Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 24, 2024

This is Part 18 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

Quite frankly, though, I should admit that running all the rules on a single thread may significantly hurt the performance of the system, especially if the total number of rules is not so small. A typical rule tends to involve nested for-loops. And, while these loops can be optimized pretty well under careful algorithmic choices, the cumulative sum of the work involved may be detrimental to the game's average framerate.

Fortunately, we know that most of the rules are parallelizable; they are able to be evaluated concurrently without necessarily relying on each other's results. And even if they do, we can resolve such issues of dependency by running the same list of rules multiple times during each time step. This will hurt the performance a bit, of course, but the good news is that it enables us to save a lot more bandwidth in exchange by letting things run in parallel.

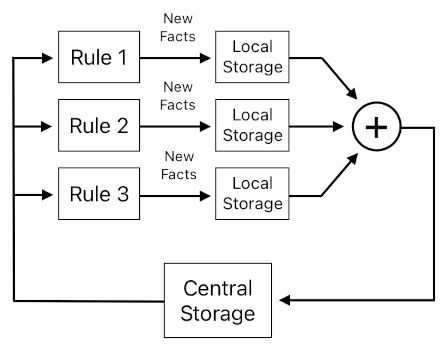

Here is how we are going to do it. Rules are encapsulated in their own class instances, so they are already pretty modular in nature. Their only place of mutual interference is the instance of the State class which belongs to the current time step (namely, "currState"), so the only major adjustment we ought to make is to let the individual rules temporarily keep their newly derived facts in their own local spaces, instead of directly committing them to the shared state object during the "Evaluate(...)" method call.

Once the concurrent evaluation of the rules is over, the central system can then gather all the new facts which were generated by the rules, and put them all into the current state of the game before starting the next cycle of rule evaluation. That way, individual rules will be free to evaluate themselves in parallel without interfering with one another. The diagram below will show you in detail how this concept works.

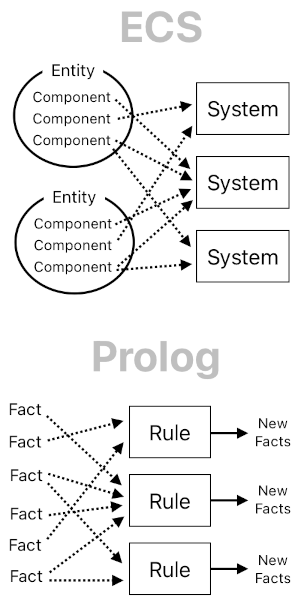

This Prolog-based gameplay design technique, by the way, may feel already familiar to you. In my opinion, it shares the same spirit with that of the ECS (Entity Component System) framework which used to be (and perhaps still is) one of the hottest areas of research amongst the developers of Unity game engine (namely, Unity DOTS & Unity ECS).

The so-called "systems" in ECS can be interpreted as rules (i.e. horn clauses) in the language of Prolog, since they are the ones responsible for updating the game's state by looking at existing entities and generating new ones based off of them. Entities and their components in ECS can be thought of as facts and their arguments in Prolog, respectively. Although ECS and Prolog may not necessarily be fully analogous to each other from a technical standpoint, they do share pretty much the same motivation in the sense that they both make the gameplay logic highly parallelizable and data-driven.

Here is an example of what a purely ECS-based game engine would look like. It is a custom HTML5 game engine I wrote using Typescript and WebGL, and it supports both rudimentary 3D graphics and real-time physics. It does not fully leverage the multithreading capability of ECS, yet it does manage to render its structural elegance. In this repository, you will see many similarities between the engine's data-driven systems and the rules I have been writing in Prolog.

Of course, the gameplay system will just be a silent blackbox unless it displays things on the screen, emits sound, and takes input from the user (via mouse, keyboard, etc).

You know that Prolog, by default, is not a fitting language for general-purpose software development. And because of that, there has not been many popular input/output frameworks (e.g. GUI) designed to work nicely in a Prolog-based programming context.

Since what I am proposing in this article is a kind of "virtual Prolog machine" which is different from the standard Prolog environment, however, nothing really prevents us from attaching external I/O endpoints to it, thereby letting this quasi-Prolog system freely interact with the rest of the game engine.

Let me start with user inputs. In Part 4, I supposed that there will eventually be some sort of "I/O utility" for the Prolog script to use, such as ones which let the system tell whether the user is currently pressing the given key on the keyboard, and so forth. With the aforementioned transcompilation approach (i.e. translation of the Prolog code into its C# equivalent), this kind of design won't be hard to implement at all. For example, if we decide to write the following code (shown below) to let the player character move to the left whenever the left arrow key is pressed,

moveLeft[n](X) :- player[n](X), IO::keyPressed(IO::leftKey).The only thing we will need to do is let the transcompiler recognize the prepended keyword "IO" and look up all of its referenced methods/constants in the separately implemented static class called "IO". Such a class will be the place where the game's IO-related functions will be located (See the code below).

public static class IO

{

public static leftKey = KeyCode.LeftArrow;

public static bool keyPressed(KeyCode keyCode)

{

return Input.GetKey(keyCode);

}

...

}And, just like in the "MATH" utility example which I introduced before, the "IO" utility will be directly accessed by the Prolog rules whenever they encounter the prefix "IO". The code below, for instance, is the C# equivalent of the "moveLeft" rule shown above. You can see here that the second relation of the rule (i.e. "keyPressed") gets evaluated not by looking up a dictionary of available facts, but by directly calling the appropriate function in the IO class.

public class Rule_moveLeft : Rule

{

public override int Evaluate(int n, State[] states)

{

int numNewFactsDerived = 0;

State currState = states[n % states.Length];

foreach (var X in currState.player)

{

if (IO.keyPressed(IO.leftKey))

{

if (!currState.moveLeft.Contains(X))

{

currState.moveLeft.Add(X);

numNewFactsDerived++;

}

}

}

return numNewFactsDerived;

}

}What about the output part of the game? As you may have already realized, outputs are not so fundamentally distinct from inputs when it comes to transcompilation. The "IO" utility class I have illustrated above can be used for output-related Prolog relations as well; they just happen to be serving slightly different purposes.

There indeed are many aspects of a computer program which could be referred to as "output", including graphics, sound, outgoing file streams, outgoing packets in a network, and so on. The most important of them, though, is probably graphics. A video game can be played without sound or networking, but it cannot be played without displaying anything on the screen. Thus, let me start with a graphics-related example.

In a typical 3D game, we render an actor by identifying its position and rendering a mesh of its type there. In Prolog, such a line of logic should be realizable by means of direct access to external utility functions. A brief demonstration of this idea is shown below.

mesh[n](X, "bread.fbx") :- bread[n](X).

IO::renderMesh(M, P) :- mesh[n](X, M), position[n](X, [single]P).Here, a fact of type "mesh" lets the system identify the mesh of any "bread" actor as the 3D asset whose file path is "bread.fbx". As long as an actor is a piece of bread, its mesh is supposed to be "bread.fbx".

The second horn clause is the the rule which is responsible for displaying the "bread.fbx" mesh on the screen by calling the IO class's "renderMesh" function whenever a bread happens to exist at a specific location. Such a function will then request the game's graphics engine to render an instance of "bread.fbx" at the designated spot.

public static class IO

{

...

public static void renderMesh(Mesh M, (int, int) P)

{

RenderParams rp = new RenderParams(getMaterialForMesh(M));

Graphics.RenderMesh(rp, M, 0,

Matrix4x4.Translate(new Vector3((float)P.Item1, (float)P.Item2, 0f)));

}

...

}More advanced output functionalities, too, can be constructed via IO functions and a handful of information-relaying facts. A "cat prefab" which plays its own animation and sound whenever it eats something, for instance, will be able to be instantiated via the game engine's dynamic allocator (which is separate from Prolog's fact-tracking logic). The code below is a demonstration of this.

IO::createGameObject(X, "cat.prefab") :- spawned[n-1](X, Src, Cause, Pos), cat[n](X).

IO::destroyGameObject(X) :- despawn[n](X).

eatingPosition[n](X, P) :- eat[n](X, Food), position[n](X, [single]P).

IO::playAnim(GO, "eat") :- eatingPosition[n](X, [single]P), IO::getGameObject(X, GO).

IO::playSound(GO, "eat") :- eatingPosition[n](X, [single]P), IO::getGameObject(X, GO).Last but not least, we also ought not to neglect the importance of logging (i.e. debugging) in a gameplay system. It will help us troubleshoot errors by providing us with detailed clues in regard to what was going on while the game was running.

Logging, too, should be able to be carried out via externally implemented utility functions. The Prolog rule displayed below is an example of how we can order the system to print out a log message whenever an actor spawns.

LOG::write("Spawned new actor ({Id}) at time {n}") :-

spawned[n](Id, Src, Cause, Pos).When pattern-matched, such a rule will simply invoke the LOG class's "write" function with the given string parameter instead of trying to register a new fact of type "write".

public static class LOG

{

public static void write(string message)

{

Debug.Log(message);

}

}Labelling debug-related method calls with the word "LOG" comes with its own additional advantage, which is the ability for the transcompiler to exclude them when asked to produce the final production build. The process of logging itself incurs its own computational cost, which means that, once the development process is over, rules which are dedicated to logging should no longer be included for the sake of optimization.

At this point, you might have noticed that some of the rules introduced so far (especially the ones which simply invoke external methods) are not supposed to be evaluated multiple times during the same exact time frame. Unfortunately, the possibility of mutual dependencies amongst the Prolog rules obliges us to keep evaluating them over and over until no more new facts can be drawn out of them.

There is a simple fix for this, though. First of all, let us go back to the initial implementation of the virtual Prolog machine's "Update()" method (I will reproduce it below).

public class VirtualPrologMachine

{

...

public void Update()

{

int currStateIndex = n % states.Length;

// Delete facts that are too old.

states[currStateIndex].Clear();

// Evaluate the rules until no more new facts can be derived.

int numNewFactsDerived = 0;

int trial = 0;

do

{

foreach (var rule in rules)

{

numNewFactsDerived += rule.Evaluate(n, states);

}

} while (++trial > 3 || numNewFactsDerived == 0);

n++;

}

}As you can see, the current C# code repeatedly evaluates ALL of the given rules while it manages to infer at least one new fact out of them. This, of course, will be inappropriate for rules which should never be evaluated multiple times within the same update frame, such as: "IO::renderMesh(M, P) :- mesh[n](X, M), position[n](X, [single]P)" (because drawing the same mesh over and over is wasteful).

Thus, we will need to add some additional properties to each Rule class to be able to control its nature of repetitive evaluation. For example, we may consider adding two new fields which are respectively called "EvalCount" and "MaxEvalCountPerTimeStep", where "EvalCount" indicates the number of times the rule has been evaluated during the current frame and "MaxEvalCountPerTimeStep" indicates the maximum number of times the rule should ever be allowed to be evaluated during the current frame.

public abstract class Rule

{

public int EvalCount = 0;

public abstract int MaxEvalCountPerTimeStep { get; }

public abstract int Evaluate(int n, State[] states);

}Then, the virtual Prolog machine's "Update()" procedure will be able to selectively re-evaluate the rules based upon their current EvalCount values. A rule whose MaxEvalCountPerTimeStep is set to 1, for instance, will be evaluated only once even if it gets visited multiple times during multiple iterations of the do-while loop.

public class VirtualPrologMachine

{

...

public void Update()

{

int currStateIndex = n % states.Length;

// Delete facts that are too old.

states[currStateIndex].Clear();

// Reset the evaluation counts.

foreach (var rule in rules)

rule.EvalCount = 0;

// Evaluate the rules until no more new facts can be derived.

int numNewFactsDerived = 0;

do

{

foreach (var rule in rules)

{

if (++rule.EvalCount <= rule.MaxEvalCountPerTimeStep)

numNewFactsDerived += rule.Evaluate(n, states);

}

} while (numNewFactsDerived == 0);

n++;

}

}Let me show you a specific example of this. First, take a look at the following line of Prolog code; it is the "renderMesh" rule I have introduced before. Since its sole responsibility is to render each actor's mesh onto the screen, we do not want this rule to be evaluated more than once during each frame.

IO::renderMesh(M, P) :- mesh[n](X, M), position[n](X, [single]P).Therefore, the Prolog transcompiler will need to be programmed to recognize such a special rule (by noticing that the result of the rule is an external IO method call instead of the derivation of a new fact) and set its "MaxEvalCountPerTimeStep" to 1 accordingly. The following C# class is the implementation of it.

public class Rule_IO_renderMesh : Rule

{

public override int MaxEvalCountPerTimeStep => 1;

public override int Evaluate(int n, State[] states)

{

State currState = states[n % states.Length];

foreach (var kvp1 in currState.mesh)

{

var X = kvp1.Key;

var M = kvp1.Value;

if (currState.position.ContainsKey(X))

{

var P = currState.position[X];

IO.renderMesh(M, P);

}

}

return 0;

}

}(Side Note: Another way to solve the problem of repetitive evaluation is to simply force the game loop to evaluate its rules only once during each frame, after making sure that each rule only contains references to the past (n-1, n-2, etc) on its right-hand side relations. This will inevitably produce quite a bit of delay when generating a chain of facts (e.g. spawning a bread causes it to be labelled as "bread" after a delay of 1 time step, which in turn will subsequently cause it to be labelled as "edible" after yet another delay of 1 time step, and so on), but doing this will render repeated rule-evaluation totally unnecessary.)

Besides those related to I/O, there are other gameplay subsystems such as physics, AI, etc. While it is not entirely impossible to implement such features in Prolog, the efficiency of the end result is more or less doubtful.

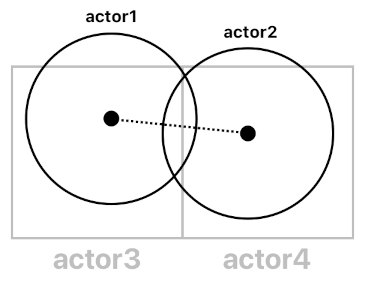

The code shown above is an example of how you could simulate real-time collision between two circles in Prolog. Notice that there are so many things going on here, yet the overall idea is that the following set of rules will detect collision on a uniform voxel grid (where each voxel is treated as an actor) by checking a series of conditions.

circleCollider(actor1, 0.5).

circleCollider(actor2, 0.5).

voxel(actor3, <0, 0>).

voxel(actor4, <1, 0>).

voxelsIntersect(actor3, actor3).

voxelsIntersect(actor4, actor4).

voxelsIntersect(actor3, actor4).

voxelsIntersect(actor4, actor3).

getVoxelAt(Pos, Voxel) :-

voxel(Voxel, [single]P), x(P, X), y(P, Y),

MATH::absDiff(P, Pos, DiffX), MATH::absDiff(P, Pos, DiffY),

MATH::lessThanOrEqualTo(DiffX, 0.5), MATH::lessThanOrEqualTo(DiffY, 0.5).

actorIsInVoxel[n](X, Voxel) :- position[n](X, [single]Pos), getVoxelAt(Pos, Voxel).

actorsMayCollide[n](X, Y) :-

circleCollider[n](X, _), circleCollider[n](Y, _),

actorIsInVoxel[n](X, Voxel1), actorIsInVoxel[n](Y, Voxel2),

voxelsIntersect([key]Voxel1, [key]Voxel2).

collide[n](X, Y) :-

actorsMayCollide[n]([key]X, [key]Y),

circleCollider[n](X, [single]Rx), circleCollider[n](Y, [single]Ry),

position[n](X, [single]Px), position[n](Y, [single]Py),

MATH::add(Rx, Ry, DistThres), MATH::absDiff(Px, Py, Dist),

MATH::lessThanOrEqualTo(Dist, DistThres).

The problem with this kind of approach is that there are just too many things to compute here. It forces the gameplay system to evaluate a bunch of rules, each of which only contributes to a fraction of the full collision detection process (i.e. one for identifying actors in each voxel, another one for voxel adjacency check, plus another one for distance comparsion, etc).

This might not be too bad, as long as we manage to parallelize and/or pipeline these rules in an elegant manner. Will this strategy outperform a dedicated physics engine, though?

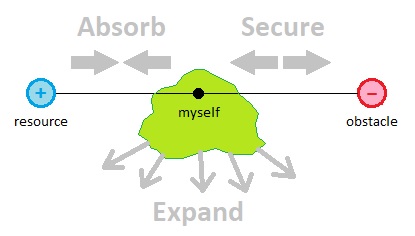

As I had mentioned in the first section of Part 1, the aim of Prolog-based game programming in this series of articles is to figure out how to construct the core gameplay logic based upon the language of Prolog. The reason behind the presumption of such specialization is that a declarative language is not necessarily optimized for aspects of the game which are not so easy to model in terms of logical relations, such as physics, graphics, etc.

Besides, it is a bit of a wasted effort to try to reinvent the wheel which already works nicely. And we should also remind ourselves that such a wheel is highly modular in nature, that it is quite trivial to just grab and use it as a blackbox.

The code below shows how an external "physics library" could be used within the context of Prolog rules. The idea is that you simply access/modify each actor's collision status via external utility functions, and make gameplay-related decisions off of it.

mechanicalForce[n](X, [acc]F) :-

PHYS::getCollidingPairs(X, Y),

PHYS::getOverlappingVolume(X, Y, V), stiffness[n](X, [single]St),

MATH::multiply(V, St, F).

say[n](X, "Ouch! Don't hit me hard.") :-

mechanicalForce[n-1](X, F), MATH::length(F, L), MATH::greaterThan(L, 10).Advanced gameplay AI features, too, should probably follow the same design philosophy. Complex decision-making algorithms, such as that of A* pathfinding, have their own procedures nicely encapsulated as external libraries. Thus, it is probably wise to separate such pieces of behavioral logic from the core set of Prolog-based gameplay rules.

The code shown below is a demonstration of how the game's pathfinder can easily be separated into its own external module. The logic which drives an actor to follow a path will have to be part of the Prolog script, but the job of pathfinding itself can simply be undertaken by external utility functions.

AI::calculateNewPath(X, TargetPos) :-

chasing[n](X, Target),

AI::getCurrentPath(X, Path), !AI::isPathValid(Path),

position[n](Target, TargetPos).

move[n](X, NextPos) :-

AI::getCurrentPath(X, Path), AI::isPathValid(Path),

position[n](X, [single]P), speed[n](X, [single]S),

AI::getNextPosInPath(X, P, S, Path, NextPos).I believe that, at this point, I have gone over pretty much all major aspects of Prolog-based game development.

First of all, I explained how some of the core game mechanics (e.g. births, deaths, interactions, semantic relations, hierarchies, etc) could be devised in the language of Prolog without too much difficulty.

And then, I spent quite a bit of time explicating the details of how a Prolog script is able to be transcompiled into its imperative (e.g. C#) analogue, thus allowing the computer to run it with utmost efficiency.

I also mentioned ways in which external libraries could be utilized by letting them communicate with our "virtual Prolog machine" through special endpoints, thereby supplementing some of the functional deficiencies of the Prolog-based logic system.

There is one missing piece of puzzle which I have not gone over yet, though. It is the problem of integrating the aforementioned techniques into the very design of the game itself.

The concepts I have illustrated so far only covered the implementation side of the game. The problem is that, if we want to implement something, we must at least partially contribute to the design of it in the first place.

One might reject this notion by saying, "Oh, it's the designer's job. Engineers have nothing to do with how the game shall be designed". However, I would insist that design and engineering are inseparable aspects of the same coin, and thus must be able to collaborate under the same underlying system.

A great furniture designer is one who understands the basics of human-centered engineering as well as the economics of manufacturing, and a great airplane designer is one who understands the basics of aerodynamics as well as control theory. One does not simply "design an airplane", give its concept art to a nerd who does all the math and stuff, and say, "Now, make it fly!"

A similar line of reasoning should apply to the subject of game design as well.

When developing something, one does not simply contrive its individual parts (which do not necessarily fit each other well), duct-tape them together, and call it a well-functioning product; that's what amateurs do, despite the fact that many of them constantly manage to save their ass due to the low visibility of tech debt accruing on the backs of their hard-working yet unsung fellows.

Both design and implementation are parts of the same underlying process. Therefore, it is not absurd to claim that the success in the establishment of these individual parts depends on the understanding of both.

Knowing how to program a game using Prolog is indeed a valuable asset to have in one's skillset. Yet, this alone does not quite complete the full picture of what endows a video game with its own long-lasting spirit. Besides mastering the hidden intricacies of programming, one must also learn how to incorporate them in the grand scheme of game design, which includes mechanics, narratives, and the philosophy of its inner worldview.

There is another series of articles I wrote back in 2023, Universal Laws of Game Design, which expounds this interdisciplinary topic in detail. If you are interested in expanding the scope of your reading material beyond that of mere technical elaboration, please check this out.

(End of "Game Programming in Prolog")

Previous Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service