Author: Youngjin Kang Date: 2022

The Cellular Automata (CA) model is useful for many applications, such as grid-based videogames, integrated circuit simulations, ecological simulations, particle simulations, and so on. One major limitation of a typical CA system, however, is that each cell is only allowed to modify its own state. This is not a problem when we are dealing with a simple mathematical thought experiment such as Conway's Game of Life, but can really turn out to be a serious bottleneck when we try to establish some form of "Conservation of Matter" in CA, in which an object simply transfers from one location to another instead of allowing itself to be created/destroyed.

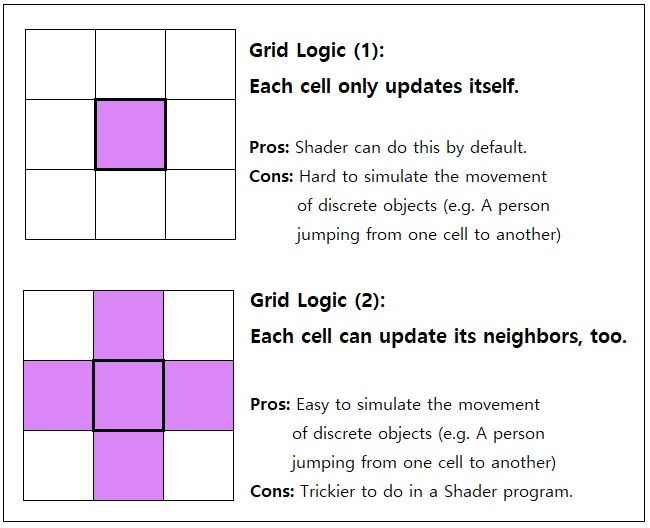

There are two possible methods of logic for a CA system, which are shown above. The first one is the standard CA logic that can easily be implemented as a shader (or any other equivalent parallel-processing) program, and the other one is a modified CA logic which allows each cell to modify the state of its neighbors, not just its own. This lets us simulate the movement of discrete objects, since a "movement" is nothing more than a simple data-swap between two adjacent cells.

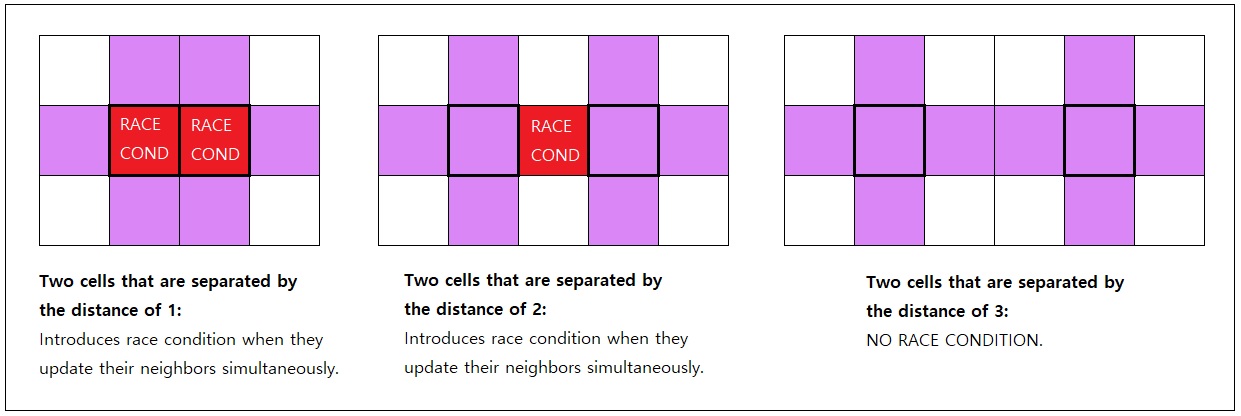

Allowing each cell to simultaneously modify its neighbors, of course, has its own drawbacks. If we allow two adjacent cells to concurrently update their own neighbors, we will be facing race conditions within these two cells. If we allow two cells that are separated by only one other cell to concurrently update their own neighbors, we will still be facing race conditions within this in-between cell.

If we allow two cells that are separated by TWO other cells instead of just one, however, we won't experience any race conditions between them because there will be no way for them to modify the same cell at once.

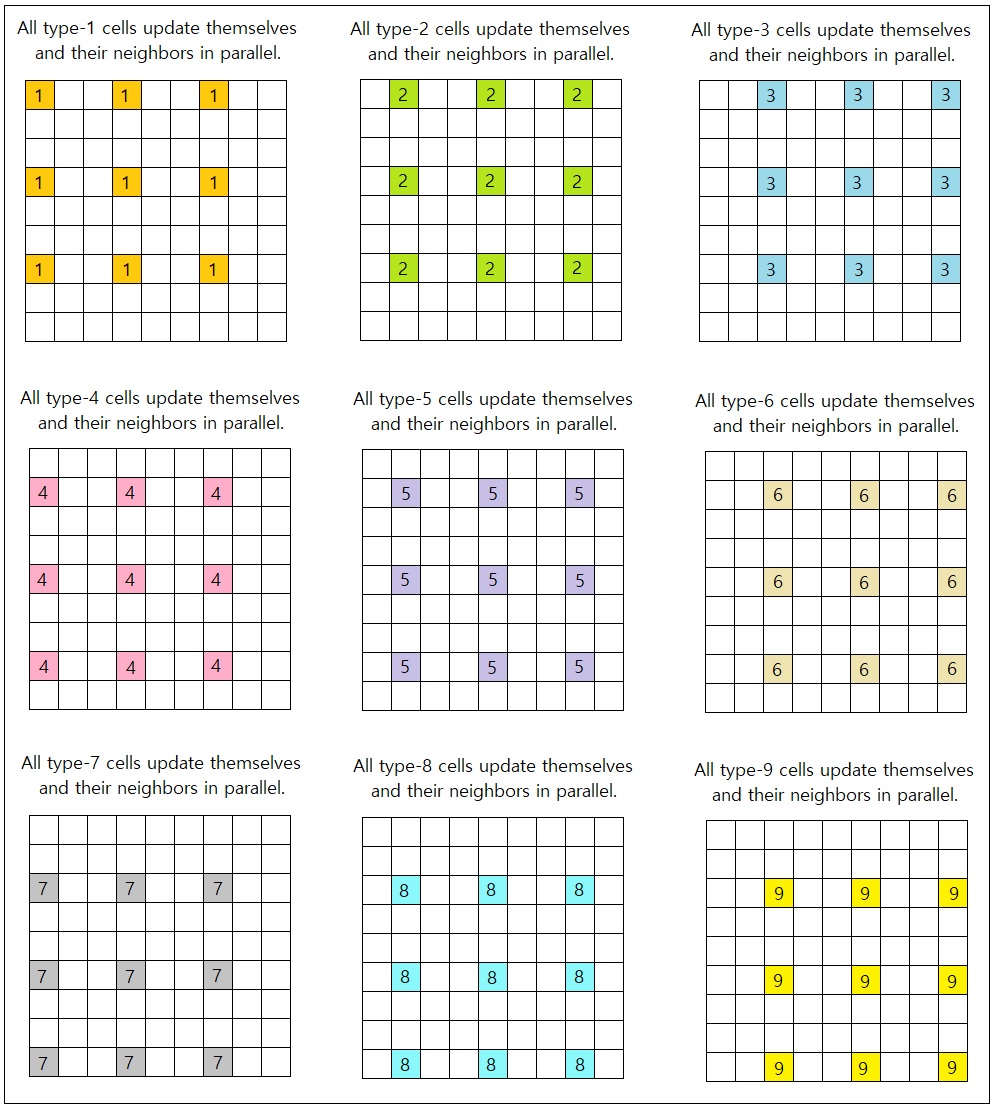

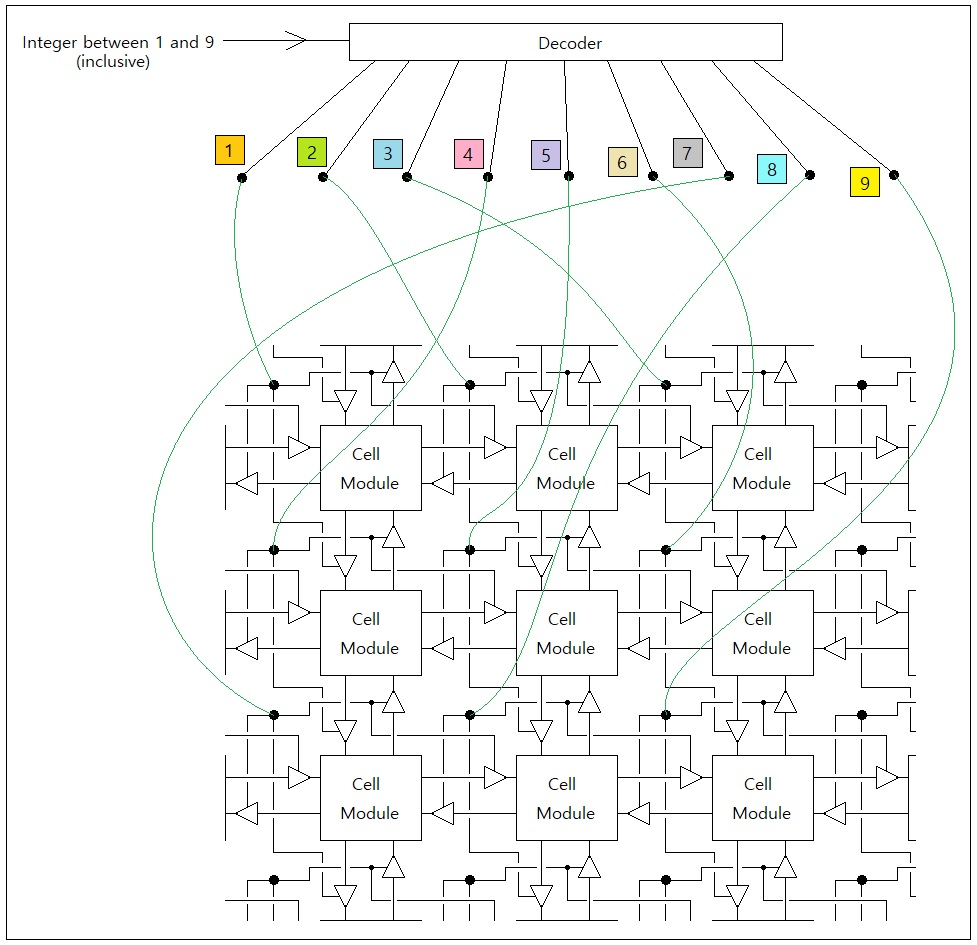

This means that, in order to let every cell modify its neighbors in a concurrent manner, we must slice the parallel update routine of the CA into 9 different modes, each of which contains one of 9 unique sets of cells that are separated by at least 2 other cells between them. This ensures that absolutely no race condition can happen during any of these 9 modes, since no pair of cells will have a chance to touch the same exact neighboring cell.

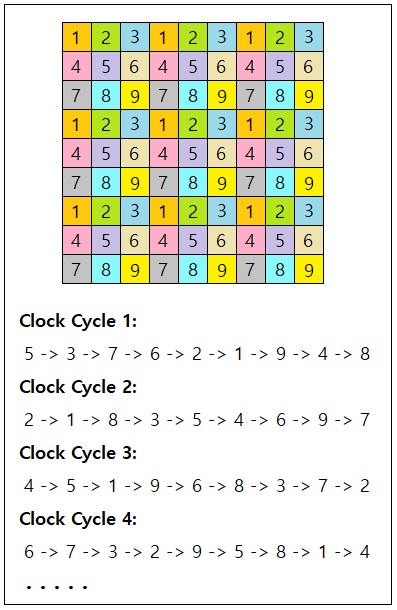

Updating the entire CA grid, then, will require the program to execute all of these 9 modes in a sequential manner during each full update cycle. A simple design is to run these modes in a numerically ascending order, such as: [1 -> 2 -> 3 -> 4 -> 5 -> 6 -> 7 -> 8 -> 9]. However, such a fixed order may introduce "biases" to the system, causing side effects such as object movements always tending towards certain directions, etc. Therefore, it is much more desirable to shuffle the order of these 9 execution modes after each full update cycle of the CA, so as to "average out" such potential biases.

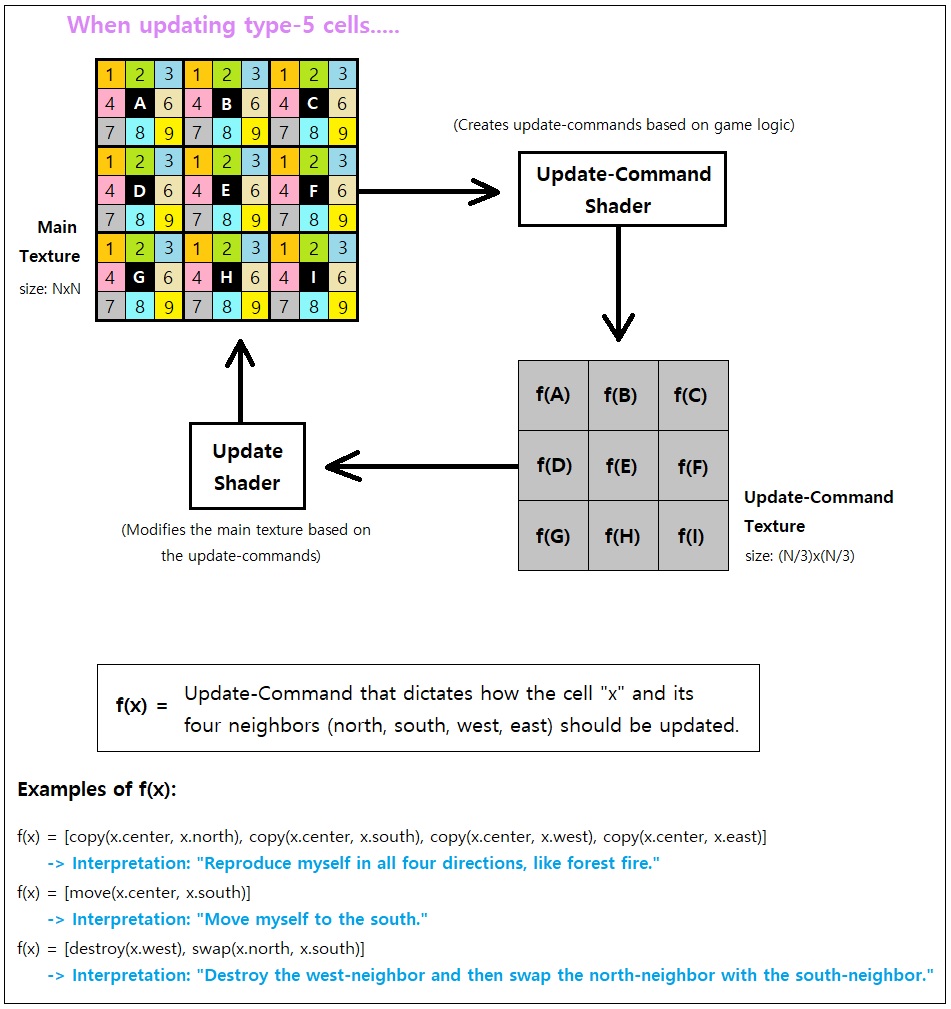

The aforementioned method can be implemented as a shader program pretty easily. All we need is a pair of shaders, one for issuing "update-commands" based on the current state of the cell and its neighbors, and the other for interpreting these update-commands and applying the appropriate state changes to the cell as well as its neighbors. The CA cell's state can be encoded as a pixel value (32 bits for a standard RGBA texture), and each update-command's content (i.e. opcodes and their parameters), too, can be encoded as a pixel value (32 bits for a standard RGBA texture).

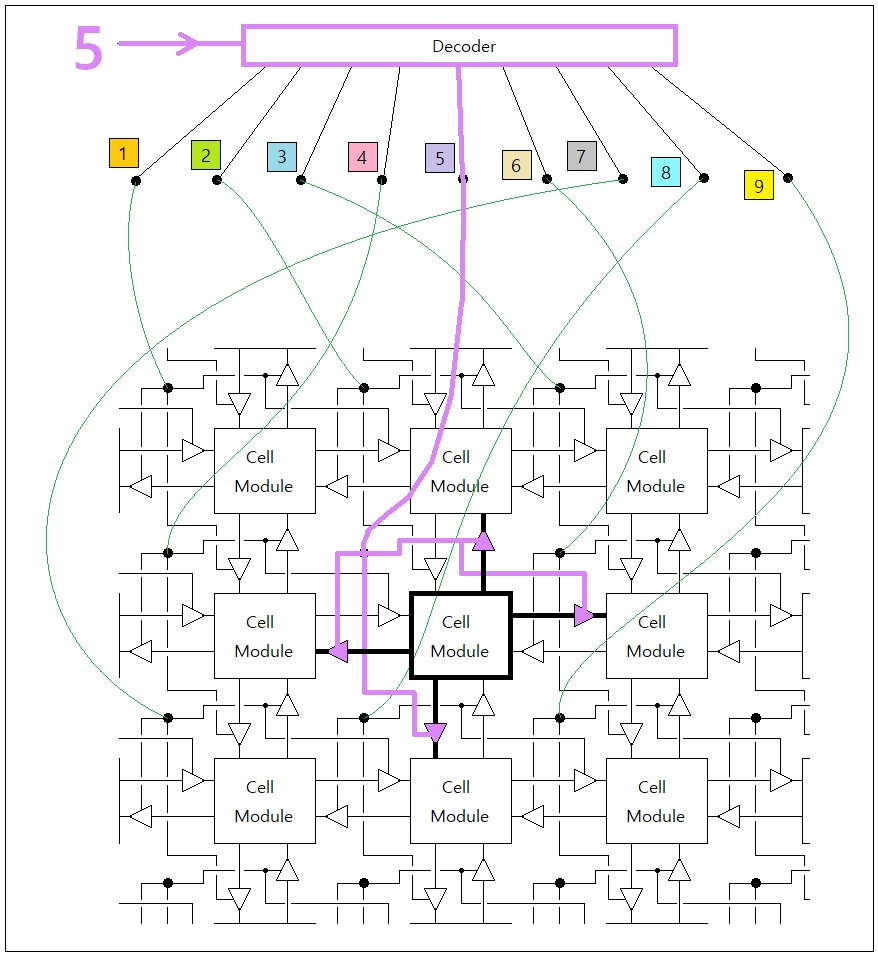

For a more optimized implementation, we will need a piece of customized hardware which is designed like the one shown below. Here, the system enters the index of the parallel-execution mode as the input parameter, and the hardware uses that index to activate only 1 out of 9 groups of cells and their neighboring update-command ports. Each "cell module" has its own logic processor which determines the future state of itself and its neighbors, based upon the current state of itself and its neighbors.

Previous Page

Next Page

Previous Page

Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service