Author: Youngjin Kang Date: December 13, 2025

This article is Part 29 of the series, "Linear Algebra for Game Development". If you haven't, please read Part 1 first.

So far, we have seen how the system may analyze the way in which objects are related to one another, as well as trigger interactions which fit the narratives of those relations.

There is one major scalability issue here, though. What if the game world is so colossal and heavily populated, that processing the entire network of relations is bound to put too much computational burden on a single device?

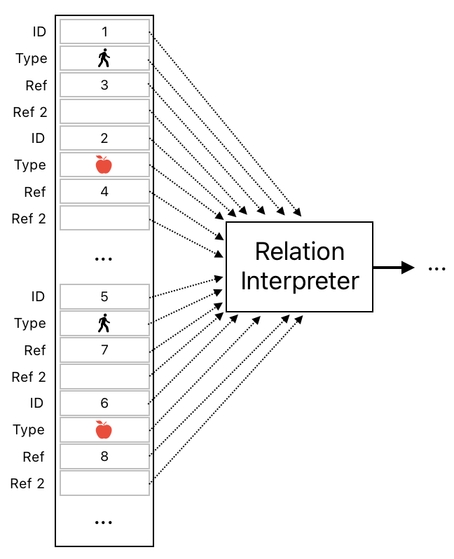

The following example illustrates why the current scheme does not scale well. Suppose that there are two players and two apples, instead of just one player and one apple.

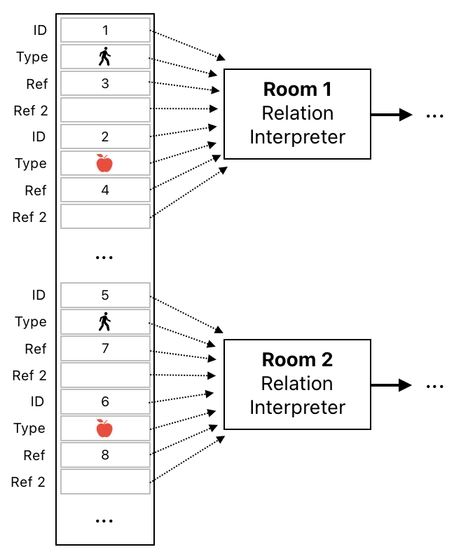

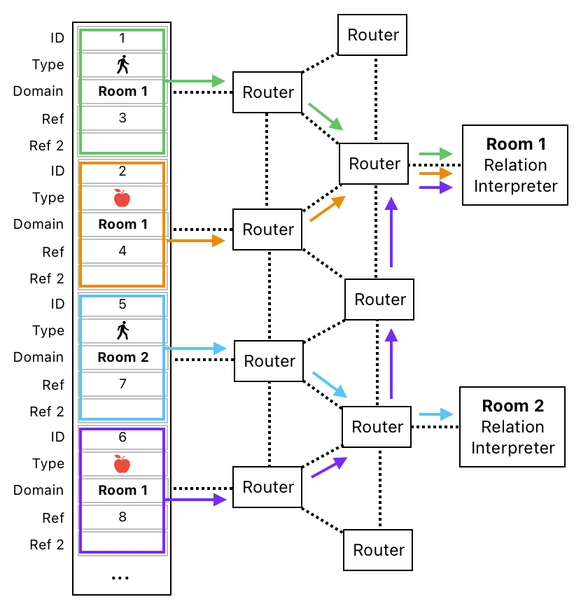

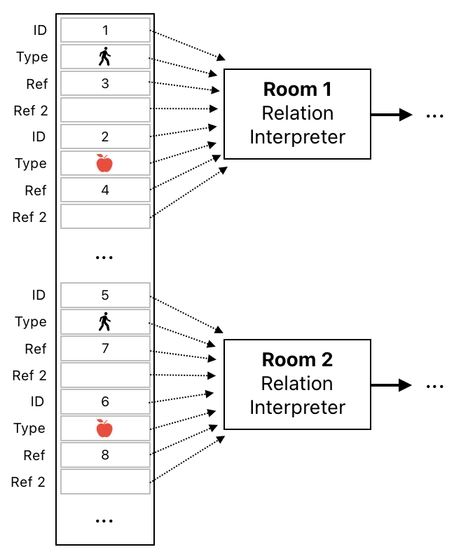

As long as we rely on a single module to process all 4 of them, we will have a system which looks like what is shown below. Notice that a single electronic device ("Relation Interpreter") is responsible for scanning the entire data table and analyzing all of their relations simultaneously.

This is way too much for for a single device, and it somewhat violates the single responsibility principle. In order to reduce computational cost and enhance structural simplicity, we better split the workload into smaller pieces and distribute them across multiple modules.

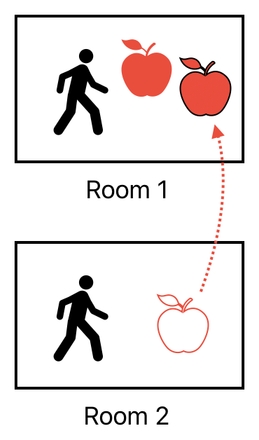

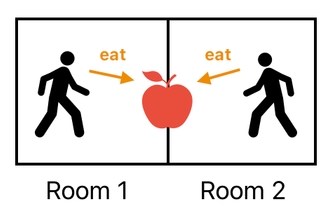

So, for example, let us imagine that there are two separate "rooms" in our game world, each of which contains a player and an apple. They are called "Room 1" and "Room 2", respectively.

Room 1 and Room 2 are completely isolated from each other; that is, anything in Room 1 cannot possibly interact with anything in Room 2, and vice versa.

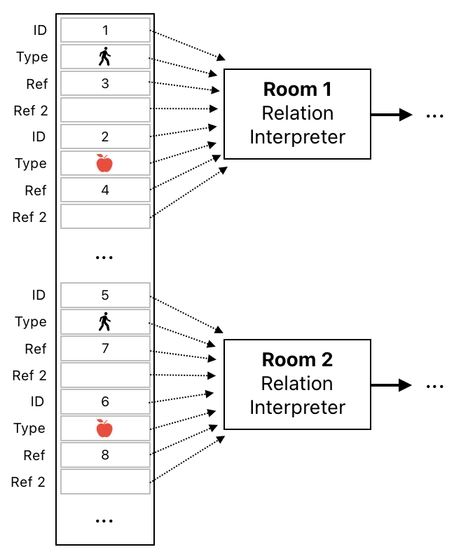

Given such a precondition, what sort of conclusion are we able to make? One thing which may cross your mind, is the fact that all the events happening in Room 1 can be inferred from relations in Room 1 only, and that all the events happening in Room 2 can be inferred from relations in Room 2 only.

This means that two separate modules (relation interpreters) can be used to compute transactions in each of these two rooms.

Of course, such a clear and permanent sort of insulation is not to be expected in most gameplay scenarios. At some point, we should allow some of the objects in one room to move over to another room, so as to be able to interact with things outside of their own room.

For instance, it should be possible for us to let the apple in Room 2 jump over to Room 1 (for whatever reason).

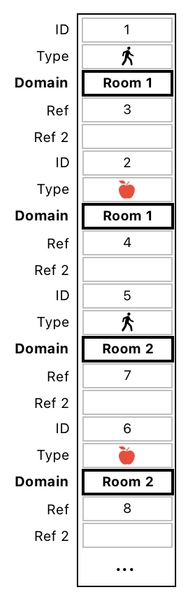

How to represent this kind of phenomenon in our data table? First, we should imagine each room as its own isolated "domain" - a volume in space which does not overlap with any of the other volumes. Each object in our game world, then, should be assumed to reside in one of the existing domains, implying that it is reasonable to include "domain" as one of the data entries which are allocated to each object.

Here, you can see that the table's first pair of objects belong to Room 1, and the second pair of objects belong to Room 2.

When the apple in Room 2 wants to jump over to Room 1, all we need to do is just change its domain value from "Room 2" to "Room 1", as illustrated below.

This will tell the system that the apple, which used to reside in Room 2, is now in Room 1.

From a technical perspective, though, there is a problem which must be resolved.

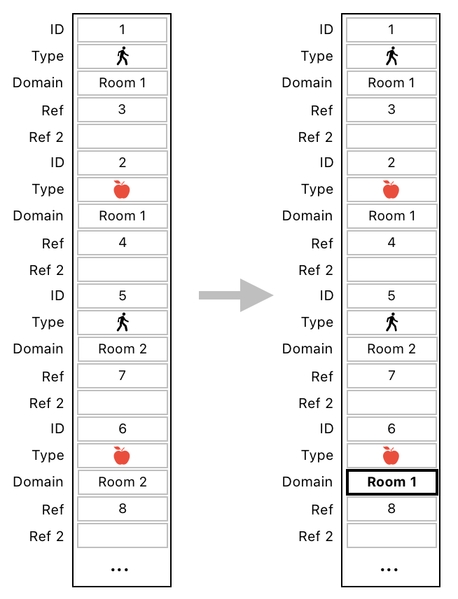

I have previously mentioned that each room can have its own separate module to handle all of its relations as well as their resulting interactions.

This will be pretty straightforward as long as objects never move from one room to another. In such a case, we could just split our data table into two groups of rows, where the first group belongs to Room 1 and the second group belongs to Room 2. On a hardware level, these two will simply be two separate physical regions on the circuit board.

Since we are supposed to allow an object to change its room, however, we ought to employ a more dynamic approach.

For example, we might consider having a network of routers which, like the internet (or postal service), delivers packets of information from place to place based upon the recipient's address.

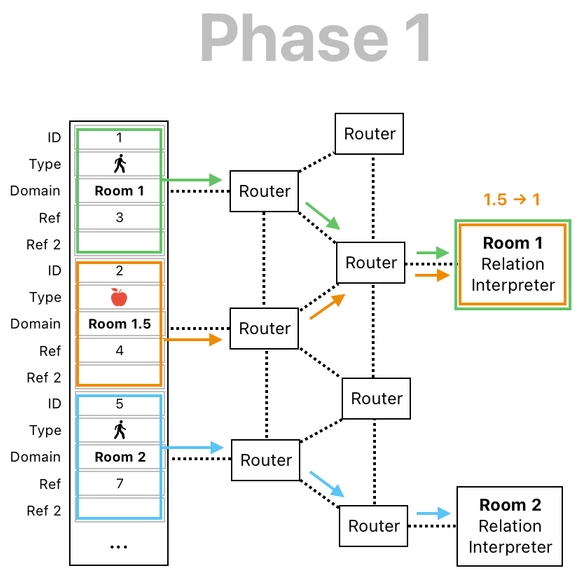

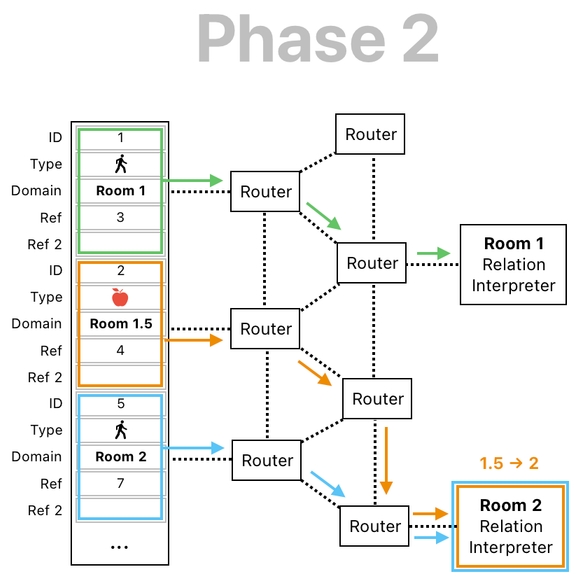

In our case, there are two potential recipients - Room 1 interpreter and Room 2 interpreter. If a block of entries in our data table (aka "object") belongs to Room 1 (i.e. its domain is set to "Room 1"), such a block will be delivered to Room 1 interpreter. If the block belongs to Room 2, on the other hand, it will be sent over to Room 2 interpreter instead.

It is common in the context of gameplay, however, that spaces are not nearly as isolated from one another as the ones depicted above.

While it is reasonable to imagine that objects in two different rooms do not usually interact with each other, it is not that difficult to imagine a scenario in which an interaction occurs right at the boundary between a pair of adjacent rooms.

For example, we could easily suppose that there is an apple sitting at the threshold between Room 1 and Room 2, and that two players, one in Room 1 and the other one in Room 2, are simultaneously eating this apple together.

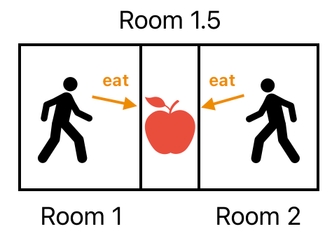

How shall we simulate this kind of phenomenon? One thing which is quite obvious is that the apple in this case neither exclusively belongs to Room 1 nor Room 2; rather, it sits "in the middle" between the two rooms. Let us refer to this middle point as "Room 1.5" (because, you know, 1.5 is in the middle between 1 and 2).

The problem we are facing is that there are two interactions happening. One of them takes place between Room 1 and Room 1.5, and the other one takes place between Room 2 and Room 1.5. This implies that, when it comes to eating the apple in Room 1.5, BOTH Room 1 and Room 2 must be involved.

This is problematic, as it no longer allows us to process Room 1 and Room 2 separately (in the manner illustrated below).

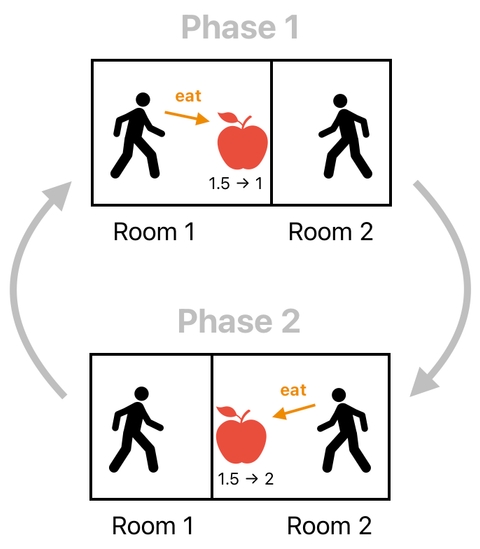

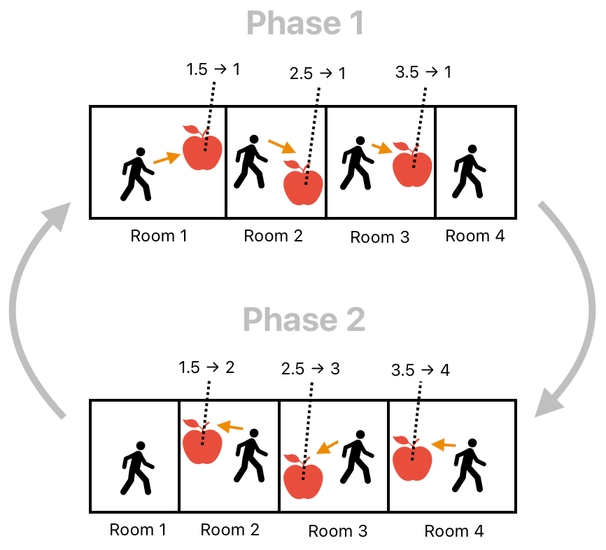

There is a way to circumvent this, fortunately. Instead of trying to handle both interactions at once, we can first split the game's update loop into two phases (i.e. "Phase 1" and "Phase 2") and then periodically alternate between these two.

Phase 1 -> Phase 2 -> Phase 1 -> Phase 2 -> Phase 1 -> ...

Let me explain how it works.

In Phase 1, we will pretend that Room 1.5 is the same thing as Room 1 (i.e. that the apple exclusively belongs to Room 1). In this phase, therefore, only the player in Room 1 will eat the apple. The player in Room 2 will not be able to eat the apple because he is in a different room.

In Phase 2, on the other hand, we will pretend that Room 1.5 is the same thing as Room 2 (i.e. that the apple exclusively belongs to Room 2). In this phase, therefore, only the player in Room 2 will eat the apple. The player in Room 1 will not be able to eat the apple because he is in a different room.

As you may have guessed already, the execution of both Phase 1 and Phase 2 will ensure that both of the players in Room 1 and Room 2 will each have a chance to eat the same apple. Instead of eating it exactly at the same moment, though, they will simply "take turns" eating it, one bite at a time.

Here is how the apple's data will be routed during Phase 1 (See the image below). During Phase 1, the number "1.5" gets rounded down to "1", thereby letting Room 1.5's objects be sent over to Room 1's interpreter. This allows the apple to interact with objects in Room 1.

And here is how the apple's data will be routed during Phase 2 (See the image below). During Phase 2, the number "1.5" gets rounded up to "2", thereby letting Room 1.5's objects be sent over to Room 2's interpreter. This allows the apple to interact with objects in Room 2.

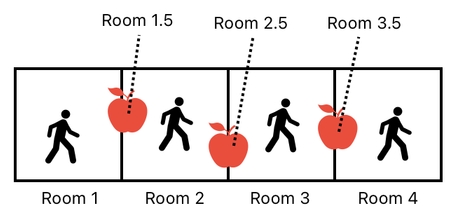

In general, this multi-phase approach can be applied to not just a single pair of rooms, but a vast array of regions in space which, when arranged side-by-side, constitute a vast open area.

And the truth is that the aforementioned logic applies just as well to such a general case (Check out the diagram below to see how it works).

For more information on how to handle continuous space in a modular manner, please read: Parallel Adjacent-Cell Modification Support for General-Purpose Cellular Automata.

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service