Author: Youngjin Kang Date: August 22, 2024

Relations are everywhere - from discrete mathematics to computer science, from topology to data science, and innumerable other subjects. In popular areas of research such as ML (Machine Learning) and AI (Artificial Intelligence), too, relations serve as some of the most essential components of logic.

One of the problems in the study of relations, though, is the matter of representing them in a visually intelligible way. While it is possible to express any n-ary relations (for any positive integer 'n') in the form of algebraic notations (such as "xRy", "R(x,y)") or relational data table entries (such as those in an SQL database), expressing them in terms of graphical elements has been a major challenge.

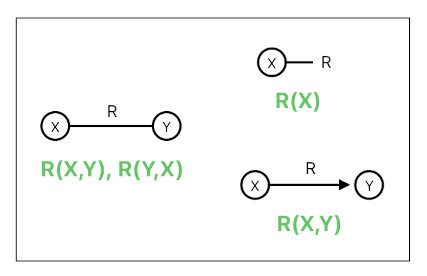

When it comes to graphically depicting unary and binary relations, graph theory comes in handy. As long as we suppose that a relation is an edge and a member of a relation is a vertex, it can simply be assumed that a binary relation is an edge which connects its two members. If the relation is symmetric, it will be a undirected edge (because direction won't matter). if the relation is asymmetric, it will be a directed edge.

Similarly, an unary relation could be rendered as though it is a special case of a binary relation - that is, an edge which connects its sole member to an entity which symbolizes the absence of the other member (i.e. null).

Now, how about ternary relations, quaternary relations, and other n-ary relations, whose arities are higher than two? It is technically possible to use the language of hypergraph (instead of just plain old graph) in which we may be free to express a relation as a hyperedge (i.e. edge with more than two vertices), and so on. We may even be able to describe the asymmetry of such a relation using the idea of a directed hyperedge.

However, a graphical representation of a hypergraph is visually too intimidating, as it no longer allows us to draw a relation simply as a line segment and instead forces us to draw colored regions, bundles of curved arrows, and a myriad of other complex visual elements. This will bloat the viewer's mind with too much abstract information.

In order to be able to draw n-ary relations in a simple, highly recognizable visual language, we must abstain from utilizing conceptual models which are way too abstruse for laymen to understand.

A hypergraph is not something which a person whose area of expertise does not considerably intersect with the domain of pure mathematics is expected to grasp easily. A graph, on the other hand, is something pretty much anyone is able to comprehend at least on a superficial level.

Therefore, it will be helpful for expressive purposes if we somehow figure out a way to represent any arbitrary n-ary relations using the rudimentary graph elements only (i.e. edges and vertices), without leveraging additional layers of abstraction. Also, it will be even more desirable to avoid directed edges and only employ undirected edges (i.e. line segments with no arrow signs whatsoever) so as to ensure utmost structural simplicity.

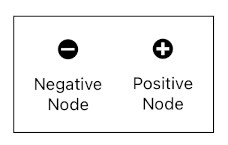

For the purpose of accomplishing the above goals, let me first introduce two basic building blocks - negative nodes and positive nodes (shown above). These two types of nodes, when combined, will be able to constitute the body of any n-ary relation. I will explain the underlying reason shortly.

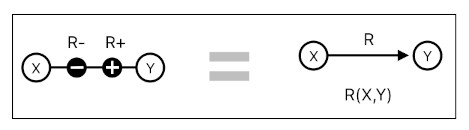

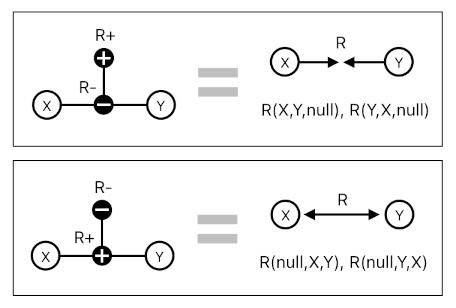

The picture below is our first example of how negative and positive nodes can be used as building blocks of a relation. What you are seeing here is a binary asymmetric relation with two member variables: X and Y. If we were using a directed graph, we would only need a directed edge (i.e. arrow) to depict such a relation. Since we are trying to describe it using an undirected graph, however, we need at least two distinct types of connected nodes between X and Y to express the sense of directionality from X to Y (I am assuming here that the relation's "direction" goes from negative to positive).

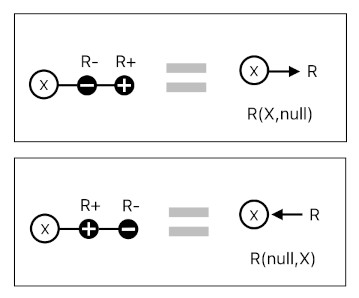

What if there is no Y, and we are only left with X? There may be two opposing scenarios (demonstrated in the image below).

If X were connected to the negative side, the pair of nodes would be a quasi-unary relation which "points away from" X (i.e. points from X to nowhere). If X were connected to the positive side, the pair of nodes would be a quasi-unary relation which "points toward" X (i.e. points from nowhere to X). In both cases, the pair of nodes characterizes an unary relation whose sole member is X. Its "direction" in regard to X is a highly nuanced feature whose usage depends on the application.

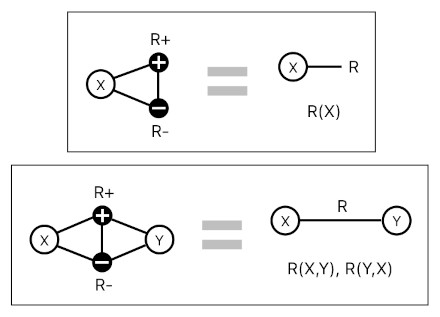

What if we do have both X and Y as members of the relation, yet both of them are attached to only one of the relation's pair of nodes? The image below illustrates two possible scenarios.

If X and Y were connected to the negative side, the pair of nodes would be a quasi-binary relation which "points away from" both X and Y (i.e. points from X,Y to nowhere). If X and Y were connected to the positive side, the pair of nodes would be a quasi-binary relation which "points toward" both X and Y (i.e. points from nowhere to X,Y). In both cases, the pair of nodes characterizes a binary symmetric relation whose members are X and Y (It is symmetric because there is nothing which enforces an order between X and Y). Just like in the previous case, its "direction" in regard to X and Y is a highly nuanced feature whose usage depends on the application.

In the language of bidirected graphs, these two cases may be interpreted as an "introverted edge" and an "extraverted edge", respectively (See Bidirected Graph).

So far, I have only demonstrated relations which possess their own directions (i.e. asymmetry). It is, however, also feasible to construct a symmetric relation if we model it as though it is a pair of asymmetric relations pointing in two opposite directions. Its unary and binary examples are showcased below.

Just like before, we are presuming here that each relation is a connected pair of dual particles (i.e. negative node and positive node). Recall the previous examples, and see how the new ones differ from them.

Suppose that X is the only member of the relation. If X is connected to both the negative and positive sides, we will be able to say that the relation points both toward and away from X. This means that it is an unary relation which associates itself with X without specifying any particular direction in regard to it.

Suppose, on the other hand, that X and Y are both members of the relation. If X and Y are simultaneously connected to both the negative and positive sides, we will be able to say that the relation points both toward and away from X and Y. This means that it is a binary relation which associates itself with X and Y without specifying any particular direction between them.

The main benefit of using dual (negative and positive) nodes as means of formulating relations can be found in the case of n-ary relations, where 'n' is an arbitrary integer which is greater than 2.

Traditionally, it has been presumed that only binary relations can adequately be rendered in the standard graph notation (i.e. edges and vertices). What I would like to suggest in this article is that, by means of negative and positive nodes, it is possible to represent even an n-ary relation (where n > 2) in a plain undirected graph (That is, by drawing only dots and lines on a sheet of paper, along with a bit of symbolic characters such as '-', '+', and alphanumerics).

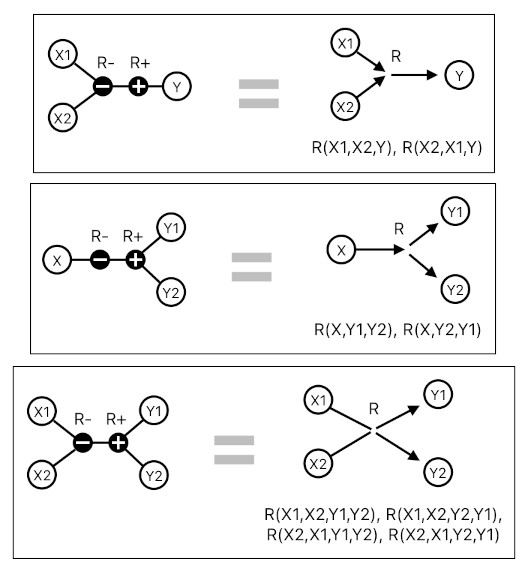

The image below shows three examples of the idea I just mentioned, the first two being ternary relations and the last one being a quaternary relation.

The first case depicts an instance of "merge" - i.e. a scenario in which two separate things (X1,X2) merge into one thing (Y). The order of the things which are being merged does not matter, so this relation is symmetric with respect to X1 and X2.

The second case depicts an instance of "split" - i.e. a scenario in which one thing (X) splits into two things (Y1,Y2). The order of the things which are being produced by the split does not matter, so this relation is symmetric with respect to Y1 and Y2.

The third case depicts an instance of "exchange" - i.e. a scenario in which two things (X1,X2) interact with each other, exchange resources, and end up turning themselves into a pair of things (Y1,Y2) which are somewhat different from the previous two. Since this particular act of exchange does not imply a sense of directionality from one thing to the other, this relation is symmetric with respect to both the former pair (X1,X2) and the latter pair (Y1,Y2).

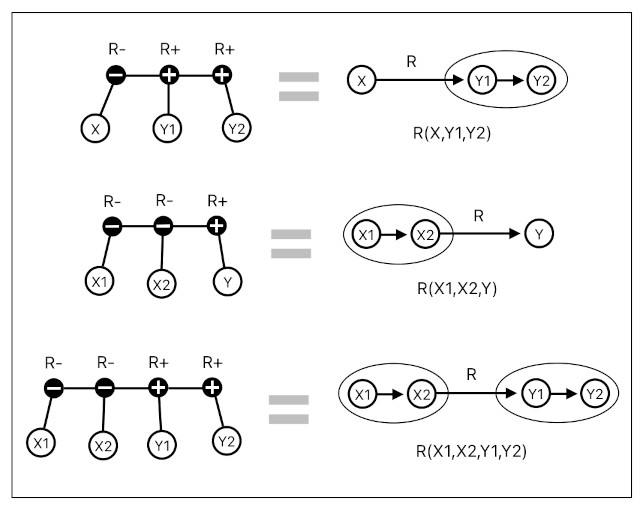

What about n-ary relations which require a fixed order between its members? The image below illustrates ways in which such a strict sense of asymmetry can be achieved.

The first case indicates an instance of "split", yet the outcome of the split is a vector of two components (Y1,Y2) instead of a set. Here, the order between Y1 and Y2 is being enforced by the order in which the two positive nodes are connected with respect to the negative node.

The second case indicates an instance of "merge", yet the ingredients of the merging process is a vector of two components (X1,X2) instead of a set. Here, the order between X1 and X2 is being enforced by the order in which the two negative nodes are connected with respect to the positive node.

In general, it is definitely feasible to construct any arbitrary n-ary relation and selectively make parts of its list of members either symmetric or asymmetric, by means of dual (negative and positive) nodes connected in series. The number of connected negative (or positive) nodes will imply the number of members in a group whose order is strictly enforced (as though they are elements of a vector), and the number of parallel connections to each negative (or positive) node will imply the number of members in a group whose order does not matter (as though they are elements of a set).

Visualization is not the only advantage which can be gained by the aforementioned methodology. One of the upsides of modeling a concept in the form of a plain undirected graph (instead of something fancy such as hypergraph) is that it can easily be translated into a physical equivalent such as an electric circuit (which is useful for applications in science/engineering).

A vertex or a connected set of vertices, for example, can be modeled as a circuit component (e.g. logic gate, amplifier, buffer, arithmetic module, memory module, etc), and an undirected edge can be modeled as a wire which establishes an electrical connection between a pair of circuit components.

If engineers happen to desire to create a specialized computational system (such as a custom circuit) which uses relations as its basic unit of computation, therefore, they will find the nodal representation of n-ary relations to be a helpful means of devising a piece of hardware in which each relation is implemented not as a piece of abstract data inside a random-access array, but as a real physical device which occupies an area on the circuit board.

This kind of implementation will be optimal for interpreting a logic programming language such as Prolog, which is based upon relations and their mappings (i.e. horn clauses).

1. The Origin of Reality - Volume 4

2. The Origin of Reality - Volume 7

3. 연결의 종류 (Korean)

4. 이진법적 공간의 배열 (Korean)

5. 공간의 근본적 형태들 (Korean)

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service