Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 7, 2024

This is Part 11 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

As I have demonstrated recently, parent-child relations come in handy whenever we are dealing with hierarchical structures. In most cases, it is convenient to assume that a child is a component (i.e. part) of its parent, and a parent is a compound object which is made up of one or more of such components.

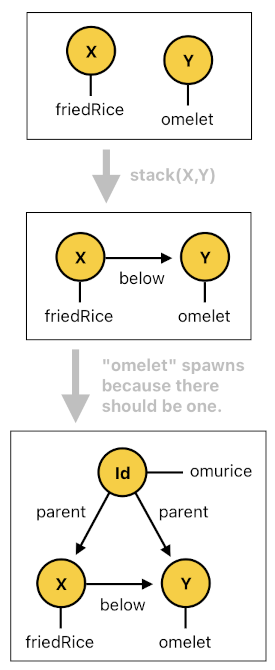

With this in mind, let us reimagine our omurice as a whole separate abstract entity which comprises two components (i.e. fried rice and omelet), rather than just an alternative interpretation of the fried rice we already have as an actor.

To do so, we ought to first make sure to spawn a new actor as soon as we stack the omelet on top of the fried rice, and then allow this new actor to represent the resulting omurice. The code below depicts the initial spawning portion of the logic.

spawn[n](<X, Y>, makeOmurice, null) :- friedRice[n](X), omelet[n](Y), stack[n](X, Y).One thing I should point out here is that the "Src" (Source) parameter of the "spawn" event is designed to be the tuple of two IDs - one which belongs to the fried rice, and the other one which belongs to the omelet. The reason why this is necessary is that, by the time the omurice (i.e. the actor which is supposed to represent the omurice) spawns, we would like it to remember what it is made out of. Otherwise, it won't be able to tell exactly which fried rice and omelet must be associated with itself.

Once the omurice spawns, we will indeed explicitly label it as "omurice" so as to let the rest of the world recognize it as an omurice without analyzing its anatomy. Such a label, then, shall persist as long as the actor lives (See the code below).

omurice[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeOmurice, Pos).

omurice[n](Id) :- omurice[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).This is not the end of the story, though. The omurice we just summoned into existence is supposed to represent the collective sum of its two components, which are called "fried rice" and "omelet", respectively. Therefore, we must establish a set of connections between the omurice and its components to explicitly state which ones are part of which.

Fortunately, we know how to do this. We know that the "spawned" event carries two IDs in its "Src" argument - the ID of the fried rice, and the ID of the omelet. So if we fetch the first item of "Src" (x), we will obtain the former, and if we fetch the second item of "Src" (y), we will obtain the latter.

The remaining task, then, is to make the omurice the parent of the given fried rice and omelet. The code implementation of this logic is displayed below.

setChild[n](Id, X) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeOmurice, Pos), x(Src, X).

setChild[n](Id, Y) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeOmurice, Pos), y(Src, Y).

There we have it. Since the omurice is now the parent of an actor named "fried rice" and another actor named "omelet", the system is able to tell that this particular actor (i.e. omurice) is a compound object which is made out of its two components called "fried rice" and "omelet".

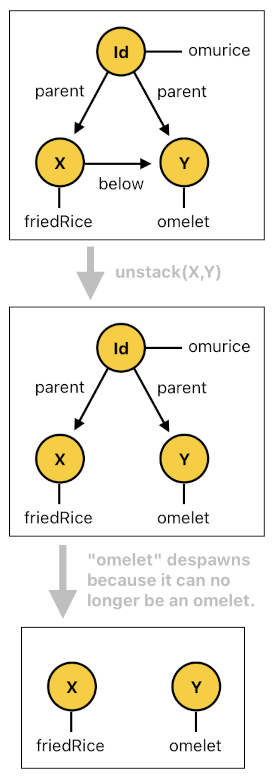

However, it is also important for us to ensure that this omurice will continue to exist as an omurice only as long as its internal structure qualifies itself as an omurice.

Let me give you a few examples. If I get rid of the omelet from the omurice, there will no longer be any "omurice" there because only the fried rice will be left. If I get rid of the fried rice from the omurice, there will no longer be any "omurice" there because only the omelet will be left. If I replace the existing omelet with another omelet, on the other hand, there will sill be an "omurice" there, although the question of whether this specific omurice is "the same thing" as the one which was there before is a bit tricky to answer (which reminds us of the Ship of Theseus).

Aside from philosophical ambiguities, however, we can pretty much agree on the point that an omurice will continue being an omurice only as long as it consists of fried rice and an omelet sitting on top of it. In other words, we need to detach the existing omurice from its current children and dispose it if we ever happen to find out that it is no longer identifiable as an omurice (See the code below).

canBeOmurice[n](Id) :-

parent[n](Id, X), friedRice[n](X),

parent[n](Id, Y), omelet[n](Y),

below[n](X, Y).

removeChild[n](Id, X) :- omurice[n-1](Id), !canBeOmurice[n](Id), parent[n](Id, X).

despawn[n](Id) :- omurice[n-1](Id), !canBeOmurice[n](Id).

And if we ever wish to manually dismiss an omurice by pulling its components apart, we may fancy that there is a special event called "disassemble" which, when invoked, detects the omurice's two core building blocks (i.e. fried rice and omelet) and unstacks them (Recall that the "unstack" event removes the stacking relation between the two given objects). Once unstacked, the fried rice will no longer be sitting "below" the omelet, which means that the omurice will no longer qualify as an omurice (i.e. The "canBeOmurice" predicate will be FALSE) and thus shall be despawned.

unstack[n](X, Y) :- omurice[n-1](Id), disassemble[n-1](Id),

parent[n-1](Id, X), friedRice[n-1](X),

parent[n-1](Id, Y), omelet[n-1](Y),

below[n-1](X, Y).At this point, you may have realized that there are two major categories of objects - those which are made of single actors (aka "elements"), and those which are made of multiple actors (aka "compounds"). The former are reminiscent of individual atoms which cannot be broken down further, whereas the latter are reminiscent of molecules which can be separated into their atomic constituents.

A compound is basically a hierarchy of actors, in which the root (i.e. topmost parent) represents the whole thing and its children represent its parts. Thus, we may imagine that each hierarchy is itself a compound object.

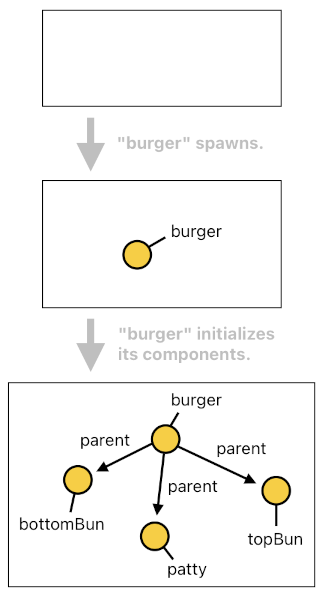

In the previous example, I demonstrated how we are able to construct a compound by assembling a multitude of existing actors together (by means of the stacking operation, etc). However, it is also also possible to let the system automatically initialize the compound's internal structure by the time its root spawns.

Let's say, for instance, that there is an event called "makeBurger" which spawns a burger at the position of the source actor (i.e. X). When this event gets raised, an actor which represents a burger gets created.

Suppose, however, that a burger is defined as a parent of its three core ingredients - the bottom bun, the patty, and the top bun. If any of these three turns out to be missing, the parent will no longer be identifiable as a burger.

The following code illustrates how the "makeBurger" event triggers the spawning of a burger, as well as how it immediately kicks off its own chain reaction immediately upon its birth in order to initialize its own hierarchical structure. As you will see below, the spawning of the burger automatically causes 3 additional spawning processes - (1) Spawning of the bottom bun, (2) Spawning of the patty, and (3) Spawning of the top bun.

spawn[n](X, makeBurger, Pos) :- makeBurger[n](X), position[n](X, Pos).

spawned[n]("{n}_{Src}_{Cause}", Src, Cause, Pos) :- spawn[n-1](Src, Cause, Pos).

spawn[n](Id, makeBurger_bottomBun, Pos) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger, Pos).

spawn[n](Id, makeBurger_patty, Pos) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger, Pos).

spawn[n](Id, makeBurger_topBun, Pos) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger, Pos).Once spawned, these three component actors will instantly receive their appropriate labels (i.e. "bottomBun", "patty", and "topBun") and become the children of the burger. All these three processes will be executed in parallel because they all belong to separate causes (i.e. "makeBurger_bottomBun", "makeBurger_patty", and "makeBurger_topBun").

bottomBun[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger_bottomBun, Pos).

bottomBun[n](Id) :- bottomBun[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).

setChild[n](Src, Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger_bottomBun, Pos).

patty[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger_patty, Pos).

patty[n](Id) :- patty[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).

setChild[n](Src, Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger_patty, Pos).

topBun[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger_topBun, Pos).

topBun[n](Id) :- topBun[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).

setChild[n](Src, Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger_topBun, Pos).

This completes the automatic initialization of the burger's internal hierarchy. All we had to do was spawn a burger; the rest of the processes were simply being handled by the predefined rules above.

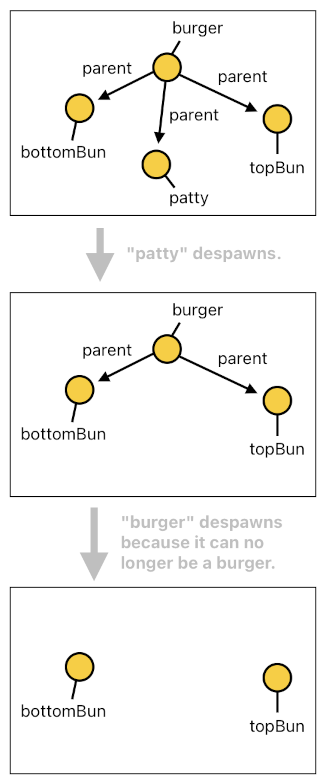

There is one more thing we ought to do, though - the maintenance and disposal of the burger's identity. Just like an omurice is allowed to stay being an omurice only as long as it is made out of a stack of fried rice and omelet, a burger, too, must satisfy its own list of criteria in order to ensure its continued existence.

A burger is a compound which is made up of three children - the bottom bun, the patty, and the top bun. There might be additional children, but the presence of such extraneous ingredients do not really matter when it comes to the burger's identity as a generic "burger" (Because, you know, a "double-cheese bacon burger" is still a "burger"; it just happens to be a richer variant). If any of these three children turns out to be missing, the parent will no longer be considered a burger and thus will have to be exterminated.

The code listed here is the set of rules which tell us how such a criterion will be enforced.

burger[n](Id) :- spawned[n-1](Id, Src, makeBurger, Pos).

burger[n](Id) :- burger[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).

canBeBurger[n](Id) :-

parent[n](Id, C1), bottomBun[n](C1),

parent[n](Id, C2), patty[n](C2),

parent[n](Id, C3), topBun[n](C3).

removeChild[n](Id, X) :- burger[n-1](Id), !canBeBurger[n](Id), parent[n](Id, X).

despawn[n](Id) :- burger[n-1](Id), !canBeBurger[n](Id).

The first two rules simply state that an actor which has just been spawned by the "makeBurger" event will initially be considered a "burger", and will continue being so as long as it stays alive. This part is structurally identical to that of the omurice example we saw before.

The last two rules, too, structurally resemble those of the omurice example. They are there to ensure that a burger will be safely disposed when it no longer qualifies as a burger.

The rule in the middle is the most important part. The "canBeBurger" predicate basically tells us whether the given burger can still be considered a "burger" during the current time step (i.e. 'n') - that is, whether it still consists of a bottom bun, a patty, and a top bun. If so, this burger will maintain its status as a burger. If not, it will be wiped out of existence.

The ability to define a piece of data as a hierarchy (i.e. tree), either before or after instantiating its components, is an invaluable feature to have in complex and emergent systems.

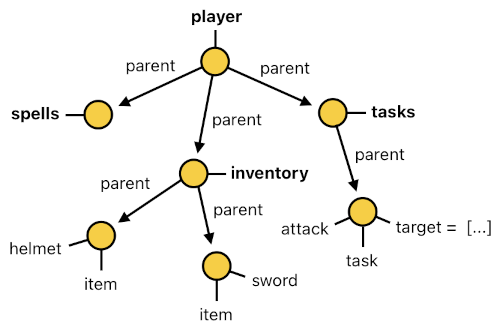

Oftentimes, game developers feel the necessity to design in-game agents (aka "characters") which are equipped with their own stats, inventories, status effects, scheduled tasks, relationships with other agents, and other pieces of dependent data. In such cases, it is usually sensible to devise each agent as a root node (i.e. topmost parent) of its own subtree, within which all of its inner data entries are stored. The figure below is an illustration of it.

The main benefit of this conceptual model is that it is extremely scalable. Do you want to implement new gameplay features? No problem! Just add more children the actor to support such additional features. If you wish that every NPC had its own inventory of items, for instance, all you need to do is add a chunk of code which creates an "inventory actor" and attaches it to every freshly spawned NPC actor, like the one shown here:

spawn[n](Id, makeInventory, Pos) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeNPC, Pos).

inventory[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeInventory, Pos).

inventory[n](Id) :- inventory[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).

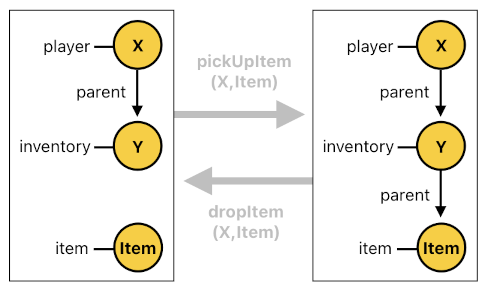

setChild[n](Src, Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeInventory, Pos).Once an NPC gets equipped with its own inventory, we are able to let this NPC either pick up an item (by means of the "pickupItem" event) or drop an item (by means of the "dropItem" event).

setChild[n](Y, Item) :- pickupItem[n-1](X, Item), parent[n](X, Y), inventory[n](Y).

removeChild[n](Y, Item) :- dropItem[n-1](X, Item), parent[n](X, Y), inventory[n](Y).

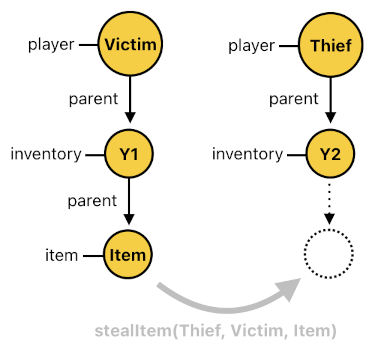

We may as well choose to design a rather interesting game mechanic, such as letting an actor steal an item from another actor. Such a feature could be implemented by using the following rule:

setChild[n](Y2, Item) :- stealItem[n-1](Thief, Victim, Item),

parent[n](Victim, Y1), inventory[n](Y1), parent[n](Y1, Item),

parent[n](Thief, Y2), inventory[n](Y2).

A special exception to such a general rule, too, can be contrived by writing a few additional lines of code. Suppose that we want an NPC to be able to prevent its items from being stolen as long as it possesses an item called "stealShield". A steal-shield is an item which protects all other items in the inventory from thieves. The following code implements this steal-protection ability.

hasStealShield[n](X) :-

parent[n](X, Y), inventory[n](Y),

parent[n](Y, Item), stealShield[n](Item).

setChild[n](Y2, Item) :- stealItem[n-1](Thief, Victim, Item),

!hasStealShield[n-1](Victim),

parent[n](Victim, Y1), inventory[n](Y1), parent[n](Y1, Item),

parent[n](Thief, Y2), inventory[n](Y2).(Will be continued in Part 12)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service