Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 5, 2024

This is Part 10 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

So far, I have been demonstrating how an actor's transformations (i.e. state transitions) could be represented in logic programming syntax. An example I came up with, as you may remember from the last article, was a set of alternative ways of handling an egg.

A perfectly normal egg, which has just been laid by a chicken, is able to be broken because it is being protected by a solid shell. Once you break it, it becomes a handful of liquid, thereby allowing you to either just pan-fry it directly (in which case it will be turned into a fried egg), or to first stir it an then pan-fry the result (in which case it will be turned into an omelet). This is a rudimentary example of an egg's tech tree.

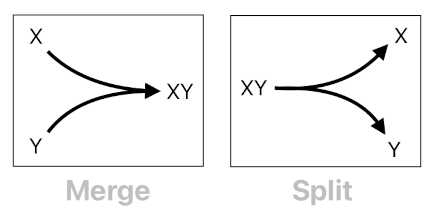

There is yet another aspect of transformations which I have not explained yet - the concept of merging and splitting. Sometimes, multiple objects combine into a single unit to form a compound structure (like atoms bonding with each other to form a molecule), or sometimes a compound structure gets broken down to multiple smaller units.

This means that transformation (i.e. state transition) is not all about a single line of progression in spacetime. In some cases, multiple lines (objects) merge into a single line, signifying an event where multiple things combine into one thing. In some other cases, a single line (object) splits into multiple lines, signifying an event where one thing decomposes itself into multiple things.

In fact, we have already seen an instance of combination before (in Part 8). Remember when I mentioned that you can make omurice by stacking an omelet on top of fried rice? This is clearly a scenario in which multiple objects come together to form a single compound. When they (i.e. omelet and fried rice) were hanging out individually, they were merely two separate entities, having nothing to do with each other. Once they get stacked up, however, they suddenly become parts of one shared object called "omurice". I will restate the formula below for a reminder.

omurice[n](Z) :- friedRice[n-1](X), omelet[n-1](Y), stack[n-1](X, Y, Z).There is something missing in this recipe, though. How shall we figure out the name (id) of this new actor called "Z"? Apparently, Z is supposed to indicate the omurice which has just been made by the act of stacking up an omelet on top of fried rice. But where does this come from?

This is the place where the definition of "multiple things combining into one thing" starts to get tricky. There are two ways of resolving this problem, so I will go over them one by one.

The first method is to simply assume that the omurice is represented not by a brand new actor, but by one of the existing actors. Before jumping directly into demonstration, I first ought to redefine the "stack" relation; its revised definition is shown in the following snippet, along with a new relation called "below":

below[n](X, Y) :- stack[n-1](X, Y).

below[n](X, Y) :- below[n-1](X, Y), alive[n-1](X), alive[n-1](Y), !unstack[n-1](X, Y).

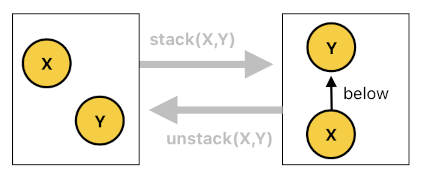

Here, the "stack" relation no longer takes 3 arguments (where the third one was meant to indicate the result of stacking two things). Instead, it now only takes 2 arguments, where the first one (X) represents what is below the other argument (Y). In other words, "stack[n](X, Y)" means, "Y has just been stacked on top of X at time n".

Once we finish stacking Y on top of X, X will of course be "below" Y (because if Y is above X, X must be below Y, right?). And this relation (i.e. "below") will continue to hold, up until the point at which the stack gets destroyed either by the process of "unstacking" or by the destruction of either one of its parts (X or Y).

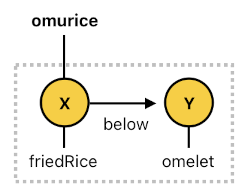

With this new definition, we are now able to come up with a more concrete depiction of what an omurice is. First of all, let me remind you that we can make an omurice by stacking an omelet on top of fried rice. This process can be carried out by raising the event "stack[n](X, Y)", where X is the fried rice and Y is the omelet.

The main issue is, which actor should the resulting omurice be? Spawning a brand new actor is definitely a valid option, yet it is also possible to avoid such a step altogether.

When we are putting an omelet on top of fried rice, we are not really creating a separate piece of matter out of nowhere; all we are doing is, we are simply "assembling" two existing pieces of matter together, without introducing anything new from a purely physical point of view (aka "Conservation of Mass"). Our habit of giving a distinct name (such as "omurice") to the result of such a process is just for the sake of efficiency in communication - an abstract means of referencing a collection of things, so as to avoid the necessity of repeating a verbose description (such as "omelet on fried rice") every time we refer to it.

So, representing an omurice as a separate actor is not really an absolute requirement, since such an actor will merely be used as a reference and hardly anything else. And the role of a reference can simply be played by an existing actor, such as the fried rice.

When I put an omelet on a plate of fried rice, an intuitively satisfying way to think about it is that I just "transformed" the plain old fried rice into something more advanced (aka "omurice"). I do not consider myself as a wizard who summoned something new out of nowhere.

After all, an ice cream with a cherry on top of it is still an ice cream, and a slice of cheese pizza with an anchovy on it is still a slice of cheese pizza. In both of these cases, the original identity of the subject has never been destroyed; it simply augmented itself to something slightly more complex (such as "cherry topped ice cream" or "anchovy pizza").

The same philosophy applies to the case of omurice. A plate of fried rice with an omelet added on top of it is still a plate of fried rice; it just happens to be carrying an additional constituent in it (i.e. omelet). Therefore, it is perfectly fine to say that this "augmented" fried rice should also be identified as an omurice. The following code demonstrates how this line of reason works.

omurice[n](X) :- friedRice[n-1](X), omelet[n-1](Y), stack[n-1](X, Y).

omurice[n](X) :- omurice[n-1](X), friedRice[n-1](X), below[n-1](X, Y), omelet[n-1](Y).

What is happening in the two rules above is quite straightforward. The first rule says that a plate of fried rice will also qualify as an omurice as soon as we put an omelet on top of it. The second rule says that such a resulting omurice will continue being an omurice as long as it is a plate of fried rice sitting below an omelet.

Here, the actor which represents the fried rice also simultaneously represents the omurice, thereby letting us keep track of a new conceptual entity without spawning any brand new actor. This is reminiscent of how a set is often being modeled in computer science, where one of the set's elements plays the role of its representative (Just like how the Eiffel Tower is often used to represent Paris).

But of course, this is just one of many examples of composition/decomposition. In some other examples, it might make more sense to come up with a brand new actor to represent the result of a combination. And if that happens to be the case, we better just spawn a new actor (i.e. generate a new unique ID) and use it as a reference.

To be able to manage such a type of reference, however, we will need to utilize yet another concept called "parent-child relation" (Game developers are probably already familiar with this). Once we know how to leverage its full power, we will be able to construct a hierarchy of objects - a neat way of organizing a compound structure. The root node of such a hierarchy (aka "tree"), then, will represent a complex object which is made up of simpler objects.

Greetings, fellow game developers! I know that you guys are familiar with the so-called "scene hierarchy" or "object hierarchy" in game programming. The vast majority of game engines (such as Unity) include this as one of their core built-in features, due to the fact that it solves a myriad of potential organizational problems. Just like a computer keeps track of files inside a hierarchy of directories (i.e. folders), a game engine keeps track of in-game elements (such as game-objects, prefabs, UI components, etc) inside the project's internal hierarchy.

Why keep things in the form of a hierarchy? The answer to this question is so obvious in most cases, that hardly anyone even feels the necessity of answering it.

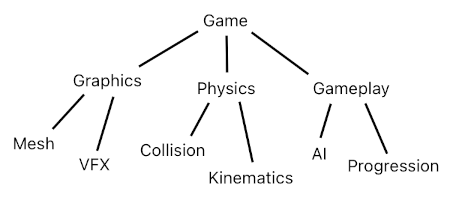

We know that a game, as a whole, is one gigantic system which is fairly complex. And because it is complex, we feel that we will be having an easier time developing it if we break it down into a group of somewhat simpler systems, such as "graphics", "physics", "UI", "gameplay", "networking", "config", and so on. Each one of these subsystems, however, is still too complex to handle, so we tend to realize that it will be even better if we break each of them into even simpler components.

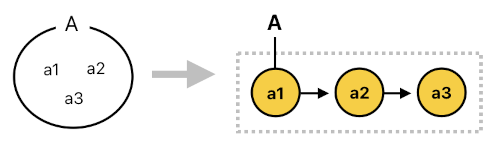

This kind of reasoning eventually leads to a hierarchical breakdown of systems (i.e. tree), where each parent node represents the ensemble of its child nodes.

The example I just described is a general overview of how a large-scale project might be managed, yet the same exact idea may as well be applied to pretty much any instance of composition. As we have seen before, multiple ingredients can be joined together to form a single compound. In this case, the ingredients are the "children" of their compound (i.e. parent).

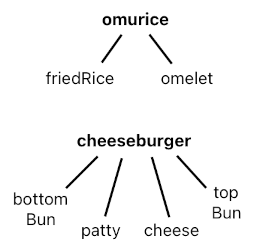

In the hierarchical worldview, an "omurice" is a parent with at least two children - fried rice and omelet. A "cheeseburger" is a parent who has at least four children - two buns (top and bottom), a patty, and a slice of cheese. Pretty much any object is the parent of its constituent parts.

The definition of the parent-child relation is shown below. First of all, the "addChild" event makes its first argument the parent of its second argument. This relation persists as long as we do not terminate it by raising the "removeChild" event.

parent[n](Parent, Child) :- addChild[n-1](Parent, Child).

parent[n](Parent, Child) :- parent[n-1](Parent, Child), !removeChild[n-1](Parent, Child).The "addChild" and "removeChild" events are the consequences of the underlying "setChild" event (the details are shown in the code below). The "removeChild" event automatically gets called whenever we set the parent of the child to something other than the child's previous parent, and the "addChild" event automatically gets called whenever we set the parent of the child to something other than "null" (Setting the parent to "null" is the same thing as simply detaching the child from its current parent).

removeChild[n](PrevParent, Child) :- setChild[n](NewParent, Child), parent[n](PrevParent, Child), notEqual(PrevParent, NewParent).

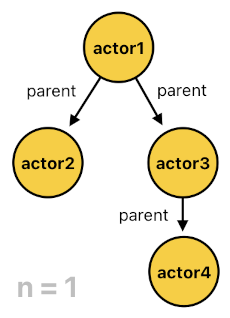

addChild[n](NewParent, Child) :- setChild[n](NewParent, Child), isNotNull(NewParent).In most cases, it is conventient to just use the "setChild" event to establish the parent-child relations among a group of actors. For example, the following code orders the game to construct a hierarchy which looks like the one displayed in the diagram below.

setChild[0](actor1, actor2).

setChild[0](actor1, actor3).

setChild[0](actor3, actor4).

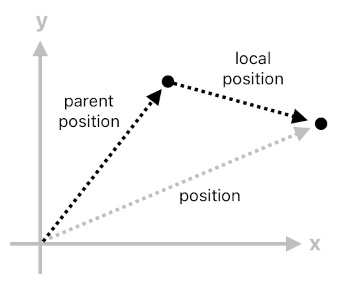

There is one thing I would like to point out, though, in regard to the positioning of child nodes. If you are a game developer, you are probably aware of the fact that there is some kind of "motion synchronization" going on in each parent-child relationship; that is, when a parent moves, its child usually follows its movement by the same exact distance and direction, whereas the converse is not usually true (unless they are part of a rigid body or something).

Such a mechanic can be implemented by first defining the (global) position of a child as the sum of its local position and its parent's global position (See the code below). The local position indicates the child's offset from the center of its parent. If an actor has no locatable parent (in which case only the negation of the "parentPosition" relation will be applicable), its global position will be identical to its local position.

parentPosition[n](Child, PP) :- parent[n](Parent, Child), position[n](Parent, PP).

position[n](X, P) :- parentPosition[n](X, PP), localPosition[n](X, LP), add(PP, LP, P).

position[n](X, LP) :- !parentPosition[n](X, PP), localPosition[n](X, LP).

And the way we initialize an actor's local position follows a similar logic. When an actor spawns (i.e. before it acquires any parent), its spawn-position becomes its local position. When it acquires a parent, its global offset from the parent becomes its local position. When it loses its current parent, its global position becomes its local position.

localPosition[n](X, P) :- spawnTime[n](X, n), spawnPosition[n](X, P).

localPosition[n](X, LP) :- addChild[n-1](Parent, X), alive[n-1](X),

position[n-1](X, P), position[n-1](Parent, PP), subtract(P, PP, LP).

localPosition[n](X, P) :- removeChild[n-1](_, X), alive[n-1](X),

position[n-1](X, P).And of course, this local position will persist through the passage in time up until the point of the actor's death, with occasional interceptions such as the "move" event (which forcibly overrides the current position).

localPosition[n](X), NewLP) :- !addChild[n-1](_, X), !removeChild[n-1](_, X),

move[n-1](X, NewP), alive[n-1](X),

localPosition[n-1](X, PrevLP), position[n-1](X, PrevP), subtract(NewP, PrevP, Offset),

add(PrevLP, Offset, NewLP).

localPosition[n](X, LP) :- !addChild[n-1](_, X), !removeChild[n-1](_, X),

!move[n-1](X, _), alive[n-1](X),

localPosition[n-1](X, LP).Here is another gameplay logic we should be aware of. When a parent gets destroyed, its children are usually expected to be destroyed as well (This is not an absolute requirement, but many game engines operate under such an assumption - including Unity). If we want this logic to be in action, we will need to write the following code as well.

despawn[n](Child) :- parent[n](Parent, Child), despawn[n](Parent).

removeChild[n](Parent, Child) :- parent[n](Parent, Child), !alive[n](Child).The things I have mentioned so far are all the essential stuff we need to know to be able to play with parent-child relations. In the next article, I will explain how these building blocks can be used to represent an omurice as a standalone actor, rather than a mere extraneous identity which is superficially being attached to one of its components (i.e. fried rice).

(Will be continued in Part 11)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service