Author: Youngjin Kang Date: September 24, 2024

This is Part 8 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

In the last article, I demonstrated how to spawn brand new actors (objects) out of nowhere, with the help of a unique ID generation algorithm. I have not, however, yet explained how to initialize the properties of a dynamically spawned actor.

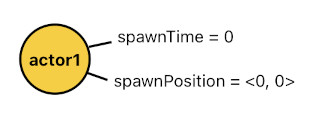

You may recall that there are attributes which must be available to let us know the actor's exact time and place of birth. One of them is "spawnTime", and the other one is "spawnPosition". The following two predicates reveal us, for example, that an actor called "actor1" was born at time 0 and at position <0, 0>.

spawnTime(actor1, 0).

spawnPosition(actor1, <0, 0>).

And since these two predicates are not bound to a specific point in time (i.e. they do not have time parameters, such as "[n]"), we know that both the spawn-time and spawn-position of "actor1" will be fully exposed to the rest of Prolog's environment throughout the entirety of time.

Such a static and timeless way of defining an actor's properties, though, cannot be used for those which have been spawned dynamically. We cannot pre-define their spawn-times and spawn-positions explicitly in the source code itself, since we can never be sure beforehand exactly when and where they are going to spawn, as well as what their IDs are going to be, while the game is running.

Each of the properties of a dynamically allocated actor, therefore, must be modeled as a sequence of events which gets created when the actor spawns, and gets destroyed when the actor despawns.

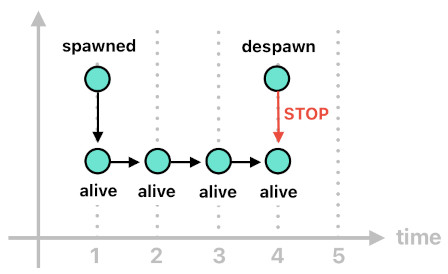

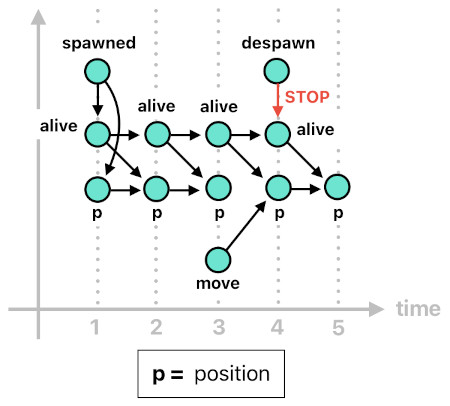

The most rudimentary of them is the special attribute called "alive", which tells us whether the actor is still living or not. The presence of "alive[n](Id)", for instance, will signal that the actor whose identifier is the value of "Id" must be alive at time "n" (or dead otherwise).

The two rules listed below defines such a relation, the first of which is the base case and the second one is the recursive case. First of all, we know that an actor must be alive the very moment it comes into existence (i.e. when its "spawned" event kicks off). After this initial moment of birth, we know that the actor will stay alive as long as the "despawn" event does not occur. Think of "despawn" as a signal which orders the given actor (Id) to stop existing.

alive[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, Cause, Pos).

alive[n](Id) :- alive[n-1](Id), !despawn[n-1](Id).

With this "alive" attribute, we are now free to define numerous other properties which are supposed to persist only during the actor's lifetime. All we need to do is represent them as chains of events which last only as far as the actor's "alive" event keeps firing itself.

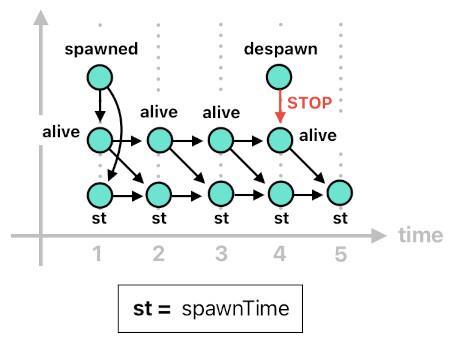

Let us start with "spawnTime". The moment the actor spawns, we know that the current time (denoted by "n") must be the time at which the actor was born. Thus, the time (n) to which the "spawned" event belongs should be defined as the actor's spawn time.

The thing is, I am now obliged to include the time notation ("[n]") in the "spawnTime" relation. This is because a dynamically created actor's "spawnTime" is meant to be defined only while it is alive. Defining it before the actor's birth is a nonsense because it would imply that the relation predicted exactly when the instance of birth would take place beforehand. Defining it after the actor's death is not so sensible either, since it is wasteful (from a performance point of view) to let obsolete properties linger and accumulate as time passes by, allowing more and more actors to die and leave their ghostly remnants which are permanently stuck in the overworld.

Thus, it should make sense to ensure that an actor whose time of birth is determined during the game's runtime must have its "spawnTime" relation only exist as long as the actor itself exists.

The two rules below illustrate how this can be achieved. The first one initializes the first "spawnTime" event the moment the actor comes into existence (This is the beginning of the chain reaction). The second rule, then, keeps reproducing the "spawnTime" event over and over, up until the point at which the actor is no longer "alive".

spawnTime[n](Id, n) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, Cause, Pos).

spawnTime[n](Id, T) :- spawnTime[n-1](Id, T), alive[n-1](Id).

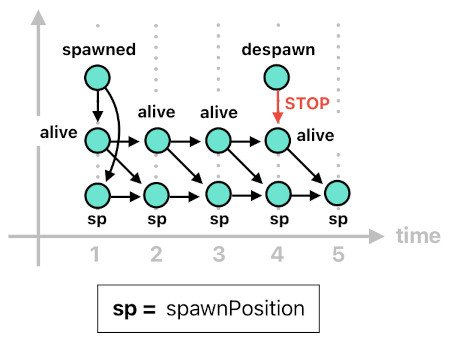

The actor's place of birth, too, can be defined in the same spirit. Just like "spawnTime", "spawnPosition" should be considered a chain of events which gets created when the actor is born, persists itself as long as the actor is still alive, and destroys itself as soon as the actor is found to be dead. The following code is the implementation.

spawnPosition[n](Id, Pos) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, Cause, Pos).

spawnPosition[n](Id, Pos) :- spawnPosition[n-1](Id, Pos), alive[n-1](Id).

But of course, the gameplay system needs to know the actor's current position besides its initial position. This is pretty straightforward to define; all it takes is to modify the previous rules of the "position" relation a bit, so as to ensure that the current position will no longer be defined once the actor disappears from the world. The code below demonstrates how it might be done.

position[n](X, Pos) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, Cause, Pos).

position[n](X, P) :- move[n-1](X, P), alive[n-1](X).

position[n](X, P) :- !move[n-1](X, _), alive[n-1](X), position[n-1](X, P).

As you can see, we now have the "alive" condition as part of the current position's recursive cases. Once "alive" no longer becomes available, "position" discontinues its chain of self-reproduction regardless of whether the actor wants to move or not.

Here is something I have not gone over yet. An actor, besides its own temporal and spatial state variables, needs to possess its own type. Otherwise, all actors will appear to be identical, and the game will be pretty boring. Actors must be able to carry distinct characteristics, such as their own colors, shapes, behavioral tendencies, functionalities, and so forth.

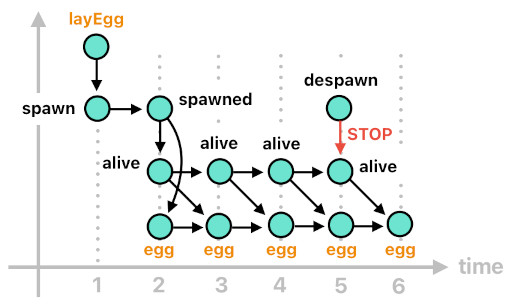

Such differentiation can be done by assigning a tag to each actor. An actor with the "egg" tag, for example, will let us treat it as an egg and use it for egg-related purposes. In this case, the word "egg" serves as the actor's type.

Here is a technical problem, though. When an actor spawns, how do we know that this actor is supposed to be an egg instead of something else, such as a pineapple, chocolate bar, or salmon?

We have a clue, fortunately. Do you remember that the "spawn" event is required to carry its own contextual argument called "Cause" in order to guarantee that the generated ID will be unique? The good news is that we can simply use this piece of information to decide which tag to attach to the spawned actor.

If the "Cause" argument of the "spawned" event is set to "layEgg", for instance, we will be able to tell that the actor was spawned because a chicken decided to lay an egg (i.e. The chicken raised the "layEgg" event, which in turn caused the "spawn" event to happen). Under such a circumstance, therefore, it should make sense to label the actor with the word "egg" in order to indicate that it is an egg, and preserve such a label as long as the actor is alive. The code below shows how it is done.

egg[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, layEgg, Pos).

egg[n](Id) :- egg[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).

If the "Cause" argument were set to something else such as "makeSandwich", the tag attached would have been different (e.g. "sandwich"). This is how we are able to spawn actors of specific types.

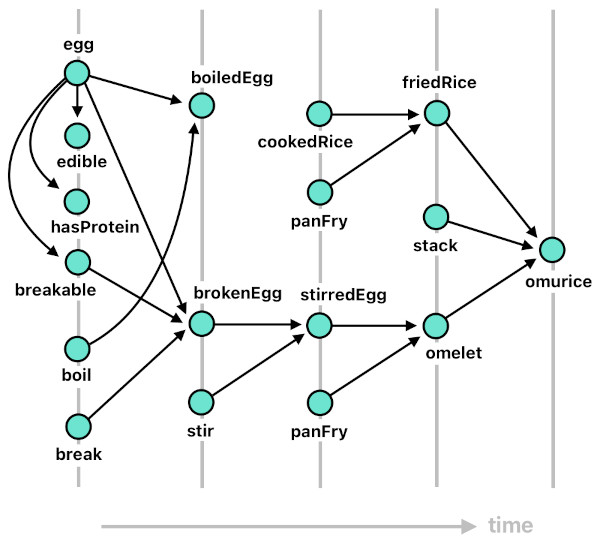

Once we manage to assign a tag (i.e. type) to an actor, the rest is history. As soon as the system recognizes the actor as an egg, for instance, it will automatically apply all the egg-related rules to this particular actor, such as the ones stated below.

edible(X) :- egg(X).

hasProtein(X) :- egg(X).

breakable(X) :- egg(X).

boiledEgg[n](X) :- egg[n-1](X), boil[n-1](X).

brokenEgg[n](X) :- egg[n-1](X), breakable[n-1](X), break[n-1](X).

stirredEgg[n](X) :- brokenEgg[n-1](X), stir[n-1](X).

omelet[n](X) :- stirredEgg[n-1](X), panFry[n-1](X).

omurice[n](Z) :- friedRice[n-1](X), omelet[n-1](Y), stack[n-1](X, Y, Z).The first three clauses are characteristics which can be derived from the fact that the actor is an egg. An egg is edible, has protein in it, and is breakable. These attributes do not need to be given to the actor individually, since they will all automatically be induced once the actor is tagged as "egg".

The succeeding clauses are a set of behavioral traits which are common to all eggs. If you boil an egg, for example, it will turn itself into a boiled egg. If you break an egg, it will become a broken egg. If you stir a broken egg, it will become a cupful of stirred egg. And if you pan-fry it, it will be transformed into an omelet. And of course, you can make omurice by stacking the omelet on top of fried rice.

(Note: These transformative rules are incomplete and have logical flaws in them. For example, once an egg becomes a broken egg, it should no longer be breakable (while still maintaining its status as an egg because breaking it does not make it a "non-egg"). Also, a broken egg should stay as a broken egg as long as no event interferes with its state. In the upcoming article, I will be dealing with this sort of problem.)

Such a "chain-reaction of thought" is theoretically boundless. Nothing really prevents it from being extended indefinitely, as long as a sufficient degree of freedom is provided. We began with the word "egg" alone, yet this was enough to give birth to its own vast tree of meaning, furnished with all sorts of ways in which an egg could be treated and/or manipulated. We call this kind of phenomenon a "butterfly effect".

Being able to spawn and despawn actors during runtime is such an indispensable feature for a gameplay system to have. It opens up a gateway to a plethora of opportunities in regard to the concept of life and death, as well as the cycle of nature in general (which encompasses the idea of reincarnation, karma, etc). It makes things far more dynamic than they would have been if they were statically declared as though they were parts of a stone sculpture.

The mechanic of spontaneous creation and destruction evinces its full potential in simulation games (e.g. ecosystem simulator, management simulator, social simulator, etc), in which actors oftentimes play the roles of either producers, consumers, or both.

Some actors are called "producers" because they produce brand new actors. Examples of them are plants, factories, power generators, as well as living things in general (because they reproduce).

Some actors are called "consumers" because they consume (destroy) existing actors. Examples of them are weapons, garbage disposers, decomposers, and animals (because they eat other lifeforms to survive).

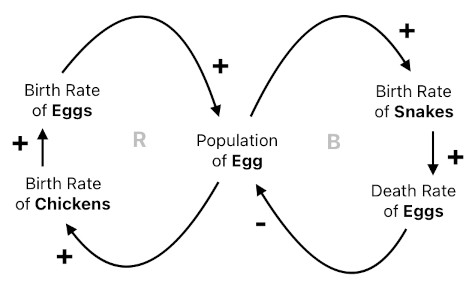

An example can be found in the case of a food chain. Imagine that there is a chicken and a snake at the same location, meaning that they are able to interact with each other at any moment. Let's say that the chicken lays an egg every time the clock ticks (The code below illustrates this mechanic).

layEgg[n](X) :- chicken[n](X).

spawn[n](X, layEgg, Pos) :- layEgg[n](X), position[n](X, Pos).Meanwhile, the snake devours any egg it happens to find in proximity. Whenever the snake eats an egg, the egg despawns (since it is "consumed" by the act of eating). The following code shows how it works.

eat[n](X, Y) :- snake[n-1](X), egg[n-1](Y), collide[n-1](X, Y).

despawn[n](Y) :- eat[n](X, Y).

At this point, you are probably aware of the grand cycle of production and consumption in this example. The chicken produces an egg, the snake consumes it, the chicken produces another egg, the snake consume it, and so on, thus exhibiting an oscillatory pattern. From an ecological point of view, this should (with a list of additional rules) eventually lead to fluctuations in the populations of chickens, their eggs, and snakes, as well as their long-term positive/negative feedback loops.

Analogous scenarios may be found in agriculture (i.e. seeding followed by harvesting), dairy (i.e. raising of cows followed by milking), and countless other phenomena.

(Will be continued in Part 9)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service