Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 14, 2024

This is Part 14 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

So far, I have demonstrated quite a variety of game mechanics and how they could be designed in the language of Prolog. I have not yet, however, carefully dealt with the matter of optimization in this subject.

Those of you who have learned the basics of Prolog, or logic programming in general, would have realized that a program which is based upon logical relations does not necessarily run efficiently unless we take extra precautions on how it is being implemented. A standard Prolog application, for example, is not so computationally elegant in the sense that it is prone to perform exhaustive searching and pattern matching of relations in order to find the right answer to a query.

A typical Prolog system, unless it is provided with clever algorithmic shortcuts, exhibits a tendency to solve problems by means of recursive tree search, which is reminiscent of initiating a tree of function calls but more "comprehensive" in the sense that it often needs to force itself to traverse all the alternative pathways via which a solution could be derived.

Whereas a function only requires the system to apply the given parameters to the body of the expression and return the result of evaluation, a logical statement (such as a horn clause) requires the system to come up with every possible permutation of parameters which could manifest themselves to a valid answer. And the process of searching for all such possibilities can oftentimes waste a great deal of computational resources, both in terms of time and space.

In order to create a fairly efficient gameplay system based off of the language of Prolog, therefore, we better abandon the notion of simply letting Prolog take care of the given set of rules based upon its default mode of computation.

Instead, we ought to reimagine the language from the ground up and curtail any of the overgeneralized parts of its core algorithm, so as to specialize the engine of logic to fit our needs. This will help us optimize the system, letting it update the in-game relations (e.g. actors, events, etc) without going on a roundabout of unnecessary searching steps.

(Note: You may as well imagine this as a process of designing a zombie apocalypse game. Zombies do not require highly advanced pathfinding algorithms such as A-star, so we will end up wasting tons of computational power if we simply assume that every game character should be equipped its own A-star pathfinding behavior. This means that we can optimize our game by getting rid of such a superfluous form of intelligence. Likewise, we can optimize the way in which our Prolog system runs by getting rid of superfluous computational steps.)

So, let us start implementing the engine of Prolog from scratch, rather than simply grabbing its standard interpreter and using it for granted.

First of all, we all know that this language comprises a list of rules (i.e. horn clauses), each of which in turn comprises a list of relations. Whenever the program tries to see if a rule holds, it attempts to figure out a set of arguments which satisfy all the relations on the right-hand side of the rule. For a quick demonstration, let me give you a couple of examples of how this may work.

What is displayed below is the simplest case I could come up with. It does not yet involve any argument whatsoever, which makes answer-finding extremely straightforward. The only thing that the system needs to do is look up the list of facts and verify that the required ones are present.

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy.

RULES:

humid :- rainy.

------------------------------The above rule says that, if the weather is rainy, it must be humid as well. We can easily imagine that the application will look at this rule, check to see if the fact "rainy" is available, and integrate "humid" as another fact if so. Since "rainy" is a fact, "humid" will be a fact, too.

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy.

RULES:

humid :- rainy.

---------- Time = 1 ----------

FACTS:

rainy.

humid.

RULES:

humid :- rainy.

------------------------------Let me add another rule which states that the weather is obnoxious as long as it is both humid and hot. Also, I have added a new initial fact called "hot" here, which means that one of the conditions is already met.

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy.

hot.

RULES:

humid :- rainy.

obnoxious :- humid, hot.

------------------------------We can imagine that the Prolog interpreter will scan the first rule and conclude that "humid" must be listed as a fact because the weather is rainy. After doing that, it will scan the second rule and conclude that "obnoxious" should also be included as a fact because both "humid" and "hot" can be found within the list of facts.

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy.

hot.

RULES:

humid :- rainy.

obnoxious :- humid, hot.

---------- Time = 1 ----------

FACTS:

rainy.

hot.

humid.

obnoxious.

RULES:

humid :- rainy.

obnoxious :- humid, hot.

------------------------------What if the two rules were ordered differently, like the ones shown below?

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy.

hot.

RULES:

obnoxious :- humid, hot.

humid :- rainy.

------------------------------In this case, too, the result will be the same. I will tell you why.

When the interpreter scans the first rule, it will first try to find out if "humid" is a fact. Since "humid" is not explicitly listed as a fact yet, the interpreter will search for a rule from which "humid" could be inferred as a fact (This is plan B). And, voila! There indeed is such a rule; it is the second entry in the list of rules (i.e. "humid :- rainy.").

In this second rule, we can clearly see that "humid" must be a fact if "rainy" is a fact. So the interpreter will look up the list of facts and instantly be able to tell that "rainy" is definitely present in it, which qualifies it as a fact. Thus, "humid" will be included as a fact.

After making such a conclusion, the interpreter will go back to the original rule (i.e. "obnoxious :- humid, hot."), this time with the knowledge that "humid" is a fact. This implies that the first predicate (i.e. "humid") is satisfied, so the system will proceed to take a look at the second one, which is called "hot".

Is "hot" a fact? Oh yes, it is listed as one of the available facts. Since both "humid" and "hot" turned out to be facts, Prolog will conclude that "obnoxious" must also be a fact. So it will put "obnoxious" in the list of facts.

Having finished scanning the first rule, it will proceed to scan the second rule. But then, the goal of the second rule (i.e. "humid :- rainy.") is to figure out what makes "humid" a fact. Well! It already is listed as a fact, so we shouldn't even bother to evaluate this rule once again just to repeatedly verify its truthfulness. So, we will skip this one and wrap up the current clock cycle because there is no more rule to scan.

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy.

hot.

RULES:

obnoxious :- humid, hot.

humid :- rainy.

---------- Time = 1 ----------

FACTS:

rainy.

hot.

humid.

obnoxious.

RULES:

obnoxious :- humid, hot.

humid :- rainy.

------------------------------It's been pretty easy-going so far. You see, the Prolog environment only needs to keep track of two lists of data - one for the facts which have been identified so far, and the other one for rules which are to be scanned for the purpose of deriving new facts out of old ones.

In general, we should expect the system to scan the entire list of rules during each time step (i.e. clock cycle) and add the acquired facts to the list of existing facts, while discarding ones that are considered obsolete. Our previous example did not involve the removal of any of the existing ones (because none of them could be considered obsolete at any given moment in time), yet we will see instances of such an action later on.

Let me provide you with a slightly more complex example. This time, the relations will be carrying arguments in them (See the code below).

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy(seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

RULES:

humid(City) :- rainy(City).

humid(City2) :- rainy(City1), near(City1, City2).

------------------------------Observe the list of facts which are initially given. The first one says that Seattle is a rainy city, and the second one says that Bellevue is a city located nearby Seattle.

Aside from the list of facts, we have the list of rules. The first rule tells us that if a city is rainy, it must be humid as well. The second rule states that a city which is nearby a rainy city must be considered humid as well.

Let's run our imaginary Prolog interpreter once again, and see what kinds of facts shall be derived from this initial set of definitions. First, it will take a look at the first rule (i.e. "humid(City) :- rainy(City)"), and ask itself:

"All right. I would like to know if 'humid(City)' can be included in the list of facts. In order to figure it out, I must first know which values of 'City' will enable 'humid(City)' to become a fact. I already know that these values are the ones which, when plugged into the rule, will qualify all the relations on the right-hand side as facts."

Thus, it will scan the right-hand side and realize that it only contains one relation, "rainy(City)", which implies that "humid(City)" will be a fact for any value of "City" which makes "rainy(City)" a fact.

To find out such values, the interpreter will first look up the list of facts, and immediately notice that "rainy(seattle)" is already listed as one of the given facts. It means that setting the value of "City" to "seattle" will make "rainy(City)" a fact, which in turn will make "humid(City)" a fact according to the first rule. Therefore, the conclusion will be that "humid(seattle)" must be declared as a fact, meaning that it ought to be included in the list of facts.

FACTS:

rainy(seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

humid(seattle).Since there is no other value of "City" which can be applied to the first rule, the system will then simply move on to the second rule.

The second rule says that a city is humid if it is nearby a rainy city. Such a city should refer to any value of "City2" which satisfies both "rainy(City1)" and "near(City1, City2)".

Let us solve the first relation. Which values of "City1" make "rainy(City1)" a fact? From the list of facts, we can instantly tell that "seattle" is the only "City1" which maps into an existing fact (i.e. "rainy(seattle)"). From the list of rules, we can tell that there is no rule from which a fact of type "rainy" can be derived (In other words, there is no horn clause whose left-hand side begins with the word "rainy"). Therefore, we know that "seattle" is the only possible value to which "City1" can be bound.

If we substitute "City1" with "seattle", then, the rule will appear like this:

humid(City2) :- rainy(seattle), near(seattle, City2).We know that "rainy(seattle)" is a fact. The only remaining task is to find a value of "City2" which will make "near(seattle, City2)" a fact. What would that be?

Again, we will look back at the list of facts, and try to gather all the existing facts which begin with the word "near". Obviously, "near(seattle, bellevue)" is the only fact in this list which meets such a criterion. Since the second argument of "near(City1, City2)" is what "bellevue" is supposed to represent, we will bind the value of "City2" to "bellevue". This will result in the following set of substitutions:

humid(bellevue) :- rainy(seattle), near(seattle, bellevue).Okay! Since "rainy(seattle)" and "near(seattle, bellevue)" are both listed as facts, the interpreter is now able to conclude that this rule holds as long as "City1" is bound to "seattle" and "City2" is bound to "bellevue", hence that "humid(bellevue)" must be included as yet another fact under such a set of bindings.

FACTS:

rainy(seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

humid(seattle).

humid(bellevue).Now that the system has gone over all the listed rules (i.e. both the first and the second), it will terminate the current clock cycle and increment the time step by 1. The following record, therefore, will be the result of all the tasks which were carried out during the first time step (n = 0).

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy(seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

RULES:

humid(City) :- rainy(City).

humid(City2) :- rainy(City1), near(City1, City2).

---------- Time = 1 ----------

FACTS:

rainy(seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

humid(seattle).

humid(bellevue).

RULES:

humid(City) :- rainy(City).

humid(City2) :- rainy(City1), near(City1, City2).

------------------------------For the sake of designing a gameplay system as opposed to a mere answer-finder, though, we need to have temporal relations (aka "events") - that is, relations which belong to certain points in time, instead of existing timelessly as though they are pure ideas such as mathematical theorems, laws of nature, etc.

Just like I had mentioned during the early parts of the series (e.g. Part 2 and Part 3), time plays a crucial role in the design of video games. It is because the concept of time is indispensable in a system which is driven by a sequence of events.

Many things happen inside a game, such as gunshots, explosions, births, deaths, and plenty of others. They can all be classified as "events", and events belong to certain points in time, as opposed to static facts which are considered "true" regardless of at which moment in time they are being asserted.

Unlike a timeless fact which does not possess a time parameter, an event is a time-dependent fact which is only "true" at a specific time step. An event called "gunshot[8]", for instance, is a gunshot which occurred only at time 8 and nowhere else on the timeline. If gunshots happened during three consecutive time steps, we would have to list three separate events which belong to three consecutive time steps such as: "gunshot[8], gunshot[9], gunshot[10]".

Since the vast majority of facts inside a video game are time-dependent in nature (i.e. they are "events" instead of pure ideas), we will definitely need to make sure that the Prolog interpreter is capable of handling relations which have time parameters in them.

So, here is an example:

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy[0](seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

RULES:

humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City).

humid[n](City2) :- rainy[n-1](City1), near(City1, City2).

------------------------------This one looks the same as the previous scenario, except that now the "rainy" and "humid" relations are bound to specific points in time.

A city which was raining at one moment in time is not necessarily rainy at another moment in time. Also, a city which was humid at one moment in time is not necessarily humid at another moment in time. This is why, in our updated example, facts concerning raininess or humidity of the cities are equipped with their own temporal offsets. On the other hand, the "near" relation is considered timeless because two nearby cities won't stop being nearby any time soon.

Let us analyze both the initial list of facts as well as the initial list of rules. The first given fact says "rainy[0](seattle)". This means that the city of Seattle was rainy at time 0. We can never be sure, based upon this fact alone, that Seattle will stay rainy at time 1, 2, 3, or else, but at least we can absolutely be sure that it was rainy at time 0.

The second fact, "near(seattle, bellevue)", simply states that Seattle and Bellevue have been close to each other, and will stay being close to each other forever. This fact, therefore, is timeless in the sense that its truth is eternal; it has been true all the time, and it shall stay true as long as we are alive to witness the passage in time.

What about the rules? The first rule claims that a city which is currently rainy must also be humid at the same time. The second rule says, on the other hand, that a city which is nearby a rainy city will become humid not immediately, but after a delay of 1 time step (Another way of putting it would be: "If a city was rainy during the previous time step, its neighboring cities will become humid during the current time step."). Recall that "n" refers to the current time.

The Prolog system will begin scanning this initial set of information, starting at time 0.

First, we can expect the interpreter to read the first rule and stumble upon the time parameter "n". As I just mentioned, "n" indicates the current time, which is 0. So we will first substitute all the "n"s in this rule with the value of 0, which yields:

humid[0](City) :- rainy[0](City).Okay, now we know the exact point in time to which the associated facts ("humid" and "rainy") should belong. What else? Just like it was illustrated in the previous example, the interpreter will need to first look up the list of given facts to see if there are facts which correspond to the ones on the right-hand side of the rule (i.e. "rainy[0](City)").

And, you guessed it right. There is a fact called "rainy[0](seattle)", whose type ("rainy") and time (0) both match the ones on the right-hand side's relation which is "rainy[0](City)". This leads to the following substitution:

humid[0](seattle) :- rainy[0](seattle).... which leads to the derivation of a new fact called "humid[0](seattle)". This makes sense because the rule says that if a city is rainy, it must simultaneously be humid. Since Seattle was rainy at time 0, we must be able to tell that Seattle was also humid at time 0.

FACTS:

rainy[0](seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

humid[0](seattle).Let's move on to the second rule. This rule states that in order for "humid[n](City2)" to be a fact, both "rainy[n-1](City1)" and "near(City1, City2)" must be evaluated as facts.

Before investigating these two requisite conditions, let us first substitute all the instances of "n" in this rule with the current time value (0). If we do that, the rule will look like this:

humid[0](City2) :- rainy[-1](City1), near(City1, City2).The goal of the interpreter is to find the specific values of "City1" and "City2" which will turn both "rainy[-1](City1)" and "near(City1, City2)" into facts. Let me start with the first relation, "rainy[-1](City1)".

Let us take a look at the list of facts. Does any of the given facts begin its expression with "rainy[-1]"? No, absolutely not. There is a fact called "rainy[0](seattle)", yet it only tells us about the raininess of the city at time 0, not time -1. There is no given fact which explicitly shows us which city was rainy at time -1.

Since we cannot find a possible candidate of "rainy[-1](City1)", let us take a look at the other rules, for the hope of being able to derive a fact which may begin with "rainy[-1]". Unfortunately, none of the rules provides us with a way to infer a new fact of type "rainy" (i.e. None of the horn clauses begins its left-hand side with the word "rainy").

Since neither the list of facts nor the list of rules gives us a method of finding a fact which corresponds to the format "rainy[-1](...)", the right-hand side of the second rule (i.e. "humid[0](City2) :- rainy[-1](City1), near(City1, City2)") can never be satisfied during time 0, which implies that we are unable to derive a fact of form "humid[0](City2)" from this rule during the current clock cycle.

Now that there is no more rule to evaluate, the interpreter should stop at this moment and wrap up the current time frame. The updated list of facts will then be carried over to the next time step (n = 1), like the one displayed below:

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy[0](seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

RULES:

humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City).

humid[n](City2) :- rainy[n-1](City1), near(City1, City2).

---------- Time = 1 ----------

FACTS:

rainy[0](seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

humid[0](seattle).

RULES:

humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City).

humid[n](City2) :- rainy[n-1](City1), near(City1, City2).

------------------------------The new time step is now here to commence. The current time is now 1, instead of 0. The list of facts contains one extra fact called "humid[0](seattle)", which was something that the interpreter derived during the previous time step (n = 0). Other than that, everything else stays the same.

Now that the new clock cycle has begun, the system will of course have to repeat what it did before. It wlll begin scanning the list of rules. Let's see, what is the first rule in the list? Oh, it is: "humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City)". Let us substitute all of its "n"s with the current time step (i.e. 1). This will give us:

humid[1](City) :- rainy[1](City).The next step is to evaluate the right-hand side of the rule to see if the rule can be satisfied. Does any of the given facts begin with "rainy[1]"? No. There indeed is a fact which begins with "rainy[0]", but it only tells us which city was rainy during the previous time step. It does not tell us which city is rainy right now, at the present moment (n = 1). Thus, no fact of the form "humid[1](City)" can be derived from this rule.

What about the second rule? Again, we should first substitute its time parameters with their appropriate values. The result will then look like this:

humid[1](City2) :- rainy[0](City1), near(City1, City2).Here, we are seeing something recognizable. One of the listed facts is "rainy[0](seattle)", which means that this rule might be satisfied if we bind the value of "City1" to "seattle". Keeping this in mind, let us proceed to the next relation called "near(City1, City2)".

Once more, we will look up the list of facts and try to see if any of them has the same format as "near(City1, City2)". And, indeed! There is a fact called "near(seattle, bellevue)", which also happens to expect us to bind the value of "City1" to "seattle". We are lucky in this case because such a binding already exists and does not introduce any contradiction. Meanwhile, it also expects us to bind "City2" to "bellevue" in order to make "near(City1, City2)" a fact. So, let us do that as well.

And guess what? As soon as we bind "City1" to "seattle" and "City2" to "bellevue", we are left with the following expression:

humid[1](bellevue) :- rainy[0](seattle), near(seattle, bellevue).Since both "rainy[0](seattle)" and "near(seattle, bellevue)" are listed as facts, we now have the right to assert that "humid[1](bellevue)", the left-hand side of the horn clause, must be considered a fact as well.

FACTS:

rainy[0](seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

humid[0](seattle).

humid[1](bellevue).There are no more rules to look at, so our process of deriving new facts in this current time frame is over. Now that we are also dealing with this new concept called "passage in time", however, we must also do our job of getting rid of facts which have become obsolete due to their old age.

A timeless fact (i.e. a fact without a time parameter) is destined to stay forever; its truth is everlasting, and no matter how much time passes by, it will always remain in our list of facts.

A fact which belongs to a certain point in time, on the other hand, is only true within the context of the given time step. For example, the fact called "rainy[0](seattle)" describes an event which occurred at time 0. Thus, we can guarantee that this particular fact will not be referenced if none of the rules happen to refer to any of the events which occurred at time 0.

Let us take a look at the list of rules:

RULES:

humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City).

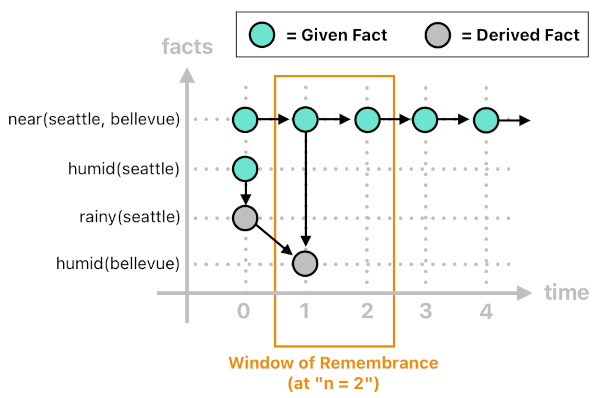

humid[n](City2) :- rainy[n-1](City1), near(City1, City2).If you just look at the right-hand sides of the two given rules, you will realize that the most distant point in the past that any of these rules will ever happen to access is "n-1", which is one step back in time. This means that the rules will never have to look up a fact which is older than "n-1".

Up until time 1, we have been listing "rainy[0](seattle)" as a fact because, if the current time is 1 (i.e. n = 1), the relation "rainy[n-1](City1)" will definitely require us to observe a fact of type "rainy" at time 0 (since 1-1 = 0). So, we know that "rainy[0](seattle)" will still be used at time 1. The same logic applies to other available facts, such as "humid[0](seattle)".

However, the interpreter is now wrapping up this time step (n = 1) and is about to move on to the next time step (n = 2). When time step 2 begins, will any of the facts which belonged to time 0 still be referenced for the purpose of deriving new facts? Absolutely not! None of the events which occurred at time 0 will be used anymore, since 1 (= 2-1) is now the most distant point in the past that the rules will ever be looking back.

This means that both "rainy[0](seattle)" and "humid[0](seattle)" will be obsolete as soon as the current time becomes 2. So, let us make our interpreter get rid of them from the list of facts, leaving only the other two:

FACTS:

near(seattle, bellevue).

humid[1](bellevue).Once this cleanup process is over, the system can then proceed to the next time step (n = 2).

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy[0](seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

RULES:

humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City).

humid[n](City2) :- rainy[n-1](City1), near(City1, City2).

---------- Time = 1 ----------

FACTS:

rainy[0](seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

humid[0](seattle).

RULES:

humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City).

humid[n](City2) :- rainy[n-1](City1), near(City1, City2).

---------- Time = 2 ----------

FACTS:

near(seattle, bellevue).

humid[1](bellevue).

RULES:

humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City).

humid[n](City2) :- rainy[n-1](City1), near(City1, City2).

------------------------------Okay, here is the same cycle all over again. The system will scan the rules one by one, derive new facts from the given lists (based on the latest time step, which is 2), delete obsolete facts, and then move on to the next time step, go over the same cycle again, again, and again, etc.

We are able to tell that, at time 2, no more facts can possibly be inferred from any of the given rules. Both of the two rules require a fact of type "rainy" to exist, yet we can clearly see that none of the listed facts is of type "rainy". Also, we have no rule from which a new fact of type "rainy" is capable of being instantiated, either. Thus, none of the rules will be satisfied and no more fact is going to emerge.

What about obsolete facts? Now that the current time has been incremented to 2, we must once again inspect the list of facts and check to see if any of them has become obsolete.

"near(seattle, bellevue)" is timeless, so we should just skip over it (because we know it will never become obsolete). How about "humid[1](bellevue)"? Since none of the right-hand sides of the rules references an event of type "humid" which occurred at a point in time that is less than or equal to 1, we know that this particular fact has now become obsolete. So, we can wipe this out of the list, leaving only "near(seattle, bellevue)" and nothing else.

FACTS:

near(seattle, bellevue).This will lead to the following history of facts, their births, and their deaths:

---------- Time = 0 ----------

FACTS:

rainy[0](seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

RULES:

humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City).

humid[n](City2) :- rainy[n-1](City1), near(City1, City2).

---------- Time = 1 ----------

FACTS:

rainy[0](seattle).

near(seattle, bellevue).

humid[0](seattle).

RULES:

humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City).

humid[n](City2) :- rainy[n-1](City1), near(City1, City2).

---------- Time = 2 ----------

FACTS:

near(seattle, bellevue).

humid[1](bellevue).

RULES:

humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City).

humid[n](City2) :- rainy[n-1](City1), near(City1, City2).

---------- Time = 3 ----------

FACTS:

near(seattle, bellevue).

RULES:

humid[n](City) :- rainy[n](City).

humid[n](City2) :- rainy[n-1](City1), near(City1, City2).

------------------------------No more explanation will be necessary at this point. The interpreter will proceed to time step 4 and try to derive new facts, but fail once again. No existing fact will be thrown away either, since the only thing in the list is "near(seattle, bellevue)". This frozen state will stay as it is forever, no matter how much time passes by. This is the "heat death" of the system.

(Will be continued in Part 15)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service