Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 18, 2023

(Continued from volume 3)

In the last volume, I suggested the utilization of what are supposedly the most fundamental (indivisible) constituents of reality, which I referred to as "thoughts".

But for the sake of detaching them from the widely accepted yet subjective understanding of what "thoughts" are (e.g. brain activities, etc), I will henceforth start denoting these hypothetical entities by the term "ideas" instead.

It has been assumed that ideas, as long as one's faculty of reasoning declares that no process of logic can possibly involve a parameter which is unable to be broken down to a composition of ideas, must be considered "real" regardless of their inner or outer characteristics. It is because we are trying to come up with a definition of reality here, and such a definition must be derived logically from preceding ones which ultimately trace back to mere declaration of ideas.

Therefore, we will begin by coming up with a sound method of denoting the availability of ideas and a way in which they can be synthesized with one another for the purpose of revealing more variety of patterns. The first axiom to kickstart the whole line of argument is:

"Any arbitrary expression is an idea."

This means that, no matter which expression we choose to speak in our language, it automatically counts as an idea (because in order to express something, the speaker must think about it). Another axiom which must hold in order to assert the validity of its being is:

"Any idea is a fact."

In our worldview, any idea is a "fact" regardless of the context to which it belongs. It is not an intermediary bridge aimed to serve a purpose, nor does it oblige itself to mean anything; it just "is".

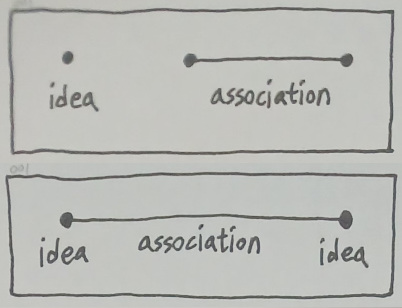

Now here is another primitive building block that is needed to let us formulate patterns out of individual ideas - "association". Ideas themselves are nothing more than instances of nil floating in the midst of nowhere; it is only when they associate themselves with one another that they begin to introduce more syntax than a set of isolated points. We henceforth assume here that there must be not just one, but two primitive data types in the grammar of reality - ideas and their associations.

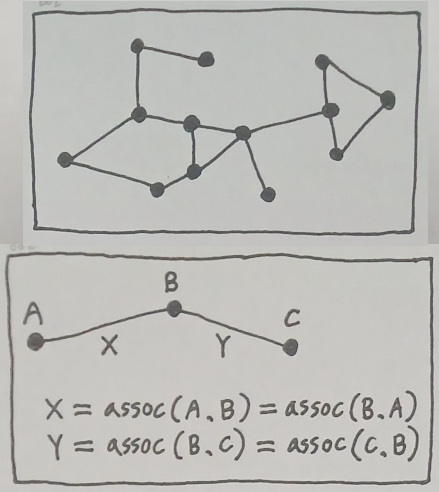

In the context of mathematics, one can quite reasonably imagine that the domain of knowledge which is being represented here resembles that of graph theory, in the sense that each idea is an equivalent of a vertex and each association is an equivalent of an edge connecting a pair of vertices.

And this apparent resemblance may prompt some of those enthusiastic mathematicians in academia to insist that the model of reality I am proposing in this writing is nothing more than a mere reiteration of what has already been researched in the field of mathematics as well as other academic disciplines which depend on the language of graphs.

But before being so quick to ejaculate such a preemptive judgement for the purpose of not letting me hurt the feeling of an army of professional student loan consumers, one's got to behold that analyzing the properties of a graph is not the goal we are aiming for; it is just a convenient tool for demonstrating one's route of reason, just as a finger can be utilized to indicate the Moon without having to be the Moon itself.

Another potential objection which may come to surface is that, since I am initiating a whole stream of thoughts based upon a graph-based language, pretty much every one of its ensuing logical conclusions will still be confined to the boundary of graph theory. This may certainly be a valid point to some extent, yet I would argue that if such a side of reasoning is universally applicable without a single exception, it must also be okay to claim that the theory of finite state machines reveals no more knowledge than what a random graph can disclose due to the fact that such machines can be depicted in terms of state diagrams (i.e. directed graphs).

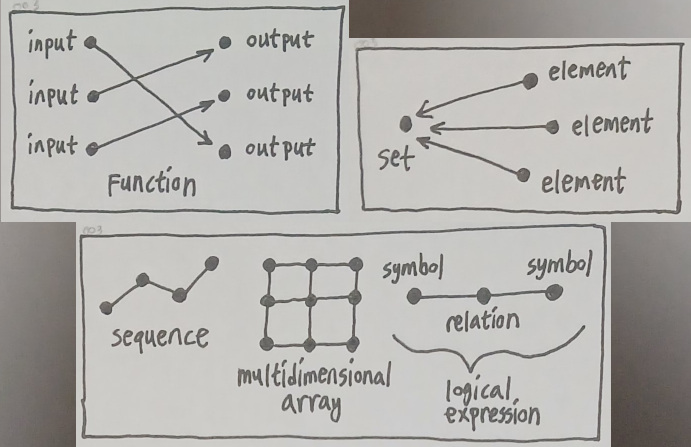

Here is yet another question which might be raised. And that is: "Why graphs in particular?". Why not use sets, algebraic formulas, logical operators, vectors, matrices, geometric figures, computer algorithms, and myriads of other ways of outlining quantitative concepts?

The reason for choosing the language of graphs is that it is probably the most comprehensive medium of illustration when it comes to pure concepts, including those in mathematics.

A function is just a bunch of input values being mapped to their respective output values, so it is something we can represent as a bipartite graph in which each edge denotes a mapping relation. A set is just a bunch of parent-child relations between itself and its children (i.e. elements), which can be depicted by a graph. A sequence? It is a graph made up of a chain of elements. A matrix? It is just a group of elements arranged in a mesh-like graph. A tree? It is just a graph without a loop. An algebraic expression? It is basically an expression tree, so it is a graph, too. A geometric shape? It is a graph consisting of a bunch of spatial points (vertices) and line segments (edges). A logical statement? It is just a pile of symbols and their relations, which can all be expressed in terms of vertices and edges. The list goes on.

(Will be continued in volume 5)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service