Author: Youngjin Kang Date: September 29, 2024

This is Part 9 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

Last time, I talked about the things we can do at the moment of an actor's birth (or death). As soon as an actor comes into existence, for example, we are able to define its own set of characteristics which are promised to last as long as it lives. Each characteristic is basically a sequence of events which keeps growing, up until the point at which the actor dies.

This time, I will be talking about things which may happen during an actor's course of life. Besides spawning and despawning, an actor must also be capable of "changing" itself in some way or another while it is alive, unless it is an idle being which never interacts with anything outside of itself.

Whenever an actor interacts with something external, it is usually expected to undergo some kind of transformation. What kind? There are many, and I am here to illustrate how to implement transformative events in the language of Prolog.

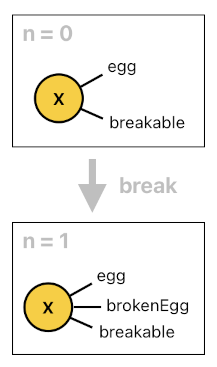

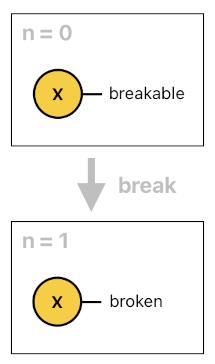

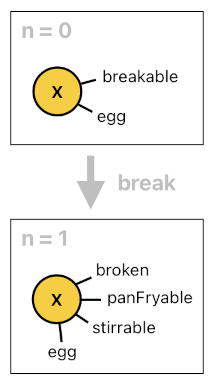

If you remember the egg analogy from the last article, you will be able to recall that the system should be able to convert an egg into a broken egg with the help of the "break" event. Since an egg is breakable, we can break it. And whenever we break it, it transforms into a broken egg (i.e. The tag "brokenEgg" gets assigned to it).

breakable(X) :- egg(X).

brokenEgg[n](X) :- egg[n-1](X), breakable[n-1](X), break[n-1](X).

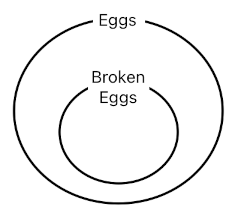

Here is something fishy, though. Even after we break an egg and turn it into a broken egg, it should still be considered an "egg" because breaking it does not disqualify it from being an egg. Mathematically speaking, the set of broken eggs is a subset of the set of all eggs.

And of course, this is exactly what we are presuming in the rules above. When we assign the tag "brokenEgg" to X, we are not removing the tag "egg" from it because a broken egg is still an egg. An egg may or may not be a broken egg, but a broken egg is always an egg.

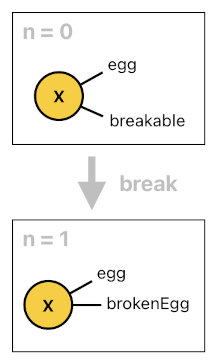

The problem is that, once an egg gets broken, it should no longer be breakable. So the first horn clause, "breakable(X) :- egg(X)", won't work for broken eggs; it will simply allow broken eggs to be broken again and again, which is a nonsense.

Thus, we are required to explicitly state that an egg is breakable only if it is NOT a broken egg. The following code is the result of such modification:

breakable[n](X) :- egg[n](X), !brokenEgg[n](X).

brokenEgg[n](X) :- egg[n-1](X), breakable[n-1](X), break[n-1](X).

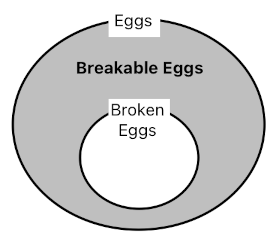

From the perspective of set theory, one may as well explain this logic by saying that a breakable egg is an element of the set of all eggs MINUS the set of broken eggs. The first of the two rules above, therefore, could be considered an instance of set operation (i.e. "breakableEggs" = "eggs" - "brokenEggs").

Now, one might question the necessity of having the "breakable" tag in our code. Why not just directly embed the egg's condition of breakability right inside the second horn clause, like the one displayed below? This way, we will be able to get rid of the word "breakable" entirely, thereby making the code a bit more succinct.

brokenEgg[n](X) :- egg[n-1](X), !brokenEgg[n-1](X), break[n-1](X).This is a valid way of implementing the system. However, we should also be aware of the fact that eggs are not the only things which may be breakable. Suppose that there is some sort of generic "breaker" in our game, which has a tendency of breaking any breakable object it happens to touch. In such a case, we would like to label any breakable object with the word "breakable", so that the only thing that the breaker will need to do is check the presence of the word "breakable" in whichever actor it encounters, and proceed to break it if so (See the following code).

break[n](Y) :- breaker[n-1](X), breakable[n-1](Y), collide[n-1](X, Y).

breakable[n](X) :- egg[n](X), !brokenEgg[n](X).

breakable[n](X) :- window[n](X), !brokenWindow[n](X).

breakable[n](X) :- bottle[n](X), !brokenBottle[n](X).

brokenEgg[n](X) :- egg[n-1](X), breakable[n-1](X), break[n-1](X).

brokenWindow[n](X) :- window[n-1](X), breakable[n-1](X), break[n-1](X).

brokenBottle[n](X) :- bottle[n-1](X), breakable[n-1](X), break[n-1](X).This is a bit ugly, though. Here, we are introducing a bunch of new terminologies, such as "brokenEgg", "brokenWindow", "brokenBottle", and so forth, just for the sake of making a distinction between the broken states and not-broken states of a bunch of objects. If there are 100 types of breakable entities, this kind of coding practice will force us to come up with 100 new words (which all begin with "broken(...)") as well as 200 new horn clauses just to take account of their breakability.

There is a pretty neat solution to this, fortunately. Instead of assigning a distinct tag to each actor's broken state (such as "brokenEgg"), we may simply choose to assign a generic tag called "broken" to any actor which is considered broken. The "breakable" predicate, then, will only need to set itself to TRUE when the actor has been breakable but NOT been broken recently. The following code demonstrates how this logic works.

breakable[n](X) :- egg[n](X), spawnTime[n](X, n).

breakable[n](X) :- window[n](X), spawnTime[n](X, n).

breakable[n](X) :- bottle[n](X), spawnTime[n](X, n).

breakable[n](X) :- breakable[n-1](X), alive[n-1](X), !broken[n](X).

broken[n](X) :- breakable[n-1](X), break[n-1](X).

broken[n](X) :- broken[n-1](X), alive[n-1](X).

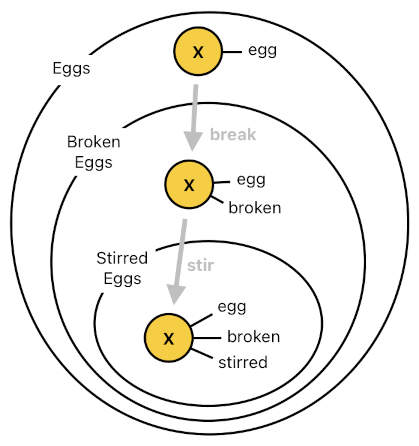

Instead of "brokenEgg", we now have an "egg" which can optionally be labeled as "broken" depending on whether it has been broken or not. The composition of the two words, "egg" and "broken", implies that the object is a broken egg. The absence of the latter implies that the egg has not been broken yet.

As you can clearly see in the code above, the only type-specific rules (i.e. the ones which have to be repeated for different types of actors) are ones responsible for initializing the "breakable" tag for all object types which are considered initially breakable. The state of being breakable, then, will persist as long as the object to which it is bound is neither dead nor broken. The state of being broken, too, will persist in a similar manner.

The overall idea is to use multiple tags to represent an actor, instead of just one. In other words, we may as well claim that the current state of an actor is the combination of all the tags it happens to possess right now.

For the case of an egg, for instance, we could say that:

(1) A default egg (That is, a plain raw egg which has just been laid by a chicken) is an actor with one state-related tag called "egg",

(2) A broken egg is an actor with two state-related tags called "egg" and "broken", and

(3) A stirred egg is an actor with three state-related tags called "egg", "broken", and "stirred" (because an egg must first be broken in order to be stirred),

... and so on.

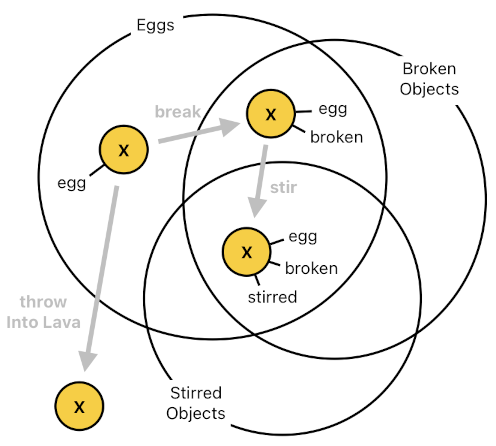

A state transition of an actor, then, can be interpreted as a process of reconfiguring the actor's inventory of tags. The event of breaking the egg, for example, resulted in attaching an additional tag called "broken" to the egg but did not take away any of its existing tags. If the event were something really extraordinary such as "throwIntoLava", the system would have removed the tag "egg" from the actor because no egg is capable of maintaining its identity as an egg despite being exposed to such an extreme circumstance.

From the viewpoint of set theory, an actor's state transition (i.e. addition/removal of tags) may as well be thought of as a displacement of the actor's "conceptual location" from one set to another. The act of breaking an egg, for example, will put it inside the intersection of two sets - eggs and any broken objects. The act of throwing an egg into lava, on the other hand, will put it outside of the set of eggs entirely.

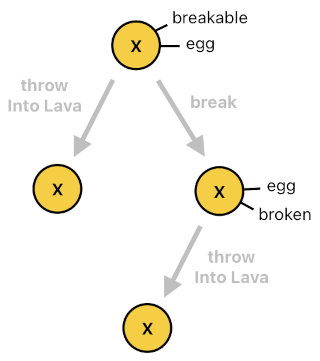

What's interesting is that there are alternative ways in which an actor may be transformed, some of which are mutually exclusive with one another. Once you throw an egg into lava, for instance, you cannot break it later on because it will no longer be an egg (Instead, it will perhaps be a morsel of ash, which is definitely not breakable). But if you break the egg first, you will still be able to throw it into lava and turn it into ash-omelet. Thus, we may conclude that the "throwIntoLava" event excludes the "break" event from occurring, while the "break" event does NOT exclude the "throwIntoLava" event from occurring.

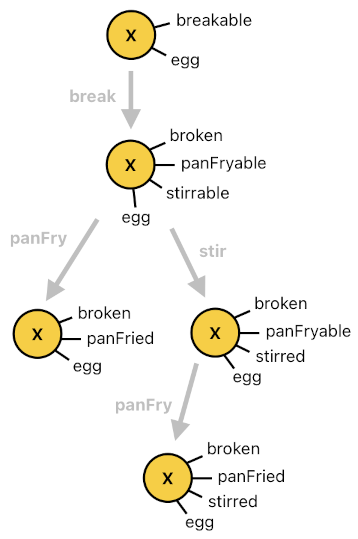

The reason why this sort of distinction exists is that the current state of an actor is basically a node in a graph (aka "state transition diagram"), in which each node is one of the actor's possible states and each directed edge is an event which triggers a transition from one state to another.

Let me come up with a more interesting example which contains two alternative choices of actions - pay-frying and stirring (You may recall them from the previous article, in which their definitions were left incomplete).

The most intriguing aspect of these two choices is that choosing one of them prevents the other one from taking place, thus rendering two alternative pathways (in space space) through which the egg can travel. In order to explain why this is so, I will first come up with a number of rules which will eventually lead to such a scenario.

The two clauses below are what one may refer to as "enablers"; they are responsible for enabling the egg to be either pan-fried or stirred, the very moment the egg gets broken. An egg which has NOT yet been broken is neither pan-fryable nor stirrable.

payFryable[n](X) :- egg[n-1](X), break[n-1](X).

stirrable[n](X) :- egg[n-1](X), break[n-1](X).

After the initial moment of enablement, of course, the system should let the broken egg stay pan-fryable and stirrable unless some change takes place. The following two rules ensure that anything which is pan-fryable will stay pan-fryable until it either gets destroyed or pan-fried, as well as that anything which is stirrable will stay stirrable until it either gets destroyed, stirred, or pan-fried (because the process pan-frying solidifies the object, thus preventing it from being stirred).

panFryable[n](X) :- panFryable[n-1](X), alive[n-1](X), !panFried[n](X).

stirrable[n](X) :- stirrable[n-1](X), alive[n-1](X), !stirred[n](X), !panFried[n](X).The presence of the "!panFried[n](X)" predicate in the second rule implies that pan-frying blocks the subsequent stirring of the object, while the absence of the "!stirred[n](X)" predicate in the first rule implies that stirring does NOT block the subsequent pay-frying of the object.

When an actor is pan-fryable, we can pan-fry it by attaching the tag "panFried" to it; once pan-fried, the actor will stay pan-fried as long as it exists. And when an actor is stirrable, we can stir it by attaching the tag "stirred" to it; once stirred, the actor will stay stirred as long as it exists. The code below shows how these lines of logic could be implemented in Prolog.

panFried[n](X) :- panFryable[n-1](X), panFry[n-1](X).

panFried[n](X) :- panFried[n-1](X), alive[n-1](X).

stirred[n](X) :- stirrable[n-1](X), stir[n-1](X).

stirred[n](X) :- stirred[n-1](X), alive[n-1](X).Furthermore, here is how the act of either pan-frying or stirring might be initiated (See the code below). Whenever a heated pan encounters an actor which is marked as "payFryable", the pan will pan-fry it (i.e. attach the tag "panFried" to it), thus preventing it from being stirred afterwards (or being pan-fried twice). And whenever an oscillating stirrer encounters an actor which is marked as "stirrable", the stirrer will stir it (i.e. attach the tag "stirred" to it), thus preventing it from being stirred twice.

panFry[n](Y) :- pan[n-1](X), heated[n-1](X), panFryable[n-1](Y), collide[n-1](X, Y).

stir[n](Y) :- stirrer[n-1](X), oscillating[n-1](X), stirrable[n-1](Y), collide[n-1](X, Y).And of course, sometimes we feel the necessity to indicate each unique combination of the actor's tags with a single term. An egg which has been stirred and pan-fried, for example, would be referred to as an omelet, whereas an egg which has been pan-fried WITHOUT being stirred would just be referred to as a fried egg.

omelet[n](X) :- egg[n](X), stirred[n](X), panFried[n](X).

friedEgg[n](X) :- egg[n](X), !stirred[n](X), panFried[n](X).(Will be continued in Part 10)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service