've got another rule in the Prolog script called "foo4", which utilizes the process of addition like this:

foo4[n](H) :- bar1[n](X, G), MATH::add(G, 2, H).This rule should then be transformed into a class whose method of evaluation directly calls a utility function (called "add_XY()") in the "MATH" class which had been pre-written outside of the transcompiler-generated source code. The "Rule_foo4" class below demonstrates how this type of reasoning would work.

public class Rule_foo4 : Rule

{

public override int Evaluate(int n, State[] states)

{

int numNewFactsDerived = 0;

State currState = states[n % states.Length];

State prevState = states[(n-1) % states.Length];

foreach (var kvp1 in currState.bar1_byX)

{

var X = kvp1.Key;

var G = kvp1.Value;

var H = MATH.add_XY(G, 2);

if (!currState.foo4.Contains(H))

{

currState.foo4.Add(H);

numNewFactsDerived++;

}

}

return numNewFactsDerived;

}

}Overall, the Prolog transcompiler does many things. It creates data structures for storing facts, as well as initially filling them up with facts which are initially given. It also creates custom Rule classes that are equipped with their own methods of evaluation, which involve either: (1) pattern-matching of relations with their relevant facts, or (2) direct invocation of utility functions.

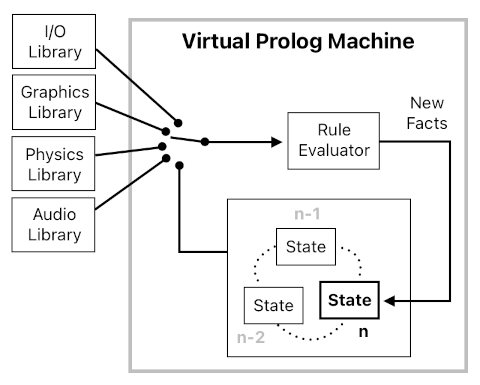

All these specialized modules, however, won't be of use unless there be a central place in which they can come together and collaborate as a whole. And that is exactly what our transcompiler should be writing in its final stage of script interpretation; eventually, it will produce a singleton class which will be responsible for executing the overall Prolog-based gameplay logic system (namely, "VirtualPrologMachine"). The implementation of such a class is displayed below.

public class VirtualPrologMachine

{

private int n;

private State[] states;

private Rule[] rules;

public VirtualPrologMachine()

{

states = new() {

new State(0),

new State(-1),

...

};

rules = new() {

new Rule_foo1(),

new Rule_foo2(),

new Rule_foo3(),

...

};

}

public void Update()

{

int currStateIndex = n % states.Length;

// Delete facts that are too old.

states[currStateIndex].Clear();

// Evaluate the rules until no more new facts can be derived.

int numNewFactsDerived = 0;

int trial = 0;

do

{

foreach (var rule in rules)

{

numNewFactsDerived += rule.Evaluate(n, states);

}

} while (++trial > 3 || numNewFactsDerived == 0);

n++;

}

}

The "states" array represents the most recent history of the game's state, which covers the present moment and stretches all the way back to the most distant past which will ever be referenced by the game's rules. The "rules" array is just the list of all the rules (i.e. horn clauses) which were written in the original Prolog script, and "n" is the current time step.

The "Update()" method is what runs the game. Whenever it is called, it: (1) erases facts that are too old, (2) evalutes all the given rules, (3) infers new facts out of them, and (4) increments the current time step.

Calling this method over and over again, therefore, will basically repeat these steps in a cyclic fashion, thereby progressing the game forward by continuously generating new facts out of what happened during the recent past.

(Will be continued in Part 18)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service