Author: Youngjin Kang Date: August 13, 2024

Designing a gameplay system is a fairly complicated job, due to the way in which game mechanics typically work. A game usually involves a variety of factors, which are intertwined with one another in all sorts of dynamic ways. Worse still, a game designer who is not well-versed in software engineering is prone to further compound this kind of complexity by making requests which compel the engineers to break the general rule of the game by introducing special cases, thus convoluting the codebase.

If engineers ever happen to decide that a large portion of the codebase must be refactored in order to meet the designer's unexpected request, they are likely to be accused of "not willing to deliver the product on time". Eventually, those who are deemed "productive" are ones who duct-tape their way around the designer's irrational expectations and shove the accuring tech debt under the rug.

Therefore, engineers who are intelligent enough to comprehend the seriousness of this problem will be quick to realize that there are two ways of solving it; it is either (1) Work with a decent designer who at least has a STEM mindset, or (2) Start developing a system which is so robust, that even the craziest design request cannot ruin it.

The first solution works only if the engineers are able to choose which designer to work with. Unfortunately, this does not usually happen unless they are part of a small indie game studio (in which case the boundary between a designer and an engineer would be pretty blurry anyways).

The second solution, on the other hand, works at least to some extent as long as those in charge of shaping the overall architecture of the system are engineers, not "coders". A person who knows how to write code in more than a myriad of programming languages and has memorized a bunch of IT terminologies may look impressive on the outside, yet it does not indicate his/her competence as an engineer who is capable of thinking in terms of systems.

Coming up with a gameplay system which meets every single design request might be an impossible task. However, we can still minimize the necessity of refactoring the whole system if we make sure that it is as versatile as possible in the first place. The goal of engineering is to mitigate the issue of complexity, not necessarily to get rid of it entirely (because such a goal is too idealistic to be achievable).

Therefore, it my belief that beginning a game development project with a highly robust gameplay system is a crucial step to take in order to prevent the occurrence of tech debt as much as possible. And for such a purpose, I have come up with a new model of gameplay systems which I decided to refer to as "Force-Exchange Network".

In a force-exchange network, actors (i.e. gameplay agents) dispatch force vectors to one another, which travel across the network of places (i.e. spatial zones) and eventually reach their recipients. Those recipients, then, apply these force vectors to their state vectors and respond by dispatching their own force vectors.

Some of the key benefits of this design can be outlined as the following:

(1) The componentization of events in the form of vector quantities (e.g. force vectors, result vectors) helps us specify game rules as vector transformation functions (aka "transfer functions") instead of a complicated set of conditional statements.

(2) Since events communicate their effects via a medium (i.e. force-exchange network), it is easy for the system to intervene with the game's cause-and-effect relations and modify them as needed. In a "peace zone", for example, the developer can simply turn off all damage-causing forces by letting the communication network simply dismiss them during the routing process.

I drew inspirations for this model of gameplay from two people.

(1) Peter GärdenforsProfessor Gärdenfors is a cognitive scientist and a philosopher at Lund University (Lund, Sweden), whose two-vector model of causality and the idea of "forces in conceptual space" helped me model gameplay events as instances of vector transformation. Please read Game Design using Gärdenfors' Event Model to learn more about the way his ideas contributed to the computational modeling of events and their causal relations.

(2) Glenn PuchtelGlenn Puchtel is a principal software architect/engineer at GRUBBRR (Boca Raton, Florida), whose ideas in bio-inspired emergent systems (i.e. biocybernetics, wetware, etc) as well as their architectural implications inspired me to construct a network-based topology of the gameplay system. Please read Emergent Systems based on Glenn Puchtel's Biocybernetic Theory to learn more about the way his ideas contributed to the formation of the force-exchange network model.

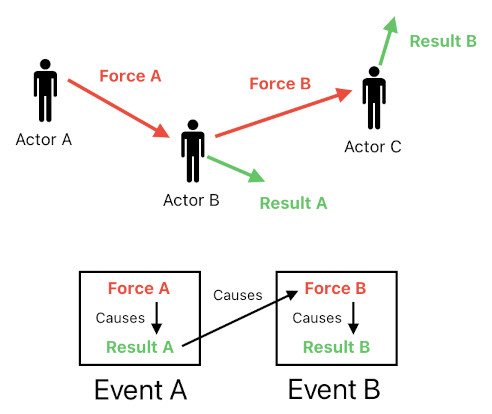

The force-exchange network model of gameplay starts with a core concept called "events". Everything which happens in our game is an event, and events form chains of causality based upon their cause-and-effect relations.

Suppose that there are actors (i.e. gameplay agents) in the game world. Actors experience events, yet these events are causally bound to one another in terms of forces and their results. A force triggers an event, the event applies the force to the actor (thereby generating a result), and the result, in turn, emits a force which triggers yet another event, and so on.

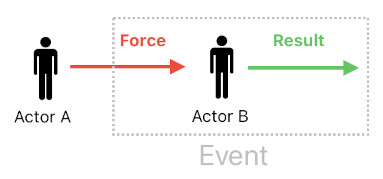

When an actor receives a force from another actor, it applies that force to itself and generates the appropriate result. This force-to-result conversion process, as a whole, is basically what an "event" is. Such a representation of an event can be described as an example of the "two-vector model of causality" in Professor Gärdenfors' theory in cognitive science.

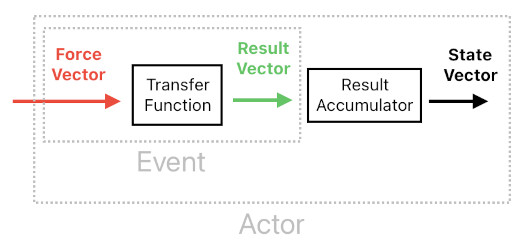

What is really important, though, is the inner workings of the event itself. In Game Design using Gärdenfors' Event Model, I have mentioned that an event can be interpreted as a process of transforming the incoming force vector to its corresponding result vector, as well as that such transformation can be achieved by means of a transfer function (i.e. a list of one-to-one mappings between scalar values).

In addition, what is happening inside an actor as it undergoes an event should also be noted. An actor first receives an incoming force vector, transforms it into the result vector (via the transfer function), and accumulates that result vector in its own persistent vector called "state vector". This special vector represents the current state of the actor, and can be considered the cumulative sum of all the result vectors produced so far.

The following code demonstrates how force vectors, result vectors, and state vectors can be implemented. They are all subtypes of IAbstractVector, which is a generic data type containing a list of numerical values. The "ForceVectorComponentIndex" enum indicates the meaning of each coordinate in a force vector, the "ResultVectorComponentIndex" enum indicates the meaning of each coordinate in a result vector, and so on. In this example, the 4th coordinate of the incoming force vector characterizes the healing/damaging force, which is responsible for influencing the 4th coordinate of the result vector which characterizes the change in the actor's health.

public enum ForceVectorComponentIndex

{

PositionForceX,

PositionForceY,

RadiusForce,

HealthForce,

}

public enum ResultVectorComponentIndex

{

PositionChangeX,

PositionChangeY,

RadiusChange,

HealthChange,

}

public enum StateVectorComponentIndex

{

PositionX,

PositionY,

Radius,

Health,

}

public interface IAbstractVector

{

int[] Components { get; }

}

public class ForceVector : IAbstractVector { ... }

public class ResultVector : IAbstractVector { ... }

public class StateVector : IAbstractVector { ... }And the code below shows how a transfer function can be implemented. Here, "MinForceValue" is the staring value of the x-axis of the transfer function, and "TransferValues" are the list of f(x) values corresponding to the values in the x-axis (if we suppose that f(x) is the mathematical notation denoting a transfer function). "ForceVectorComponentIndex" indicates the type of force the function's x-axis represents, and "ResultVectorComponentIndex" indicates the type of result the function's y-axis represents.

Processing of an event is essentially the same thing as executing the "ApplyForceToState" function of its TransferFunction object.

public class TransferFunction

{

public int[] TransferValues;

public int MinForceValue;

public ForceVectorComponentIndex ForceVectorComponentIndex;

public ResultVectorComponentIndex ResultVectorComponentIndex;

public TransferFunction(...)

{

...

}

public AddModifier(TransferFunction modifier)

{

if (modifier.ForceVectorComponentIndex != ForceVectorComponentIndex)

throw new Exception("Force vector component indices do not match.");

if (modifier.ResultVectorComponentIndex != ResultVectorComponentIndex)

throw new Exception("Result vector component indices do not match.");

int N = TransferValues.Length;

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i)

TransferValues[i] += modifier.TransferValues[i];

}

public RemoveModifier(TransferFunction modifier)

{

if (modifier.ForceVectorComponentIndex != ForceVectorComponentIndex)

throw new Exception("Force vector component indices do not match.");

if (modifier.ResultVectorComponentIndex != ResultVectorComponentIndex)

throw new Exception("Result vector component indices do not match.");

int N = TransferValues.Length;

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i)

TransferValues[i] -= modifier.TransferValues[i];

}

public void ApplyForceToState(ForceVector forceVector, StateVector stateVector)

{

int forceValue = forceVector.Components[ForceVectorComponentIndex];

stateVector.Components[ResultVectorComponentIndex] += TransferValues[forceValue - MinForceValue];

}

}After processing the events and adding their results to the state vector, the actor then runs its own behavioral logic and emits outgoing forces, which will then be received/processed by other actors. The other actors, then, may decide to send their own outgoing forces to the aforementioned actor, and so on. This back-and-forth transmission of forces allows the system to give birth to complex chains of causality, without requiring the architect to configure them manually. Such chains simply "emerge" out of where the actors are located and what the characteristics of their transfer functions are.

There is a reason why my proposed model of gameplay systems is called "Force-Exchange Network". It is because network-oriented communication is the heart of what makes this model work.

When an actor emits a force vector, how shall we make sure that it will be received by the intended recipients? Unless every actor is sending force to everyone else all the time, we must attach some metadata to the force vector for the purpose of guiding it to its proper destination, such as the target location, places it has already visited so far (so as not to visit the same place over and over again), etc.

The following code shows a wrapper class which will works as a "parcel" for delivering force vectors. This class is simply called "Force", and is where the force vector and its metadata are packaged together. This is what an actor actually sends to other actors whenever it "emits a force".

public class Force

{

public HashSet<Place> VisitedPlaces;

public int TargetPositionX;

public int TargetPositionY;

public int TargetRadius;

public ForceVector ForceVector;

}So, we have this thing called "Force" which is analogous to a letter in a mail delivery service. But how to deliver it to its designated location? In order to answer this question, we must first picture the game world as a collection of spatial entities and then proceed to interpret them as nodes in a communication network.

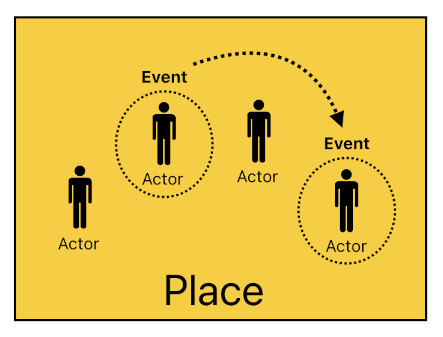

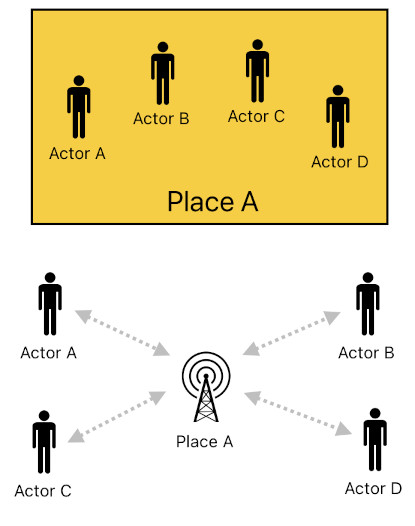

First of all, let us imagine that the game world consists of a number of places, where a "place" is a fixed region in space. Each place contains a number of actors in it, who are responsible for exchanging forces with one another.

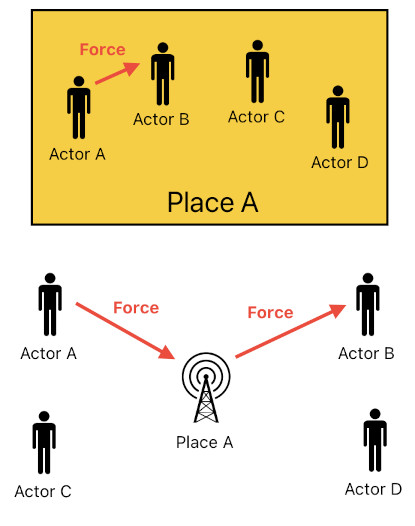

Spatially speaking, a place is an area which encloses its actors. From a communication point of view, though, a place is something more than that. Since an actor communicates with another actor "through space", we ought to imagine a place not as a static region, but as a "force router" which works as a medium of signal transmission (This concept is thoroughly explained in the "Indirect Communication" section of Emergent Systems based on Glenn Puchtel's Biocybernetic Theory).

A place acts as a "cellphone tower" in this respect. It "routes" forces to their rightful recipients, just like a cellphone tower routes voice signals to their receivers' mobile devices. One of the main benefits of this indirect means of communication is that it prevents tight coupling among the actors themselves.

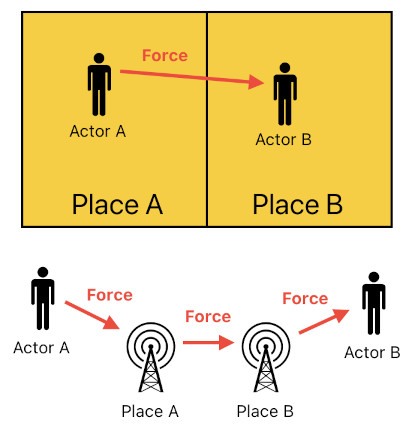

What if the sender and recipient are in two different places? In this case, the sender's place should first route the sender's force to the recipient's place. The recipient's place, then, will route the received to the recipient, thereby completing the line of delivery.

The following snippet shows the code implementation of the "Place" data structure. From a topological point of view, each place is a node in a graph with its own edges to its adjacent places (i.e. "neighboringPlaces") as well as a set of actors it contains. The four numbers, "boundaryX1", "boundaryY1", "boundaryX2", and "boundaryY2", refer to the place's spatial boundaries.

Whenever a place receives a force, its "RouteForce" function gets called. This function compares the force's target region with the spatial regions of the place's constituent actors as well as neighboring places, and routes the force to every one of them whose region intersects that of the target region (because anyone who lies outside of the target region is not supposed to receive the force).

public abstract class Place

{

private HashSet<Actor> actors;

private HashSet<Place> neighboringPlaces;

private int boundaryX1;

private int boundaryY1;

private int boundaryX2;

private int boundaryY2;

public Place(...)

{

...

}

public void RouteForce(Force force)

{

force.VisitedPlaces.Add(this);

ApplyFilter(force);

foreach (Actor actor in actors)

{

actor.ReceiveIncomingForce(force);

}

foreach (Place neighboringPlace in neighboringPlaces)

{

if (!force.VisitedPlaces.Contains(neighboringPlace))

{

int forceX1 = force.TargetPositionX - force.TargetRadius;

int forceY1 = force.TargetPositionY - force.TargetRadius;

int forceX2 = force.TargetPositionX + force.TargetRadius;

int forceY2 = force.TargetPositionY + force.TargetRadius;

if ((forceX1 <= boundaryX2 && forceX2 >= boundaryX1) &&

(forceY1 <= boundaryY2 && forceY2 >= boundaryY1))

{

neighboringPlace.RouteForce(force);

}

}

}

}

public void Update()

{

// Re-evaluate and rearrange actors (based on their current positions).

...

}

private abstract void ApplyFilter(Force force);

}The game world, as a whole, may as well be considered a graph which is made out of "Place" nodes. Such a world is fairly convenient to devise, both manually and procedurally, since each place can be thought of either a room or a hallway of a dungeon, etc. Besides, the center of each place may also serve as a pathfinding node, from which a set of more granular pathfinding nodes can branch out.

One may ask, "Why do we even need a network-based communication scheme for exchanging forces? Can't an actor just look up other actors and send forces directly to them?"

And indeed, it is a feasible option. However, there are reasons why I insist that transmitting forces via a network of routers (i.e. places) is a much better idea from an architectural standpoint than direct actor-to-actor force transmission.

The first reason is that the game may not necessarily be single-threaded, single-player, and completely synchronous. It might be an online game which is supposed to be played across multiple servers, in which case the network-based topology accurately reflects the way in which things ought to be arranged. Each server machine, for instance, may serve as a separate "place" in this game, being an actual router of signals inside a real computer network. And even if the game is single-player, modern computing devices often expect us to leverage their power of multithreading (by means of worker threads, etc). In this case, allocating the jobs of different places (i.e. force routers) to different threads becomes a feasible option as long as these places possess their own asynchronous message queues, etc.

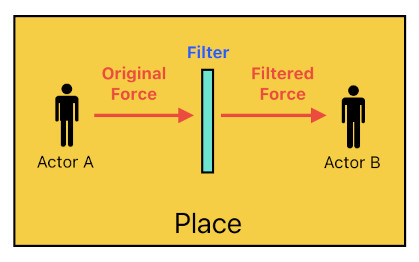

The second reason is that using a place as a medium of force transmission allows us to create places with their own ways of intervening with the forces (aka "force filters"). When designing a video game, we often feel that the system ought to be able to change the manners in which the actors interact with each other based on where they are located (e.g. "The game must disable damage effects if the players are in a peace zone", etc). Force filters easily fulfill this kind of expectation by filtering forces via custom methods before they reach their recipients.

The following code shows how different types of places are able to have their own filters. The "ApplyFilter" method is what applies the place's force filter to any force it happens to be routing. Each subclass of "Place", which represents a custom place type, includes its own definition of "ApplyFilter", allowing it to filter forces in its own way.

public class RegularPlace : Place

{

private void ApplyFilter(Force force)

{

}

}

public class DamageDisabledPlace : Place

{

private void ApplyFilter(Force force)

{

if (force.ForceVector.Components[(int)ForceVectorComponentIndex.HealthForce] < 0)

force.ForceVector.Components[(int)ForceVectorComponentIndex.HealthForce] = 0

}

}

public class MechanicalForceDisabledPlace : Place

{

private void ApplyFilter(Force force)

{

force.ForceVector.Components[(int)ForceVectorComponentIndex.PositionForceX] = 0;

force.ForceVector.Components[(int)ForceVectorComponentIndex.PositionForceY] = 0;

}

}"RegularPlace" is a place which does not intercept forces at all; it simply lets forces pass through the vacuum. "DamageDisabledPlace" is some kind of "peace zone" where none of the actors are able to hurt each other (because all negative (damaging) health forces are clamped to 0). "MechanicalForceDisabledPlace" is a chunk of space in which all mechanical interactions are disabled (e.g. collision, knockback, etc), which means that all actors can simply pass through one another like ghosts.

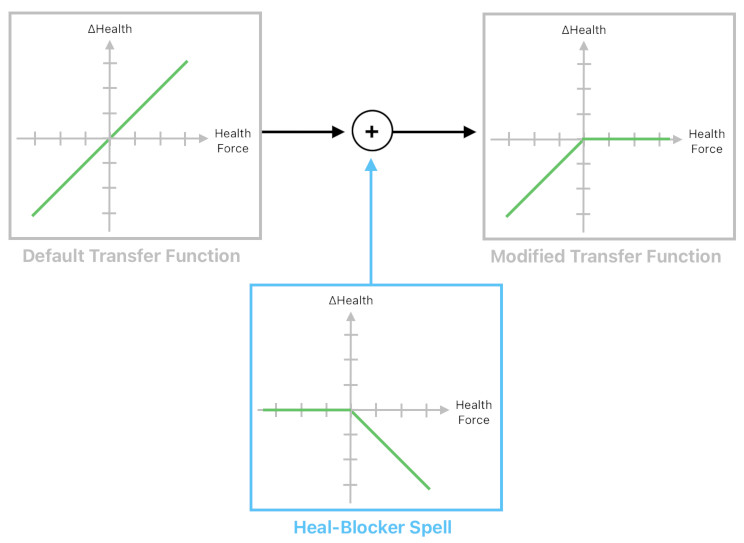

In Game Design using Gärdenfors' Event Model, I have mentioned that an actor's status condition (e.g. spell, upgrade, etc) can be implemented as a modification to the event's transfer function. The simplest approach is to model each status condition as a function which temporarily gets added to the event's original transfer function, thereby "warping" the way in which the event transforms the incoming force vector.

The question of when to add or remove a status condition, though, presents us with a major technical challenge. A brute-force implementation is to just let actors identify each other and directly invoke each other's "AddStatusCondition(...)" or "RemoveStatusCondition(...)" methods, and so forth, but such a direct solution violates the architectural elegance of the network-based communication protocol.

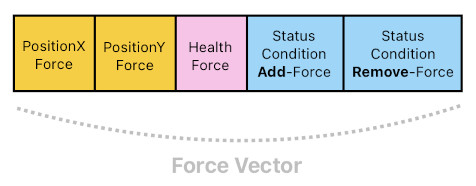

A significantly better solution is to let the addition and removal of a status condition be part of a force vector. This allows each actor to apply a status condition to another actor by sending a force vector, instead of relying on other means. The image below shows an example layout of a force vector which supports status conditions. The "Add-force" component refers to the number of times the corresponding status condition should be added to the recipient actor, and the "Remove-force" component refers to the number of times the corresponding status condition should be removed from the recipient actor.

And here is the augmented version of the "ForceVectorComponentIndex" enum. As you can see from the code below, each separate type of status condition has its own pair of force vector components - AddForce and RemoveForce.

public enum ForceVectorComponentIndex

{

PositionForceX,

PositionForceY,

RadiusForce,

HealthForce,

StatusConditionAddForce_HealBlocker,

StatusConditionRemoveForce_HealBlocker,

StatusConditionAddForce_Stun,

StatusConditionRemoveForce_Stun,

StatusConditionAddForce_Poison,

StatusConditionRemoveForce_Poison,

StatusConditionAddForce_Freeze,

StatusConditionRemoveForce_Freeze,

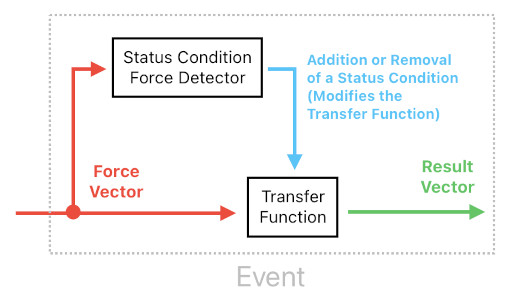

}A little bit of change in the event-processing logic will be required to make this design work. Previously, we were merely assuming that the event takes the incoming force vector, plugs it into the transfer function, and computes the corresponding result vector. When status conditions are involved, however, the incoming force vector's components which are related to status conditions must be identified/processed via a different procedure. Instead of going through the transfer function, these components will turn themselves into "modifier functions" which will then be added to (or subtracted from) the transfer function.

The code below is how a status condition should be implemented. Each status condition consists of two parts - is modifier function and expiration time. The modifier function is structurally the same as a transfer function (hence the reason why its type is "TransferFunction"), except that its role is to modify an existing transfer function instead of serving as one. The expiration time is for cases in which the status condition is supposed to be automatically removed from the actor after a certain duration of time, without requiring it to be removed explicitly. The "StatusConditionFactory" class is basically a lookup table for each status condition type's modifier function and lifespan.

public class StatusCondition

{

public TransferFunction Modifier;

public float ExpirationTime;

}

public static class StatusConditionFactory

{

public static Dictionary<ForceVectorComponentIndex, () => StatusCondition> GenerationMethods = {

{ForceVectorComponentIndex.StatusConditionAddForce_HealBlocker,

() => new StatusCondition(...)},

{ForceVectorComponentIndex.StatusConditionRemoveForce_HealBlocker,

() => new StatusCondition(...)},

{ForceVectorComponentIndex.StatusConditionAddForce_Stun,

() => new StatusCondition(...)},

{ForceVectorComponentIndex.StatusConditionRemoveForce_Stun,

() => new StatusCondition(...)},

{ForceVectorComponentIndex.StatusConditionAddForce_Poison,

() => new StatusCondition(...)},

{ForceVectorComponentIndex.StatusConditionRemoveForce_Poison,

() => new StatusCondition(...)},

{ForceVectorComponentIndex.StatusConditionAddForce_Freeze,

() => new StatusCondition(...)},

{ForceVectorComponentIndex.StatusConditionRemoveForce_Freeze,

() => new StatusCondition(...)},

};

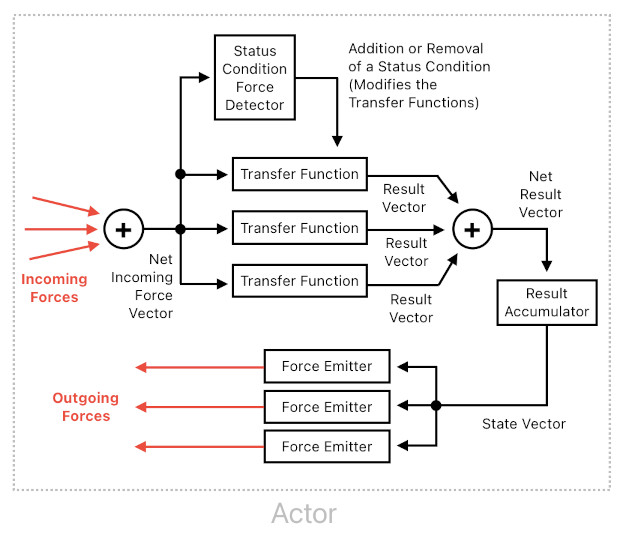

}The diagram below illustrates the overall structure of an actor (i.e. gameplay agent). First, it receives all the incoming forces and adds them together, yielding the net incoming force vector. This single vector contains the composite effect of all the incoming forces which the actor happened to receive at that particular moment in time.

This net vector, then, undergoes two different processes. First, some of its components which are related to the addition/removal of status conditions will trigger the system to add/subtract the appropriate "modifier functions" to/from the transfer functions whose dimension types match, as well as setting timers to handle their expiration. Secondly, the rest of the vector components will be applied to the (possibly modified) transfer functions, yield their corresponding result vectors.

The individual result vectors, then, will eventually be added to the actor's state vector (because, after all, result vectors represent changes in the state vector; they are the differentials). The state vector is the current state of the actor, which means that its components reflect the actor's current x position, current y position, current size in radius, current health, etc. The only "state" outside of this vector is the set of ongoing status conditions that the actor has in itself.

Based on the latest state vector, the actor's "force emitters" then execute themselves and generate the outgoing forces. They can be pretty much any sorts of behavioral commands, such as: "Attack every enemy in range", "Heal the closest friend in front of you", "Apply the slow-down status condition to every enemy in front of you", "Turn yourself toward the closest enemy", and so on.

Note that it is definitely possible to generate an outgoing force whose recipient is the sender itself. This kind of force comes in handy when the actor wants to move or rotate itself (or apply a status condition to itself).

The following code is how an actor can be implemented as a class. Whenever it updates, it processes the incoming force vectors, applies them to the state vector, emits outgoing force vectors, and gets rid of expired status conditions.

public class Actor

{

private Place place;

private ForceVector netIncomingForceVectorPending;

private StateVector stateVector;

private HashSet<TransferFunction> transferFunctions;

private HashSet<ForceEmitter> forceEmitters;

private HashSet<StatusCondition> statusConditions;

private List<StatusCondition> removePendingStatusConditions;

public int PositionX => stateVector.Components[(int)StateVectorComponentIndex.PositionX];

public int PositionY => stateVector.Components[(int)StateVectorComponentIndex.PositionY];

public int Radius => stateVector.Components[(int)StateVectorComponentIndex.Radius];

public Actor(...)

{

...

}

public void ReceiveIncomingForce(Force incomingForce)

{

int dx = incomingForce.TargetPositionX - PositionX;

int dy = incomingForce.TargetPositionY - PositionY;

int thresDist = incomingForce.TargetRadius + Radius;

// Receive the incoming force only if the actor intersects the target region.

if (dx*dx + dy*dy <= thresDist*thresDist)

{

netIncomingForceVectorPending += incomingForce.ForceVector;

}

}

public void SendOutgoingForce(Force outgoingForce)

{

place.RouteForce(outgoingForce);

}

public void Update()

{

foreach (TransferFunction transferFunction in transferFunctions)

{

int N = netIncomingForceVectorPending.Components.Length;

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i)

{

if (StatusConditionFactory.GenerationMethods.TryGetValue((ForceVectorComponentIndex)i, out var method))

{

int numStatusConditionsToAdd = netIncomingForceVectorPending.Components[i];

for (int j = 0; j < numStatusConditionsToAdd; ++j)

{

AddStatusCondition(method());

}

}

}

transferFunction.ApplyForceToState(netIncomingForceVectorPending, stateVector);

}

foreach (ForceEmitter forceEmitter in forceEmitters)

{

Force outgoingForce = forceEmitter.GenerateOutgoingForce(actor, stateVector);

SendOutgoingForce(outgoingForce);

}

for (int i = 0; i < netIncomingForceVectorPending.Components.Length; ++i)

{

netIncomingForceVectorPending.Components[i] = 0;

}

foreach (StatusCondition statusCondition in statusConditions)

{

if (statusCondition.ExpirationTime > Time.time)

removePendingStatusConditions.Add(statusCondition);

}

foreach (StatusCondition removePendingStatusCondition in removePendingStatusConditions)

{

RemoveStatusCondition(removePendingStatusCondition);

}

removePendingStatusConditions.Clear();

}

private void AddStatusCondition(StatusCondition statusCondition)

{

statusConditions.Add(statusCondition);

foreach (TransferFunction transferFunction in transferFunctions)

{

if ((transferFunction.ForceVectorComponentIndex == statusCondition.TransferFunction.ForceVectorComponentIndex) &&

(transferFunction.ResultVectorComponentIndex == statusCondition.TransferFunction.ResultVectorComponentIndex))

{

transferFunction.AddModifier(statusCondition.Modifier);

}

}

}

private void RemoveStatusCondition(StatusCondition statusCondition)

{

statusConditions.Remove(statusCondition);

foreach (TransferFunction transferFunction in transferFunctions)

{

if ((transferFunction.ForceVectorComponentIndex == statusCondition.TransferFunction.ForceVectorComponentIndex) &&

(transferFunction.ResultVectorComponentIndex == statusCondition.TransferFunction.ResultVectorComponentIndex))

{

transferFunction.RemoveModifier(statusCondition.Modifier);

}

}

}

}

public class ForceEmitter

{

public Force GenerateOutgoingForce(Actor actor, StateVector stateVector)

{

...

}

}The schematics and code shown so far, of course, do not cover the full picture of the force-exchange network system. There are many more things which ought to be added to make it usable for gameplay purposes. Here are some of the future implementations which I think may be necessary:

(1) Force with delay (e.g. projectile)In many cases, forces are not instantaneous; they need time to propagate. Therefore, it may be desirable to attach an additional "delay" attribute to the Force object, telling the Place objects that they must wait for a certain duration of time before routing it to either the recipient or another place.

(2) Function-based force emission logicI have not demonstrated any logic for generating outgoing forces. Technically speaking, it is not impossible for an actor to simply look up other actors (via references to its current place, neighboring places, etc), go through a custom logic (with a bunch of hard-coded conditional/iterative statements), and decide what forces to emit. Although such an approach is straightforward, it is far more prone to error and complexity than the way in which incoming forces are being processed. Thus, we will probably need an outgoing-force equivalent of the "transfer function".

(3) Place with its own force-emitting behaviorsJust like actors are capable of emitting forces, places may need to be able to emit forces as well. A sauna, for example, is a place which constantly emits "heat force" to all the actors in it. Also, this kind of logic lets us devise places with their own "force fields" (e.g. gravity), as opposed to places which act like complete vaccum in outer space.

(4) Observation by means of "notification forces"While it is definitely possible to let actors directly perceive each other's presence based on references (i.e. reference to the current place + reference to neighboring places + reference to each place's constituent actors, etc), such direct dependency is not so desirable from an architectural point of view. Also, it makes it hard to implement visibility-warping gameplay features such as stealth-mode, and so on. Thus, it may be better to let each actor emit not only state-changing forces such as "knockback", "heal", "damage", etc, but also "notification forces" which notify the actor's presence. This lets the process of observing other actors be passive (i.e. You just wait to receive notification forces instead of actively searching for other actors on your own).

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service