Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 8, 2024

This is Part 12 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

Let me go back to the omurice example and further elaborate upon its hidden intricacies. You may have noticed already, but there is one missing feature in the system I have been devising so far. It is the apparent lack of the system's ability to automatically recognize a specific pattern in the environment and conjure up an appropriately labeled actor for it.

For instance, the code I showcased in the previous article only describes how to explicitly construct an omurice by selecting a pair of specific ingredients (i.e. fried rice and omelet) and making a stack out of them. The rule which executes this logic is reproduced below.

spawn[n](<X, Y>, makeOmurice, null) :- friedRice[n](X), omelet[n](Y), stack[n](X, Y).This rule, however, misses occasions during which the stacking of fried rice and omelet may occur "by accident" - that is, not by explicitly raising the event called "stack", but by unintentionally putting an omelet on a plate upon which fried rice happens to be situated. In such cases, it will be necessary to detect the presence of such a stack and instantiate an omurice off of them.

Such a line of reasoning can be handled by the additional rule shown below. Instead of listening to the stacking event, it observes the world, checks to see if there is any fried rice which happens to be below an omelet, and spawns an omurice if it is the case.

(Note: "mod(n, 3, 0)" ensures that the checking of the status only happens once during each 3-step time interval. Its purpose is to prevent the spawning of multiple copies of omurice.)

spawn[n](<X, Y>, makeOmurice, null) :-

mod(n, 3, 0),

friedRice[n](X), below[n](X, Y), omelet[n](Y),

!childrenOfOmurice[n](X, Y).

childrenOfOmurice[n](X, Y) :-

parent[n](P, X), parent[n](P, Y), omurice[n](P).One might say, "Hey! This is unnecessary. There is no way to stack one thing upon another without calling the "stack" event anyways. So why even bother creating such a superfluous rule? If there ever happens to be a stack of fried rice and omelet, the original rule which listens to the "stack" event will handle such an occasion without missing anything."

This makes sense within the context of what has been demonstrated so far, yet let us not be so rash as to overlook some of the hidden pitfalls.

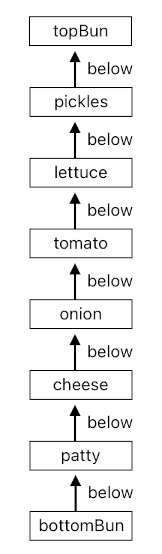

First of all, we better contemplate upon the meaning of the word "below". What does it mean to be "below" something? Take the anatomy of a burger for example. A typical American cheeseburger comprises a stack of many ingredients, such as buns, patty, cheese, onion, etc.

If we imagine a guy who is making such a burger (e.g. Spongebob), we will be able to picture him putting a bun on the table, a patty upon the bun, a sliced cheese upon the patty, a sliced onion upon the cheese, a sliced tomato upon the onion, a lettuce upon the tomato, pickles upon the lettuce, and finally another bun upon the pickles. This process may as well be expressed by the following lines of code (I am assuming here that the guy was producing the burger during the time interval of 0 to 6).

stack[0](bottomBun, patty).

stack[1](patty, cheese).

stack[2](cheese, onion).

stack[3](onion, tomato).

stack[4](tomato, lettuce).

stack[5](lettuce, pickles).

stack[6](pickles, topBun).

This is basically a chain of "stack" relations, leading from the lowermost to the upppermost ingredient. Such a chain obviously forms one large stack, which, as a whole, is commonly referred to as a "cheeseburger".

Here, let me ask you a question. Is the patty sitting below the cheese? Oh yes, indeed! The "stack" event which occurred at time 1 clearly says that the guy stacked the cheese on top of the patty, which meaning that the patty must be below the cheese.

Let me ask you another question. Is the patty sitting below the onion? Yes, of course. Since the patty is below the cheese and the cheese is below the onion, we must be able to infer that the patty is below the onion. Just because the patty is not directly touching the onion does not mean that the patty is not below the onion.

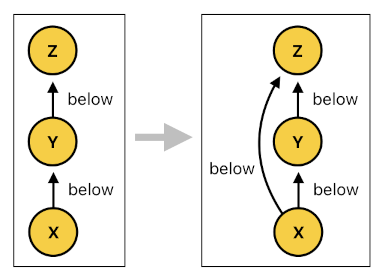

By the same spirit, we should also be able to assure that the lettuce is below the top bun, the onion is below the pickles, the bottom bun is below the top bun, and so on. This implies that the relation called "below" is transitive in nature - that is, if X is below Y and Y is below Z, then X must be below Z. And in order to reflect this property, we are obliged to include the following rule in the codebase:

below[n](X, Z) :- below[n](X, Y), below[n](Y, Z).

It is not difficult to demonstrate how this works in our cheeseburger example. Once the burger-making guy finishes stacking up all the ingredients (from bottom to top), the Prolog environment will be left with the following predicates (See the code below) which are the results of the series of "stack" events shown previously. Here, we are looking at time 7, the moment after the end of the stacking process.

below[7](bottomBun, patty)

below[7](patty, cheese)

below[7](cheese, onion)

below[7](onion, tomato)

below[7](tomato, lettuce)

below[7](lettuce, pickles)

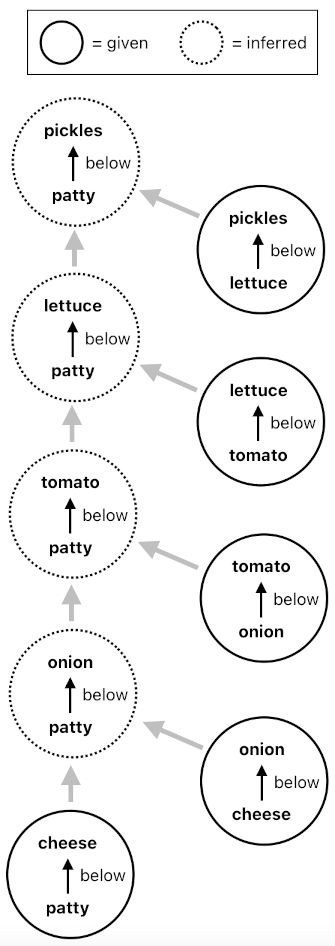

below[7](pickles, topBun)So far, nothing explicitly mentions that the patty is below the onion, the lettuce is below the top bun, or that the onion is below the pickles. Using the transitive property of "below", however, we are able to derive the "below" relationships of the items which are not necessarily adjacent to one another. For example, the system is able to conclude that the patty is below the pickles by successively generating a chain of inferences, like the ones shown here:

below[7](patty, pickles)

---> below[7](patty, Y), below[7](Y, pickles)

---> below[7](patty, Y = lettuce?) below[7](lettuce, pickles)

below[7](patty, lettuce)

---> below[7](patty, Y), below[7](Y, lettuce)

---> below[7](patty, Y = tomato?), below[7](tomato, lettuce)

below[7](patty, tomato)

---> below[7](patty, Y), below[7](Y, tomato)

---> below[7](patty, Y = onion?), below[7](onion, tomato)

below[7](patty, onion)

---> below[7](patty, cheese), below[7](cheese, onion)

The ability to discover such indirect instances of the "below" relation comes in handy when we want the system to automatically detect certain types of abstract objects and give them unique identities.

For example, let us say that a sandwich refers to any stack which consists of two buns and anything in between (i.e. It will be called a "ham sandwich" if there is a ham between the buns, an "egg sandwich" if there is an egg between the buns, a "bun sandwich" if there is yet another bun between the two outermost buns, or even an "empty sandwich" if there is nothing in between). We can let the system spontaneously find out such a type of stack and generate a "sandwich actor" off of it, by means of the rules shown below:

spawn[n](<X, Y>, makeSandwich, null) :-

mod(n, 3, 0),

bottomBun[n](X), below[n](X, Y), topBun[n](Y),

!childrenOfSandwich[n](X, Y).

childrenOfSandwich[n](X, Y) :-

parent[n](P, X), parent[n](P, Y), sandwich[n](P).

sandwich[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeSandwich, Pos).

sandwich[n](Id) :- sandwich[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).

setChild[n](Id, X) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeSandwich, Pos), x(Src, X).

setChild[n](Id, Y) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeSandwich, Pos), y(Src, Y).

...A stack which qualifies itself as a sandwich does not need to be bound to just one identity called "sandwich". We might as well let the environment detect a multitude of (potentially overlapping) identities and turn them into their own abstract objects, such as "burger", "cheese sandwich", etc.

A stack which comprises two buns and a patty between them can be referred to as a "burger". So, let us spawn a "burger actor" off of these three core components whenever that happens to be the case.

spawn[n](<X, Y, Z>, makeBurger, null) :-

mod(n, 3, 0),

bottomBun[n](X), below[n](X, Y),

patty[n](Y), below[n](Y, Z),

topBun[n](Z),

!childrenOfBurger[n](X, Y, Z).

childrenOfBurger[n](X, Y, Z) :-

parent[n](P, X), parent[n](P, Y), parent[n](P, Z), burger[n](P).

burger[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger, Pos).

burger[n](Id) :- burger[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).

setChild[n](Id, X) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger, Pos), x(Src, X).

setChild[n](Id, Y) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger, Pos), y(Src, Y).

setChild[n](Id, Z) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeBurger, Pos), z(Src, Z).

...Besides, a stack which comprises two buns and a slice of cheese between them can be referred to as a "cheese sandwich" because it is a sandwich with cheese in it (It may as well be called "grilled cheese sandwich" if the cheese were grilled).

spawn[n](<X, Y, Z>, makeCheeseSandwich, null) :-

mod(n, 3, 0),

bottomBun[n](X), below[n](X, Y),

cheese[n](Y), below[n](Y, Z),

topBun[n](Z),

!childrenOfCheeseSandwich[n](X, Y, Z).

childrenOfCheeseSandwich[n](X, Y, Z) :-

parent[n](P, X), parent[n](P, Y), parent[n](P, Z), cheeseSandwich[n](P).

cheeseSandwich[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeCheeseSandwich, Pos).

cheeseSandwich[n](Id) :- cheeseSandwich[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).

setChild[n](Id, X) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeCheeseSandwich, Pos), x(Src, X).

setChild[n](Id, Y) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeCheeseSandwich, Pos), y(Src, Y).

setChild[n](Id, Z) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeCheeseSandwich, Pos), z(Src, Z).

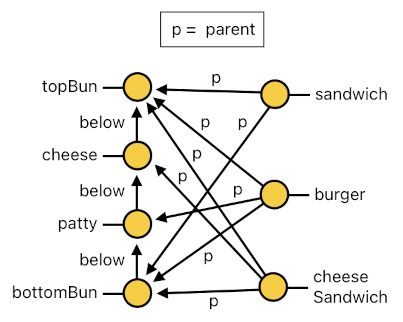

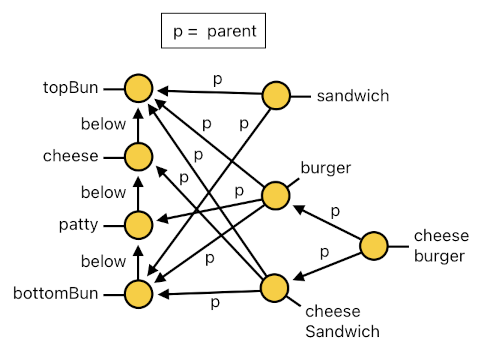

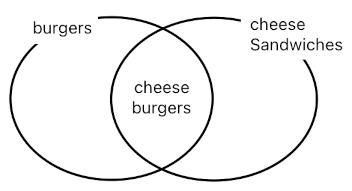

...This means that, if we put a bun on the table, a patty on top of the bun, a cheese on top of the patty, and finally another bun on top of the cheese, this particular stack will be endowed with 3 concurrent identities - (1) "Sandwich" because it contains two buns as well as something additional in between, (2) "Burger" because it has two buns and a patty in between, and (3) "Cheese Sandwich" because it has two buns and a slice of cheese in between.

But wait! There is more. Whenever we happen to discover a stack of ingredients which is simultaneously identifiable as both a burger and a cheese sandwich, we must be able to claim that such a stack is also identifiable as a cheeseburger. And if we ever wish to make sure that every cheeseburger be represented by its own separate entity (i.e. actor), we will need to write down the following code:

spawn[n](<X, Y>, makeCheeseburger, null) :-

mod(n, 3, 0),

burger[n](X), parent[n](X, B1), bottomBun[n](B1), parent[n](X, B2), topBun[n](B2),

cheeseSandwich[n](Y), parent[n](Y, B1), parent[n](Y, B2),

!childrenOfCheeseburger[n](X, Y).

childrenOfCheeseburger[n](X, Y) :-

parent[n](P, X), parent[n](P, Y), cheeseburger[n](P).

cheeseburger[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeCheeseburger, Pos).

cheeseburger[n](Id) :- cheeseburger[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).

setChild[n](Id, X) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeCheeseburger, Pos), x(Src, X).

setChild[n](Id, Y) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, makeCheeseburger, Pos), y(Src, Y).

canBeCheeseburger[n](Id) :-

parent[n](Id, X), burger[n](Id, X),

parent[n](Id, Y), cheeseSandwich[n](Id, Y).

removeChild[n](Id, X) :- cheeseburger[n-1](Id), !canBeCheeseburger[n](Id), parent[n](Id, X).

despawn[n](Id) :- cheeseburger[n-1](Id), !canBeCheeseburger[n](Id).

Here, the first rule says that if there is both a burger and a cheese sandwich which share the same exact pair of buns, their corresponding stack must be identified as a cheeseburger. A cheeseburger is an abstract object which justifies its own existence based upon the existence of two slightly less abstract objects (i.e. a burger and a cheese sandwich). As soon as at least one of these components dies out, the cheeseburger will cease to exist (Why? Because a burger which is not a cheese sandwich is not a cheeseburger, and a cheese sandwich which is not a burger is not a cheeseburger).

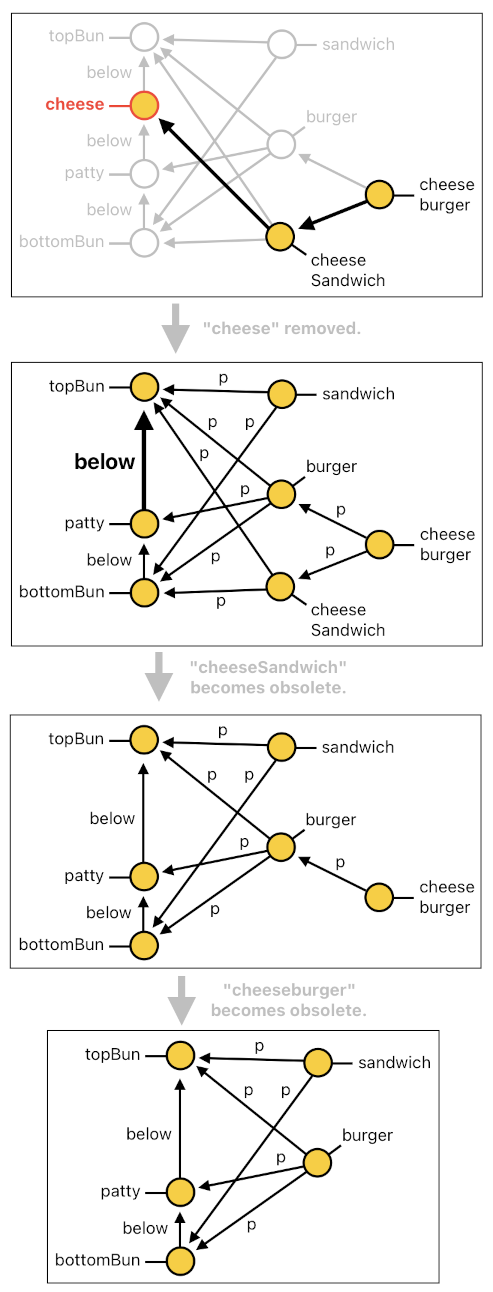

The benefit of having multiple layers of abstraction is that it allows us to selectively manipulate the game world in all sorts of clever ways. Imagine, for example, that there is a monster which only eats cheese from cheeseburgers (It refuses to eat anything else for some reason). Whenever this monster eats, therefore, we must make sure to remove the cheese from whichever cheeseburger from which it happens to be stealing cheese.

Such a tricky mechanic can be implemented via the code shown below. As soon as the monster steals cheese from a cheeseburger (which corresponds to X) by invoking the event called "removeCheeseFromCheeseburger", the system searches for the given cheeseburger's cheese component by traversing its tree of abstraction and spotting the node which is labeled as "cheese", and proceeds to remove it.

getCheeseFromCheeseburger[n](X, Cheese) :-

cheeseburger[n](X),

parent[n](X, CS), cheeseSandwich[n](CS),

parent[n](CS, B1), bottomBun[n](B1),

below[n](B1, Cheese), cheese[n](Cheese).

despawn[n](Cheese) :-

removeCheeseFromCheeseburger[n-1](X),

getCheeseFromCheeseburger[n](X, Cheese).This piece of logic, however, takes a bit of care to prevent undesirable side effects. When we are removing an element from the middle of a stack, for instance, we do not necessarily want the original stack to be permanently broken into two parts - the one below the removed element, and the one above the removed element. So, if we do not wish a cheeseburger to be split into two parts whenever a monster steals cheese from it, we better include yet another rule which ensures that the destruction of a node within a linked list of "below" relations will always be accompanied by the gluing of its neighbors (See the following code).

stack[n](X, Z) :- despawn[n](X), below[n](Y, X), below[n](X, Z).

The things which have been demonstrated so far may look a bit too complicated, though. And indeed, it is a reasonable impression to have, especially when we consider the sheer amount of code we are compelled to write just to support the automatic creation and destruction of abstract entities.

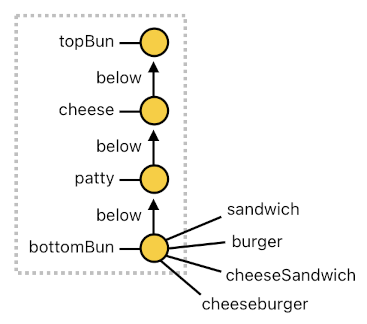

If representing compound objects as their own separate actors (such as "burger actor", "cheeseburger actor", etc) is not an absolute requirement, therefore, it may be a better idea to just allow the bottommost elements of their corresponding ingredient-stacks to serve as their representatives (similar to what we did in the first omurice example).

The code below is the aforementioned rules of automatic identity detection, redesigned in a much more concise manner. Here, we are no longer spawning brand new actors to indicate the presence of abstract objects such as "sandwich", "burger", or "cheeseburger". Instead, we are simply attaching extra identities to the bottommost ingredient (i.e. bottom bun) and letting it reflect the characteristics of the whole stack.

sandwich[n](X) :- bottomBun[n](X), below[n](X, Y), topBun[n](Y).

burger[n](X) :- sandwich[n](X), below[n](X, Y), patty[n](Y), below[n](Y, Z), topBun[n](Z).

cheeseSandwich[n](X) :- sandwich[n](X), below[n](X, Y), cheese[n](Y), below[n](Y, Z), topBun[n](Z).

cheeseburger[n](X) :- burger[n](X), cheeseSandwich[n](X).

The mechanic of stealing cheese from a cheeseburger, too, can be simplified tremendously under this new condition. Since we are no longer representing a cheeseburger as a tree of abstract nodes, all we have to do here is simply begin examining the burger's stack from the bottom (i.e. bottom bun), find the cheese, and remove it.

despawn[n](Cheese) :-

removeCheeseFromCheeseburger[n-1](X),

cheeseburger[n](X), below[n](X, Cheese), cheese[n](Cheese).(Will be continued in Part 13)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service