Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 12, 2024

This is Part 13 of the series, "Game Programming in Prolog". In order to understand what is going on in this article, please read Part 1 first.

In the previous few articles, I primarily spent time illustrating how abstract (compound) objects could be represented in terms of logical relations. This time, I will change the subject a bit and start talking about some of the advanced sorts of interactions which may occur among gameplay agents.

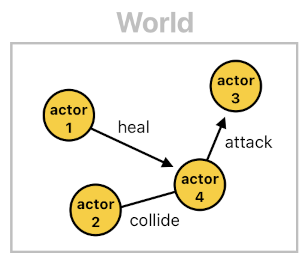

Let me recapitulate the overall structure of the game world. First of all, we have this thing called "the world" which encompasses the entirety of what is happening in our Prolog environment. It is made up of facts (i.e. instances of logical relations), each of which may belong to a certain point in time. A fact which possesses such a time parameter can be referred to as an "event", since it is representative of what happened at the given moment in time.

Symbols which make up the arguments of each fact, on the other hand, usually represent actors. An actor is an in-game object which may contain its own set of states as well as behaviors (Think of an actor as a state machine). In general, game mechanics can be defined in terms of ways in which certain types of actors interact with one another.

Actors interact in many ways. Sometimes they do when they touch each other (i.e. collide), or sometimes they do when they see each other from a distance. In some occasions, interactions appear in passive forms (e.g. An egg boiling because there is fire nearby, etc). Sometimes, they may even introduce effects which persist after their initial sources disappear.

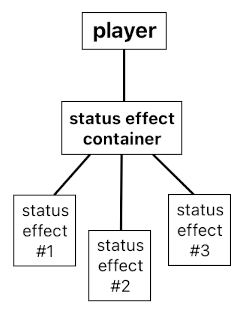

An effect which "sticks" to its target and lasts longer than the event from which it originated, is often called a "status effect" (aka "status condition"). And we often find that it is quite convenient to keep track of such a parasitic entity as a child node of a tree, where the root is the actor (e.g. player) to which the effect is being applied.

By modeling an actor as a hierarchical data structure (i.e. tree) instead of just a singleton with a bunch of keywords attached to it, we are able to manage a wide range of complex game mechanics without confusing ourselves too much. In this article, I will be demonstrating some of the hidden intricacies (as well as pitfalls) of such a hierarchy-oriented game design by outlining one of its most illustrative examples. It is what I would refer to as the "spell system".

The word "spell" is nothing more than an alternative terminology for "status effect"; I just chose this particular word because it happened to be more concise.

A spell is basically an effect which, when applied to an actor, occupies its body and lives in it for some duration. While a spell is alive, it keeps influencing its host's state in some way or another. Here are some of its typical examples:

(1) A damage-spell decrements the actor's health each time the clock ticks.

(2) A heal-spell increments the actor's health each time the clock ticks.

(3) A stun-spell blocks the actor's movement.

(4) A booster-spell amplifies the actor's movement speed.

... and so on.

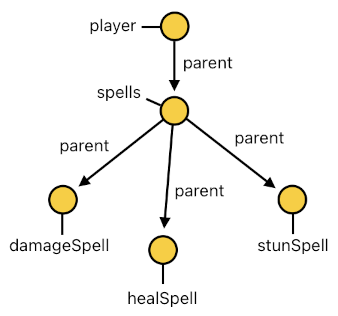

Let me begin explaining how spells could be implemented in our Prolog-based gameplay system. Since an actor may contain a fairly huge number of ongoing spells, it will be sensible for us to assume that each spell is a child node of one of the actor's intermediary nodes called "spells". Just like "inventory" is the container of items, "spells" can be thought of as the container of spells.

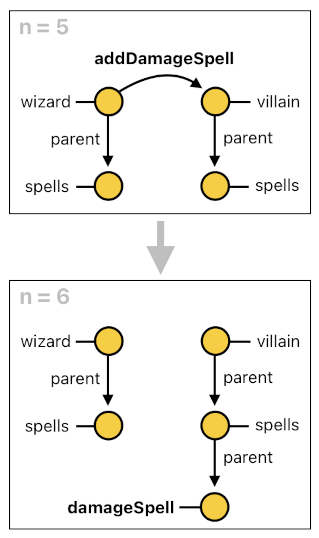

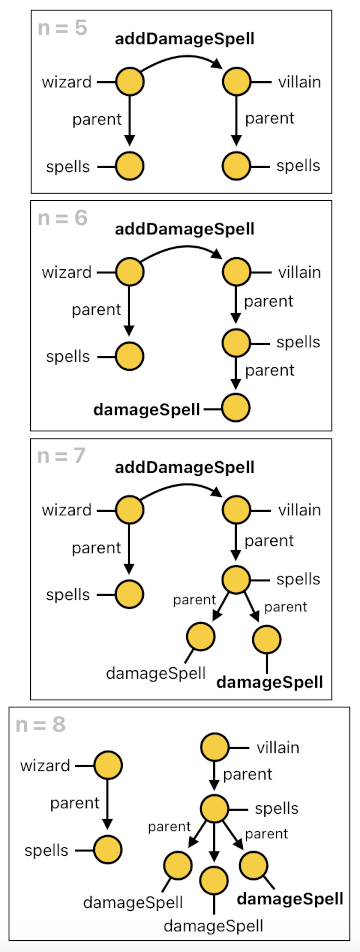

Imagine that there is an event called "addDamageSpell" which adds a new damage-spell to the target actor. Let's say that there are two actors, called "wizard" and "villain", and that the wizard decided to cast a damage-spell to the villain by calling this event. The following rule will then instantiate a damage-spell.

spawn[n](<Caster, Target>, addDamageSpell, null) :- addDamageSpell[n](Caster, Target).

If we suppose that the wizard cast the damage-spell at time 5, the spell's spawning process will be carried out by the three steps shown below. Notice that the casting of the spell at time 5 (i.e. "addDamageSpell[5](...)") instantly raised the "spawn" event which, after the delay of a single time step, completed the birth of the spell by generating a new unique ID (i.e. "6_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell").

(STEP 1):

addDamageSpell[5](wizard, villain)

(STEP 2):

spawn[5](<wizard, villain>, addDamageSpell, null)

(STEP 3):

spawned[6](6_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell, null)Once spawned, this damage-spell will keep existing as long as it is alive (i.e. does not despawn). Aside from ensuring its persistence through the passage in time, however, it also puts itself inside the target's body by making itself a child of the target's "spells" node. The code below ensures that these rules will apply to every damage-spell.

damageSpell[n](Id) :- spawned[n](Id, Src, addDamageSpell, Pos).

damageSpell[n](Id) :- damageSpell[n-1](Id), alive[n-1](Id).

setChild[n](S, Id) :-

spawned[n](Id, Src, addDamageSpell, Pos),

y(Src, Target), parent[n](Target, S), spells[n](S).

How about removing the spell? You know, when we add a new spell, we better plan to get rid of it later on as well, for otherwise there will soon be truckloads of spells piling up over time.

First of all, a couple of the parent-child rules I had introduced in Part 10 will ensure that a spell will die out as soon as its parent dies out (i.e. When a parent despawns, all of its children are expected to despawn too). This means that, when the villain gets killed, its "spells" node (i.e. spell container) will despawn, which in turn will make all of its ongoing spells despawn automatically.

However, we do not want all spells to simply stick to their host up until the moment of its death. Therefore, we ought to include additional rules to allow other means of removing a spell (See the code below). The first rule simply enables us to delete a damage-spell by invoking an event called "removeSpell", and the other two rules ensure that each damage-spell will "expire" (become obsolete and die out) exactly 10 time steps after its birth.

despawn[n](Id) :- damageSpell[n](Id), removeSpell[n](Id).

lifespan[n](Id, 10) :- damageSpell[n](Id).

despawn[n](Id) :- spawnTime[n](Id, T), lifespan[n](Id, Span), add(T, Span, EndTime), equal(n, EndTime).Now, let us suppose that the villain contains one active damage-spell in it. The job of a damage-spell, as you might have guessed, is to damage its host on a regular basis (i.e. during each time step). The rule listed below is what impels each damage-spell to apply a damage of magnitude "1" to its current host.

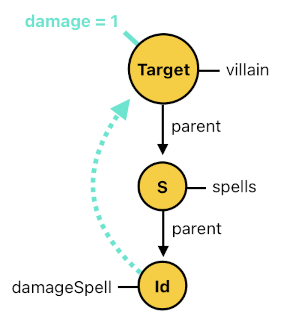

damage[n](Target, 1) :- damageSpell[n](Id), parent[n](S, Id), parent[n](Target, S).

Changing the villain's health based upon the currently imposed damage is pretty straightforward. Imagine that the villain has a numerical attribute called "health", which is expressible as a relation such as "health[n](X, H)" where X is the ID of the villain and H is its health at time 'n'.

It will then make sense to update the current health of the villain by subtracting it by the amount of damage applied. When the resulting health is less than or equal to zero, the villain will die. The following code is the implementation of these mechanics.

health[n](X, H2) :- health[n-1](X, H), damage[n](X, D), subtract(H, D, H2).

despawn[n](X) :- health[n](X, H), lessThan(H, 1).There is something fishy, though. The rule which updates the current health of the actor says that the new health is the result of subtracting the previous health by the incoming damage. But, what does this "incoming damage" mean, really? Is it just a single event, occurring just once at each moment in time? What if there are multiple sources of damage, then?

This is where the trouble begins. The wizard's damage-spell, which was cast at time 5, is not necessarily the only source of damage which the villain is going to receive. There might be other ongoing damage-spells inside the villain's body, or there might be other adversaries who have been actively attacking the villain. The idea is that there could be multiple causes of damage; if they are targeted against the same actor (i.e. villain), they ought to all add up.

The code below is a brute-force solution to handle this situation. Suppose that there are 4 separate sources of damage (e.g. damage-spells, melee attacks, explosions, etc), all contributing to the reduction in the target actor's health at time 'n'. It will then be technically possible to let these 4 sources independently activate 4 separate damage-events (called "subDamage_0", "subDamage_1", etc), and then make a rule which sums up their damage numbers and applies the resulting sum to the target.

damage[n](Target, Sum) :-

subDamage_0[n](Target, D0),

subDamage_1[n](Target, D1),

subDamage_2[n](Target, D2),

subDamage_3[n](Target, D3),

add(D0, D1, D2, D3, Sum).We all know that this is silly, of course. The number of sources of damage is not even fixed; there might be five, six, seven, or any indefinite number of instances of damage being applied to the same target at each given moment. Also, we are not sure which sources will be mapped into which "subDamage" events.

If there is a knight and a dwarf attacking the villain at the same time, should the knight's attack be mapped into the "subDamage_0" event and the dwarf's attack be mapped into the "subDamage_1" event? Or the other way around? Or something totally different such as "subDamage_2" and "subDamage_3"? How shall we even guarantee that there will never be two or more attackers who happen to be invoking the same exact "subDamage" event? If that happens to be the case, won't only one of their attacks be taken as part of the incoming damage and the rest be ignored?

Due to such concerns, we are not really able to come up with a rule which specifies exactly how the individual damages should be added together. We do not khow how many of them there will be, as well as which ones will be mapped into which "subDamage" events, and so on, at any arbitrary moment in time.

Here is a problem scenario which I will be attempting to solve. Let's say that the wizard decided to apply 3 damage-spells to the villain throughout the span of 3 consecutive time steps - from time 5 to time 7.

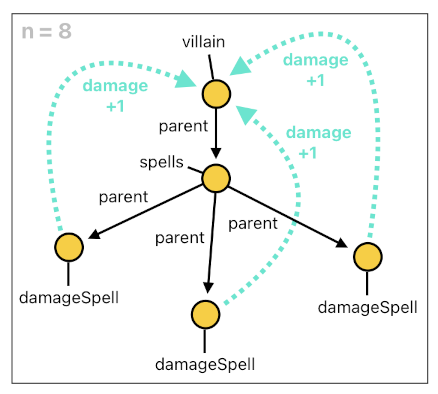

At time 8, then, the villain will be equipped with 3 damage-spells. We know that these spells will all be simultaneously imposing damage upon their common host (i.e. villain), each of them contributing a damage of size 1. So our expectation is that the villain must be receiving 3 damage points at each time step.

This, however, turns out to be not the case. As you can see from the snippet below, these 3 spells all invoke the same exact event called "damage[8](villain, 1)" at time 8 because they are all targeting the same host (i.e. villain) and have the damage strength of 1. In the end, the total damage of 1 will be applied to the villain at time 8 because "damage[8](villain, 1)" was the only event which was being triggered at time 8. The fact that it was triggered multiple times via multiple sources does not make any difference from Prolog's point of view.

damage[8](villain, 1) :-

damageSpell[8](6_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](spells, 6_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](villain, spells).

damage[8](villain, 1) :-

damageSpell[8](7_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](spells, 7_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](villain, spells).

damage[8](villain, 1) :-

damageSpell[8](8_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](spells, 8_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](villain, spells).

FINAL RESULT ---> damage[8](villain, 1).The problem is that the total amount of damage (i.e. second argument of "damage[8](...)") does not increment each time one of the 3 spells raises the event: "damage[8](villain, 1)".

This means that we need to somehow "enhance" the language of Prolog a bit in order to be able to implement such a cumulative effect. The goal is this: We need to come up with a way to accumulate (i.e. add up) one of the arguments of an event, even if it gets called repeatedly during the same exact time step.

And for the purpose of allowing this new feature, I will simply come up with a new attribute (i.e. special keyword) for an argument inside a Prolog relation. It is denoted by "[acc]" (stands for "accumulate"), and can be attached in front of any numerical argument. So for example, the damage-spell's logic can be adjusted to look like the one shown below:

damage[n](Target, [acc]1) :- damageSpell[n](Id), parent[n](S, Id), parent[n](Target, S).This is the same exact rule as the one demonstrated before, except that now the second parameter of the "damage" event (i.e. damage amount) is prefixed by "[acc]". It basically orders the Prolog system to keep accumulating this number during the current time step, while it is evaluating the rules. Only after the end of the clock cycle, this number will be reset to 0.

The following snippet shows the result of the fix. As you can see, the amount of damage which is to be applied to the villain accumulates itself over the sequence of the "damage" event calls. The first spell increases the amount from 0 (initial value) to 1, the second spell increases the amount from 1 to 2, and the third spell increases the amount from 2 to 3. The net result is 3, which means that the villain's health will be reduced by the amount of 3 by the end of time step 8.

damage[8](villain, [acc]1) :-

damageSpell[8](6_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](spells, 6_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](villain, spells).

damage[8](villain, [acc]2) :-

damageSpell[8](7_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](spells, 7_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](villain, spells).

damage[8](villain, [acc]3) :-

damageSpell[8](8_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](spells, 8_wizard&villain_addDamageSpell),

parent[8](villain, spells).

FINAL RESULT ---> damage[8](villain, [acc]3).(Will be continued in Part 14)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service