Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 24, 2023

(Continued from volume 6)

In the previous volume, it was clearly demonstrated that at least the facade of our reality is capable of being modelled as a sequence of abstraction layers, whose direction of divergence corresponds to the process of specification and whose direction of convergence corresponds to the process of generalization.

It was also suggested that, due to the possibility of composition among qualities, each layer of abstraction gives birth to a bipartite graph which topologically resembles that of a neural network.

It will be too rash to conclude, however, that such a directed arrangement of ideas and their associations completes the full picture of what reality is made out of.

First of all, the conceptual bridges I have been laying down in the recent example (e.g. black cat, white cat, etc) are quite suspiciously adduced by intuition and therefore should be deemed too inappropriate to constitute a legitimate portion of our system of logic.

If someone asks me to explain the choice I have been making from a common sense point of view, I will confidently say that a black cat and a white cat are both cats and therefore they both deserve to be associated with the idea "cat". But if someone asks me to prove why such a choice must be correct, I will probably have to consult the virtue of statistics and say that I made such a decision because the majority of people agree that it is a decent way of grouping ideas together.

Yet this methodology can hardly avoid the accusation that it is based upon a set of arbitrary assumptions, one of which is: "The majority's opinion is the right opinion". And you know that the usual fate of populism is mediocracy, as well as that there is no particular reason to believe that the position of truth coincides with the center of mass of our collective body of knowledge.

The root of the problem of subjectivity lies on the very definition of association itself. So far, I have been implicitly supposing that two ideas are "associated" if conceiving one of them lets me conceive the other. And this kind of formulation is pretty fuzzy in the sense that the phenomenon of conception is not so satisfactorily consistent outside of the domain of experimental psychology (e.g. causal relation between stimulus and reflex).

Thus in order to build a clear foundation of reason, it is crucial to transcend the semantic ambiguity of our raw ingredients called "associations" and begin thinking in higher dimensions.

As soon as we notice that ideas are able to establish connections with one another, one must take into account the possibility that these things could represent different types of relations. The biggest challenge here is in figuring out how many types there are and how they should be defined.

Before trying to come up with rather specific examples (so as not to trap ourselves inside a mud pool of mere wordplay), one's got to first devise a structural basis upon which subsequent thought experiments acquire their opportunities to participate. And for this purpose, let us start by recognizing some of the common patterns which are being exhibited by what we typically refer to as "relations".

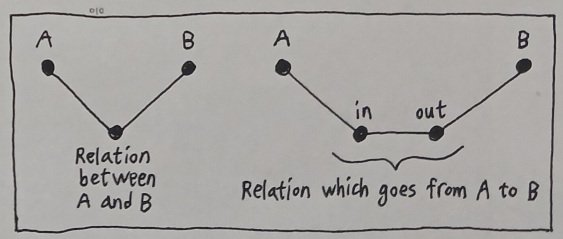

Love of minimalism hints us that there are two major categories of relations - undirected and directed.

If we imagine that there are two ideas called "A" and "B", we will be able to declare that there is a relation between A and B which does not depend on the order in which these two subjects are being treated (such as "A and B are in the same group" or "A and B are close to each other"). This order-independence allows it to be represented by a single intermediary idea which functions as a stepping stone between A and B.

We can also envision a relation whose definition depends on the order between A and B (such as "A comes before B" or "B sends a message to A"). We need to denote this sort of relation by a pair of intermediary ideas instead of just one, for the purpose of giving directionality to it.

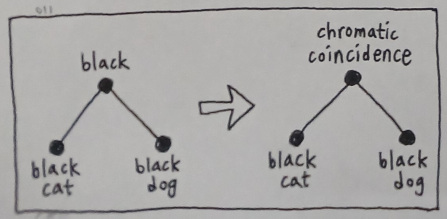

Let us revisit the scenery of the previous example and suppose that there are two ideas called "black cat" and "black dog". Intuition tells us that these two are both associated with the idea "black", yet our thirst for logical clarity also renders it necessary to identify "black" as a functional binding point rather than a hazy stockroom of "some things here and there that look like they should be put together".

The idea "black" combines "black cat" and "black dog" into the same group, based on the premise that they share a relation which could be illustrated as "chromatic coincidence".

In this interpretation, we may as well say that "black" is not just an idea, but also a relation which binds "black cat" and "black dog" together based upon their proximity in color space. Whether this proximity is sufficiently high as to justify the existence of such a relation does introduce a bit of room for subjectivity, yet it is not so hard to defer the necessity to resolve such a problem by simply fantasizing that there is only one absolute threshold somewhere in the universe which tells us exactly how much closeness is "close enough".

(Will be continued in volume 8)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service