Author: Youngjin Kang Date: December 5, 2025

This article is Part 28 of the series, "Linear Algebra for Game Development". If you haven't, please read Part 1 first.

A matrix is all we need to carry out a transaction.

Each transaction matrix is capable of executing a bunch of actions in parallel, each of which is made up of simple additions and multiplications (i.e. linear combinations).

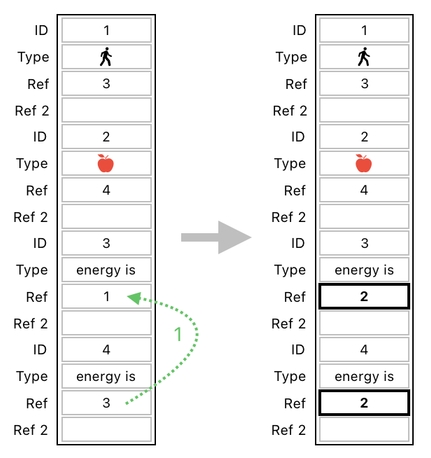

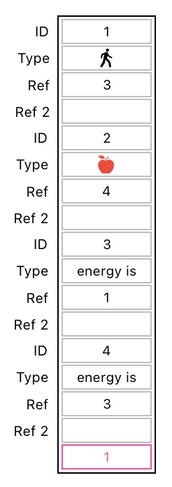

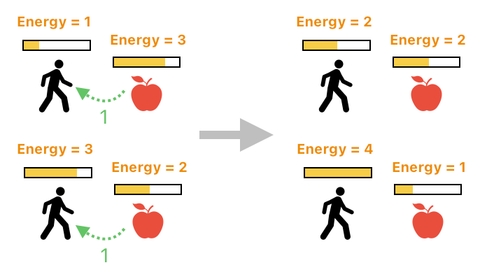

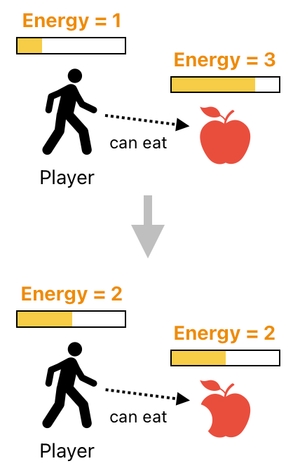

In our previous example, we saw that it is fairly straightforward to simulate a simple energy exchange between a pair of agents. For instance, if we wish to take away 1 energy point from the apple and give it to the player (as shown in the picture below),

all we will need to do is multiply the table by a transaction matrix which looks like this:

Such a matrix works flawlessly in our particular circumstance. However, we must also be aware of the fact that it requires us to place our parameters (i.e. energy values) in predetermined locations. The matrix above, for example, expects us to specify the player's energy in the 11th row of the table and the apple's energy in the 15th row of the table.

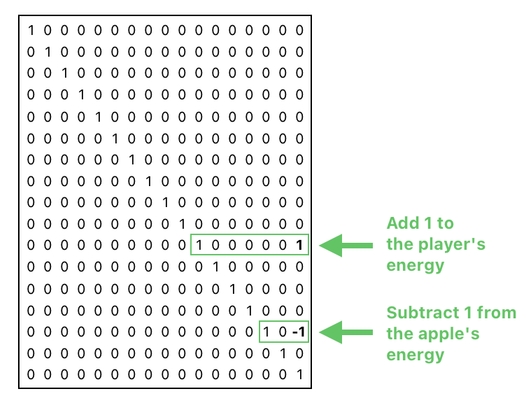

If the data entries were ordered in some other way (like the ones displayed below),

the rows in the transaction matrix would have to be rearranged to reflect such a difference.

This is rather inconvenient, since it implies that the matrix needs to be redesigned every time our table gets modified even by a tiny bit.

Fortunately, there is an elegant way to solve this problem. All we have to do is stop letting our transaction matrix depend upon the manner in which the table's elements are arranged.

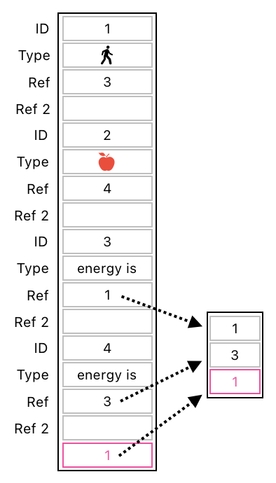

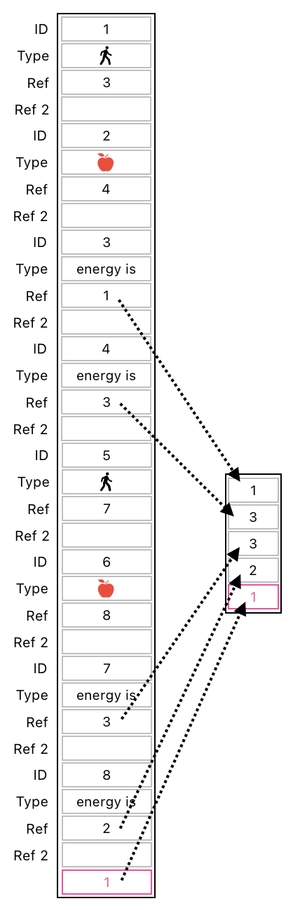

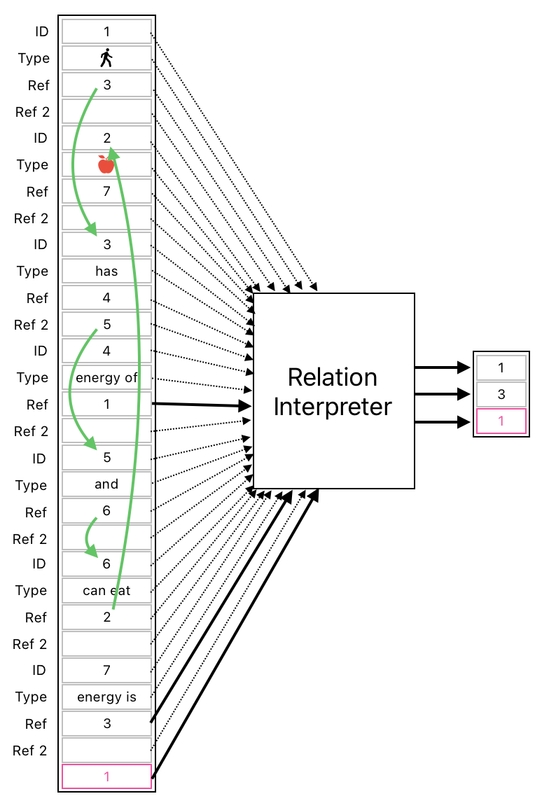

Let me demonstrate what I mean by this. When you look at the table below, which data entries do you think will need to be modified in order to transfer 1 energy point from the apple to the player?

Without a doubt, you would say that the 11th and 15th elements of the table will need to be modified. The former should increase by 1, whereas the latter should decrease by 1.

When designing a transaction matrix for this kind of exchange, therefore, we do not really need to care about most of the entries in our table. All we need to care about is the table's 11th element (i.e. player's energy), 15th element (i.e. apple's energy), and the "1" at the very bottom of the table for defining the rate of exchange.

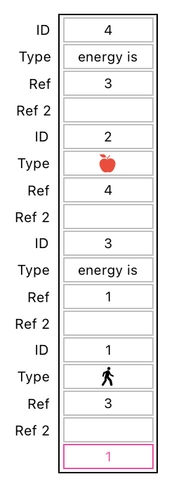

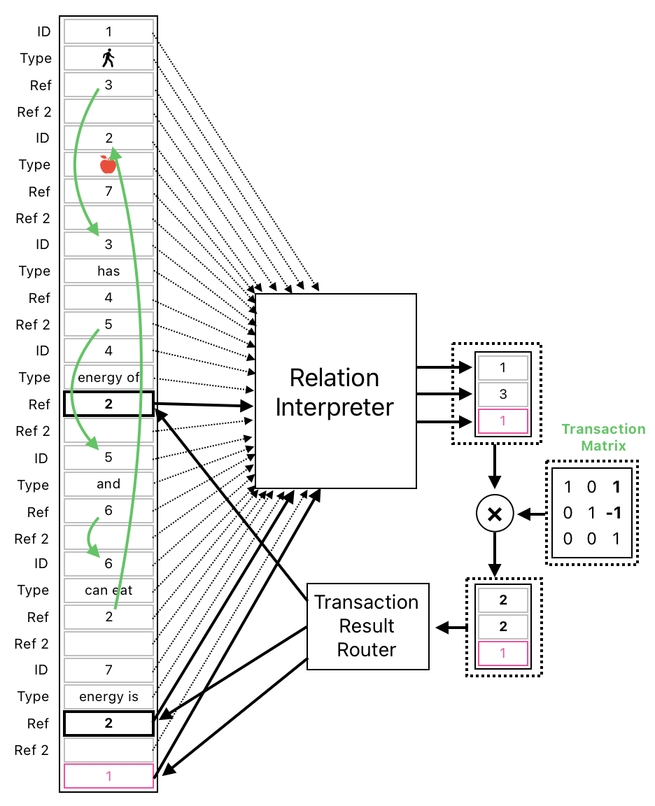

So, why don't we just extract these 3 elements from our table and put them in a much smaller table which consists of only 3 slots?

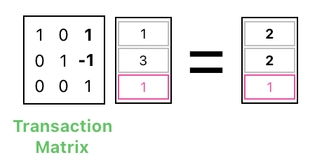

We will then be able to modify the energy values by using a significantly more compact transaction matrix, such as the one illustrated below.

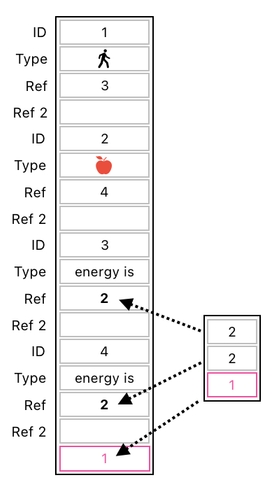

After applying the transaction, we will simply need to bring the elements back to their original locations.

See? Now we have our desired result - the consequence of transferring 1 energy point from the apple to the player.

What I just described is not the end of the story. An even greater advantage of using the aforementioned approach becomes evident as we expand our transaction matrix a bit, making more rooms for additional transactions.

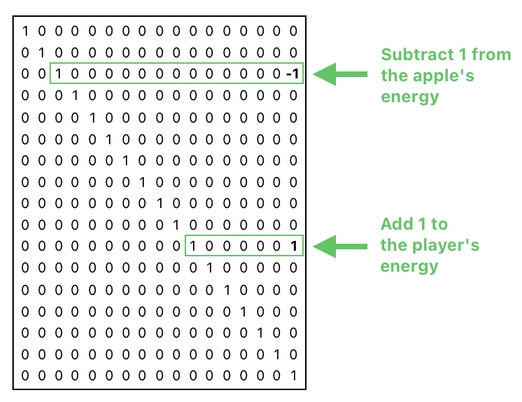

Take a look at the scenario depicted below, where there are two players and two apples. The first player takes a bite from the first apple, thereby stealing 1 energy point from it. Meanwhile, the second player takes a bite from the second apple, thereby stealing 1 energy point from it.

Shall we perform 2 separate transactions to compute the outcomes of these two events? Hell no! The whole point of executing a transaction is to process a bunch of events at once, instead of processing each of them at a time.

Just like we are able to pack multiple arithmetic operations (e.g. increment by 1, decrement by 1, etc) inside a single transaction, we are able to pack multiple transaction inside some kind of "meta-transaction" - a transaction that is made up of transactions.

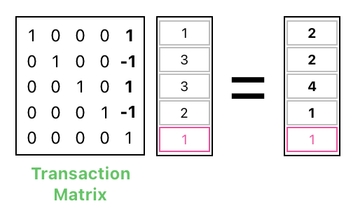

Here is how we do this. First, let us extract the energy values from the two players as well as the two apples, and group them in a tiny table which consists of only 5 elements (See the picture below).

We can then multiply this table by a transaction matrix (shown below) which simultaneously performs 2 energy transfers. One of them takes away 1 energy point from the first apple and gives it to the first player, and the other one takes away 1 energy point from the second apple and gives it to the second player.

Once the calculation is over, the only remaining step is to simply put these results back to their original places.

But of course, what has been explicated so far does not fully cover the intricacies of the system.

For instance, I have not explained how our gameplay algorithm will manage to decide which transactions to carry out, as well as choose the appropriate data entries from the table to use as their parameters.

Thus, it is time for me to elaborate on the nature of conditions which are responsible for invoking transactions in the first place.

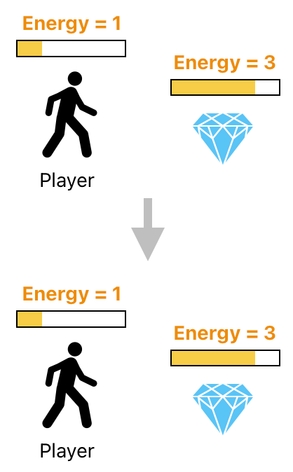

Here is an example. We all know that a diamond is not edible, right? So, even if a diamond is right in front of the player, he is not going to be able to eat it (i.e. absorb energy from it). A transaction which directly transfers energy from the diamond to the player will not make sense for this reason.

On the other hand, we know that the player is able to eat an apple. So, it makes sense to execute a transaction which transfers energy from an apple to the player.

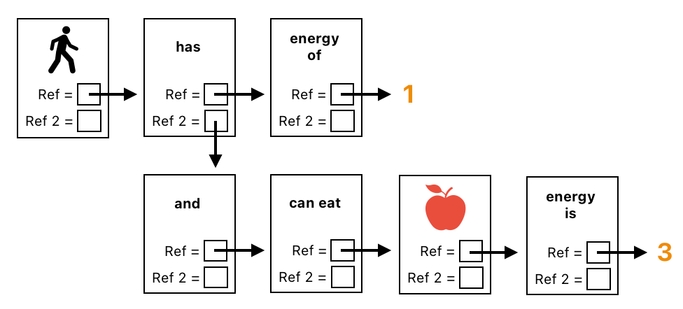

In order to state this fact explicitly, we will need yet another relation called "can eat" whose job is to indicate that the player "can eat" the apple. The diagram below illustrates how such a relation could be configured.

The meaning of the arrows will be quite obvious if you follow them carefully. The result of interpreting them in plain English can be stated as the following:

The player has the energy of 1, and can eat the apple whose energy is 3.Okay, then. The next question is, "How shall we let the system automatically figure out that the player is able to eat the apple?" We must answer this question in order to let the energy-transferring process kick off whenever there are both a player and an apple.

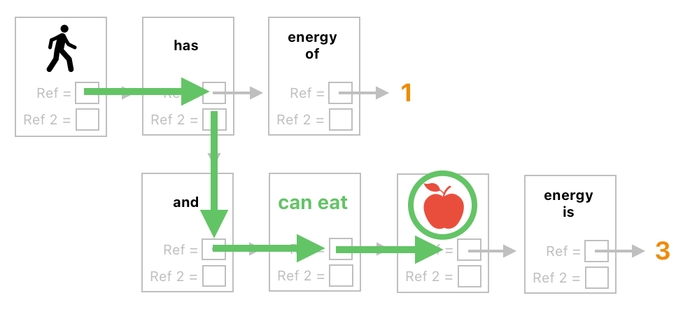

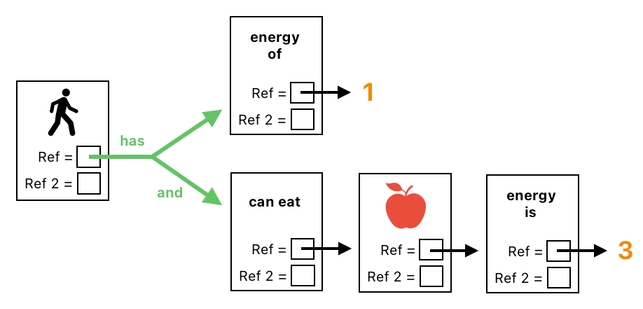

Here is how the line of reasoning may proceed (See the picture below).

As you can see from the green arrows, it is the sense of connection which suggests us that the player "can eat" the apple.

The player "has" something, "and" is also associated with the idea that he "can eat" something else. And this "something else" happens to be the apple. Such a chain of relations leads us to infer the fact that the player is able to eat the apple.

A more intuitive way of understanding this is to imagine the conjunctive relations (i.e. "has", "and") as relays of some kind, since they do nothing more than simply connecting things with together (just like wires in a communication network).

The player is connected to the "energy of" relation by means of the relay called "has". Additionally, the player is also connected to the "can eat" relation by means of 2 relays, "has" and "and", which are connected in series.

The main takeaway from this sort of analysis is the notion that a pattern of relations can be recognized via a simple graph traversal algorithm. All we need is a computing device whose job is to walk through the network of relations, by visiting one relation (i.e. vertex) at a time and recursively visiting its references (i.e. edges).

Such a device, on a hardware level, could be imagined as a tiny electronic module (called "relation interpreter" or something) which scans the data table, derives meaningful associations from it (such as: "The player can eat the apple") by means of graph traversal, and feeds the appropriate parameters into a temporary table.

This temporary table, then, will undergo a transaction (by means of a matrix multiplication), yielding the updated data entries. The resulting entries will then be fed back to their original slots, updating the state of our data table.

Previous Page

Next Page

Previous Page

Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service