Author: Youngjin Kang Date: September 4, 2024

This is Part 4 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

A playable game must have its own space and time. It is because space without time is a mere snapshot, and time without space is a mere point.

In the last article, I explained the nature of time and how its progression could be conceptualized in the language of Prolog. However, I have not explained yet how to express the concept of space in Prolog. Since spatial reasoning is an indispensable part of almost all video games (except ones that are entirely text-based), being able to construct spatial elements and let them spatially interact with one another is crucial for the design of game mechanics.

So, how to express the idea of space in Prolog? In order to achieve this goal, we must first unlearn the traditional methods in computational geometry which are only appropriate for the imperative paradigm. Then, we ought to figure out how to model space as a collection of relations such as position, proximity, distance, direction, etc.

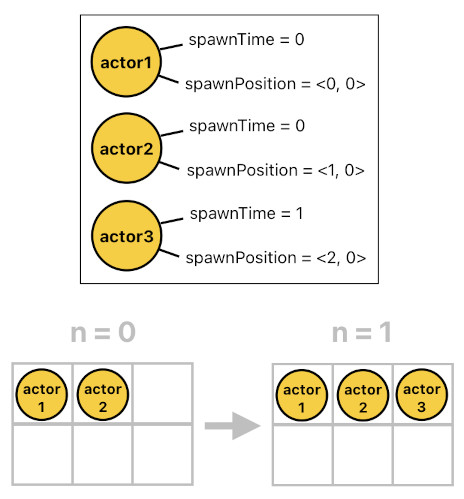

Let us first start with a few actors, assuming that we are able to specify each actor's spawn time as well as spawn position (The notation "<x, y>" refers to a vector quantity). Suppose that there are three of them, named "actor1", "actor2", and "actor3", respectively. Their declarations are displayed in the following code.

spawnTime(actor1, 0).

spawnPosition(actor1, <0, 0>).

spawnTime(actor2, 0).

spawnPosition(actor2, <1, 0>).

spawnTime(actor3, 1).

spawnPosition(actor3, <2, 0>).

In this scenario, actor1 was born at time 0 and position <0, 0>, actor2 was born at time 0 and position <1, 0>, and actor3 was born at time 1 and position <2, 0>. This allows us to locate these three actors not just in time but also in space.

Of course, the statements above only show us where they were located when they were born. If there is no additional rule, we will be forced to assume that the positions of these three actors will simply be "undefined" shortly after they were born (because there won't be any "position(...)" predicate which will correspond to future time steps).

Thus, further elaboration is needed in order to ensure their spatial persistence. The following code illustrates how it can be achieved.

position(X[n], P) :- spawnTime(X, n), spawnPosition(X, P).

position(X[n], P) :- move(X[n-1], P).

position(X[n], P) :- !move(X[n-1], _), position(X[n-1], P).

The first horn clause defines the base case, which says, "If actor X is created right now at position P, its current position must be P". This makes sense, doesn't it? If something is initially placed somewhere and absolutely no time has passed since then, we must be able to assert that its current position is identical to its initial position.

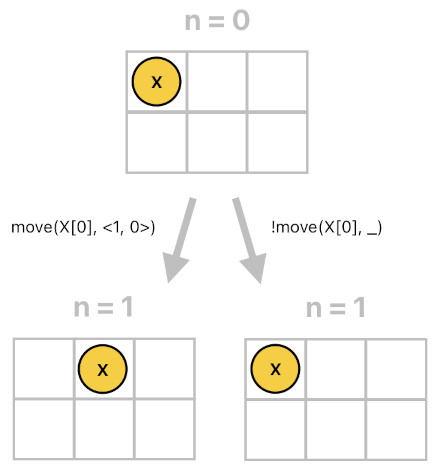

The second and third horn clauses specify the two alternative cases of recursion (This is an example of the so-called "decision tree").

The second horn clause tells us that if X moved to P during the previous time step, its current position must be P. Here, the "move" relation is plays the role of a differential which gets accumulated (integrated) into X's position as time elapses. This horn clause, thus, can be thought of as an accumulator (integrator) which produces the cumulative sum of the input stream of moves.

The third horn clause defines the "fallback" condition, which tells us that X's position should stay as it was before if X did not move at all. This, together with the second clause, ensures that X's position is always defined regardless of whether X has moved during the preceding time step or not. If X moved, the second clause would be activated. If X did NOT move, the third clause would be activated instead. This is Prolog's way of implementing the IF-ELSE logic.

This sounds reasonable so far. However, the rules above only tell us how to update an object's position based on its momentum. They do not tell us how the momentum itself shall be generated in the first place.

What makes an object move? There really are innumerable forces which may contribute to its motion, so it is probably a bit too cumbersome to list them all here. Thus, I will first begin with one of the most common means of triggering a movement in a video game - a keyboard-based character control.

The logic I am going to expound here is pretty simple. Suppose that there is a main character I want to control in a top-down 2D game. If I were to play it on a PC, I would expect myself to be able to control the character's left, right, up, and down movements by pressing the four arrow keys on the keyboard (i.e. "left arrow", "right arrow", "up arrow", and "down arrow").

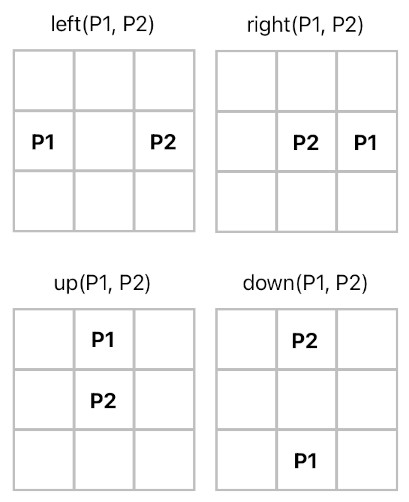

In order to implement this mechanic, we ought to first let Prolog know what we mean by "left", "right", "up", and "down". The semantics of these four words are specified below.

left(P1, P2) :- x(P1, X1), x(P2, X2), y(P1, Y1), y(P2, Y2), equal(Y1, Y2), add(X1, C, X2), greaterThan(C, 0).

right(P1, P2) :- x(P1, X1), x(P2, X2), y(P1, Y1), y(P2, Y2), equal(Y1, Y2), add(X2, C, X1), greaterThan(C, 0).

up(P1, P2) :- x(P1, X1), x(P2, X2), y(P1, Y1), y(P2, Y2), equal(X1, X2), add(Y1, C, Y2), greaterThan(C, 0).

down(P1, P2) :- x(P1, X1), x(P2, X2), y(P1, Y1), y(P2, Y2), equal(X1, X2), add(Y2, C, Y1), greaterThan(C, 0).

The "x(P, Xc)" relation asserts that the x-component of position P is Xc, and the "y(P, Yc)" relation asserts that the y-component of position P is Yc. This means that, in all of the four horn clauses listed above, the following definitions hold:

P1 = <X1, Y1>

P2 = <X2, Y2>The idea here is to identify the type of direction which can be implied by a pair of positions: P1 and P2. For example, if it is possible to make P1 identical to P2 by adding a positive number to P1's x-component, we can say that P1 is to the left of P2. Or, if it is possible to make P2 identical to P1 by adding a positive number to P2's x-component, we can say that P1 is to the right of P2.

These four directional relations, however, are not descriptive enough to define all the spatial properties we need. For instance, they only tell us about directions; they do not involve the concept of distance whatsoever (which means that they cannot answer questions such as, "How much do I have to travel from P2 to the left to reach P1?", etc).

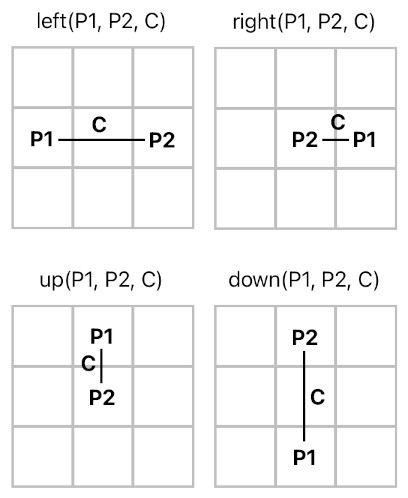

A slight revision ought to be made to fill out the missing information. The following code shows the same set of horn clauses demonstrated above, except that they are now equipped with the third parameter ("C") which tells us how far apart P1 is from P2.

So, for example, if you write the predicate "left(P1, pos2, c)", with the value of "pos2" and "c" specified and the value of "P1" being left as unknown, it will compute the value of P1 which is to the left of "pos2" by the distance of "c".

left(P1, P2, C) :- x(P1, X1), x(P2, X2), y(P1, Y1), y(P2, Y2), equal(Y1, Y2), add(X1, C, X2), greaterThan(C, 0).

right(P1, P2, C) :- x(P1, X1), x(P2, X2), y(P1, Y1), y(P2, Y2), equal(Y1, Y2), add(X2, C, X1), greaterThan(C, 0).

up(P1, P2, C) :- x(P1, X1), x(P2, X2), y(P1, Y1), y(P2, Y2), equal(X1, X2), add(Y1, C, Y2), greaterThan(C, 0).

down(P1, P2, C) :- x(P1, X1), x(P2, X2), y(P1, Y1), y(P2, Y2), equal(X1, X2), add(Y2, C, Y1), greaterThan(C, 0).

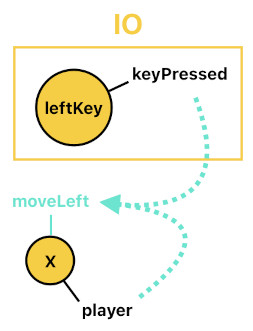

Now that we've got all the necessary ingredients, let us devise the keyboard-based control logic. Suppose that Prolog is equipped with a special library called "IO", which provides built-in predicates for the computer's input/output signals such as "key pressed", "mouse button pressed", "mouse position", "speaker volume", and so on. "IO::keyPressed(X)", for instance, will be interpreted as TRUE whenever key X is being pressed.

With this hypothetical library in mind, we can devise motion-related control flags as predicates, like the ones written below.

moveLeft(X[n]) :- player(X[n]), IO::keyPressed(IO::leftKey).

moveRight(X[n]) :- player(X[n]), IO::keyPressed(IO::rightKey).

moveUp(X[n]) :- player(X[n]), IO::keyPressed(IO::upKey).

moveDown(X[n]) :- player(X[n]), IO::keyPressed(IO::downKey).

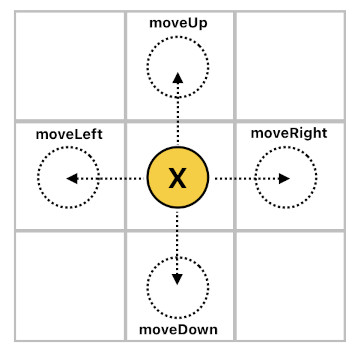

The basic idea is that there are four different commands for the player's movement - "moveLeft", "moveRight", "moveUp", and "moveDown". Whenever "moveLeft" gets triggered, the player character (i.e. any actor which is labeled as "player") should move to the left, and whenever "moveRight" gets triggered, the player character should move to the right, and... you get the idea.

And as you can see from the above horn clauses, the keyboard's left, right, up, and down arrow keys will respectively trigger these four commands, thereby letting the player move in four different directions.

But of course, these commands are not going to do anything unless we give them specific instructions as to the actual movement of the character.

You may recall that I have previously introduced the "move(...)" predicate as means of changing the actor's current position. "move(X[n], NewPos)", for example, will generate a force which will set the position of actor "X" to the value of "NewPos" by the moment at which the time step shifts from "n" to "n+1" (i.e. when the clock ticks).

So in order to construct the movement logic, all we need to do is come up with rules which will set the value of the "move(...)" predicate to TRUE whenever the right set of conditions are satisfied. In our case, such rules can be specified as the ones listed below.

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveLeft(X[n]), position(X[n], P), left(NewPos, P, 1).

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveRight(X[n]), position(X[n], P), right(NewPos, P, 1).

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveUp(X[n]), position(X[n], P), up(NewPos, P, 1).

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveDown(X[n]), position(X[n], P), down(NewPos, P, 1).

The four horn clauses above are responsible for handling the four movement commands (i.e. "moveLeft", "moveRight", "moveUp", and "moveDown").

Let us take a look at the first one. If the "moveLeft" command is raised and actor X is currently located at P, "left(NewPos, P, 1)" will find the position "NewPos" which is located to left of P by the distance of 1 (because that's the only value of "NewPos" which makes "left(...)" true). This position, then, will be the destination of actor X in its subsequent motion. The other 3 horn clauses work the same way, just in different directions.

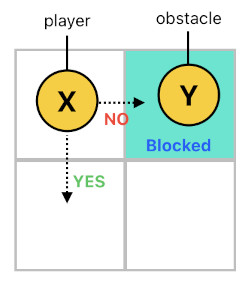

There is something missing here, though. The rules stated so far do let us control our player using the arrow keys, yet there is no limit when it comes to locomotive freedom. We can move the character in any way we want, which is not the kind of mechanic we would like to have in a game where the presence of movement constraint is crucial (e.g. maze escape game).

A simple way to fix this flaw is to add an extra predicate to each horn clause to check whether the destination (i.e. NewPos) is blocked by an obstacle. This check can be done by trying to find an actor which is labeled as an "obstacle" and is located at the given position. If such an actor is found, the position must be considered "blocked". The "positionBlocked(...)" predicate in the following code carries out this task, which will be used for the purpose of allowing the player's move only if the destination is NOT being blocked (i.e. "!positionBlocked(NewPos)").

positionBlocked(P) :- obstacle(X[n]), position(X[n], P).

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveLeft(X[n]), position(X[n], P), left(NewPos, P, 1), !positionBlocked(NewPos).

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveRight(X[n]), position(X[n], P), right(NewPos, P, 1), !positionBlocked(NewPos).

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveUp(X[n]), position(X[n], P), up(NewPos, P, 1), !positionBlocked(NewPos).

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveDown(X[n]), position(X[n], P), down(NewPos, P, 1), !positionBlocked(NewPos).

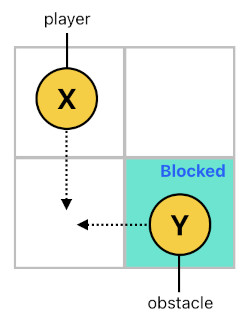

There is something fishy in the solution I just illustrated, however. As you may have already noticed, a problem arises when the player and an obstacle happen to be moving to the same exact location at the same exact time, in which case they will overlap. This is clearly undesirable because the player is not supposed to be able to penetrate through an obstacle.

This bug, of course, is caused by the fact that the rules are only checking the obstacle's current location. In order to prevent the player and the obstacle from colliding due to simultaneous movement, we must make sure that no obstacle is going to be present at the player's destination not only during the current time step, but also during the next time step. The following code amends the rules to meet this requirement.

currOrNextPositionBlocked(P) :- obstacle(X[n]), position(X[n], P).

currOrNextPositionBlocked(P) :- obstacle(X[n]), move(X[n], P).

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveLeft(X[n]), position(X[n], P), left(NewPos, P, 1), !currOrNextPositionBlocked(NewPos).

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveRight(X[n]), position(X[n], P), right(NewPos, P, 1), !currOrNextPositionBlocked(NewPos).

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveUp(X[n]), position(X[n], P), up(NewPos, P, 1), !currOrNextPositionBlocked(NewPos).

move(X[n], NewPos) :- moveDown(X[n]), position(X[n], P), down(NewPos, P, 1), !currOrNextPositionBlocked(NewPos).Still, however, we cannot fully guarantee that nothing buggy is going to occur. What if the obstacle's intention to move to the player's destination (i.e. "move(...)") gets activated AFTER the "currOrNextPositionBlocked(...)" check has already been done? In such a case, collision may ensue.

Of course, just as I have mentioned in the last article, this kind of subtlety (which is due to the order of operation) may be circumvented by letting the Prolog interpreter scan the rules twice instead of just once, etc. But again, it is computationally expensive.

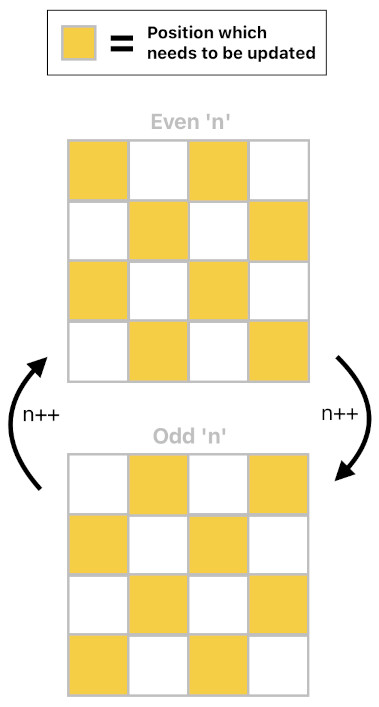

A more elegant solution is to introduce an interleaving mechanism to the game loop, forcing it to update only half of the world's 2D array of positions at every even-numbered time step, and the other half at every odd-numbered time step. Each half consists of positions which are guaranteed not to immediately influence each other during the current time step. A graphical depiction of this technique is shown below.

(Side Note: I have previously suggested a similar idea in: Parallel Adjacent-Cell Modification Support for General-Purpose Cellular Automata)

And the following lines are the corresponding code implementation. Note that "mod(A, B, C)" computes C based upon the rule "A % B = C", and "xor(A, B, C)" computes C based upon the rule "A ^ B = C".

inEvenTimeSlot(P) :- x(P, Px), y(P, Py), mod(Px, 2, Mx), mod(Py, 2, My), xor(Mx, My, 0).

inOddTimeSlot(P) :- x(P, Px), y(P, Py), mod(Px, 2, Mx), mod(Py, 2, My), xor(Mx, My, 1).

shouldUpdatePosition(P) :- mod(n, 2, 0), inEvenTimeSlot(P).

shouldUpdatePosition(P) :- mod(n, 2, 1), inOddTimeSlot(P).

...

position(X[n], P) :- move(X[n-1], P), position(X[n-1], PrevPos), shouldUpdatePosition(PrevPos).(Will be continued in Part 5)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service