Author: Youngjin Kang Date: June 28, 2024 - July 27, 2024

This is a collection of mathematical concepts designed to express the nature of human mind in a rational manner.

The ideas shown below are inspired by Katarina Gyllenbäck's articles. For more information, visit Here.

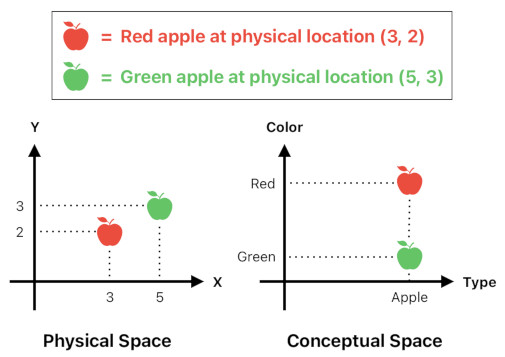

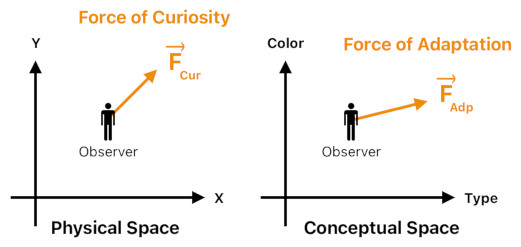

There are two different spaces in our universe - physical space and conceptual space.

Physical space is the space we usually refer to whenever we are employing the word "space". It consists of spatial and temporal axes (e.g. X, Y, Z, and Time), and serves as a frame of reference when it comes to describing physical entities such as rigid bodies.

Conceptual space, on the other hand, is the space of qualitative features. For example, a color is a position in the RGB color space, where the axes (R, G, B) represent the intensity levels of the three primary color components (i.e. Red, Green, Blue). The RGB color space is one of many types of conceptual spaces we can imagine.

Each object has its own position in physical space as well as a position in conceptual space. The former tells us where the object is, and the latter tells us what the object looks like.

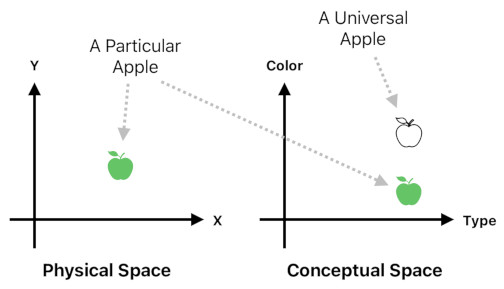

There are two types of objects - particulars and universals.

A particular is an object which exists at a specific point in space and time. All tangible objects, such as a table we can touch, a sandwich we can eat, a cup we can hold, and countless other "real" things, can be classified as particulars.

A universal is different from a particular in the sense that we cannot directly perceive it, since it exists only in conceptual space and not in physical space. It is a pure idea which resides only in the spiritual realm; it does not belong to anywhere in our material world.

In computer science, a class is a universal. It is purely spiritual because it lives in the static memory, which is fixed and therefore "eternal" in the sense that it spans the entirety of the application's runtime.

An instance of a class, which is dynamically allocated in memory, is a particular. It is a mortal being which gets created at some point in time and gets destroyed at some other point in time. It is never eternal because it does not span the entirety of the application's runtime.

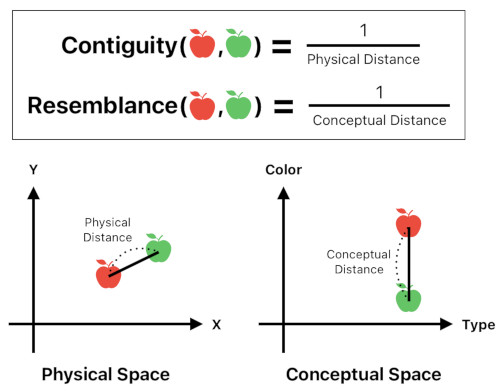

Since an object exists in two different spaces (namely, "physical space" and "conceptual space"), a distance between a pair of objects can possess either one of two meanings depending on the type of space in which it is measured.

Physical proximity implies contiguity. When two things are very close to each other in physical space, we say that they are contiguous because looking at one of them lets us look at the other much more easily.

Conceptual proximity implies resemblance. When two things are very close to each other in conceptual space, we say that they resemble each other because thinking of one of them lets us think of the other much more easily.

Proximity can be measured by taking the reciprocal of the distance. Less distance means more proximity, and more distance means less proximity.

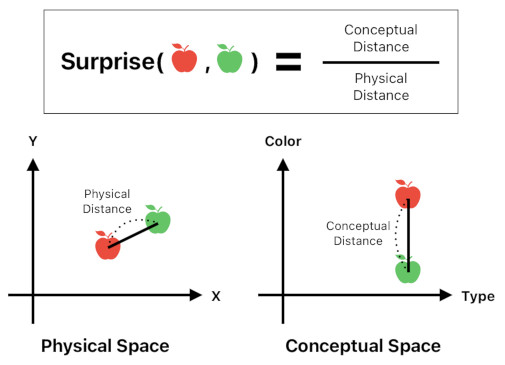

How to measure the amount of surprise between two objects?

Each object has two distinct positions - one in physical space, and the other one in conceptual space. Therefore, we are able to compute two separate distances between a pair of objects - physical distance and conceptual distance.

The amount of surprise between two objects is proportional to their conceptual distance because the more qualitatively different they are, the more surprised they will be when they see each other.

On the other hand, the amount of surprise between two objects is inversely proportional to their physical distance because the closer they are, the more vividly they will observe each other's qualitative differences.

Thus, we can measure the amount of surprise by measuring the conceptual distance and then dividing it by the physical distance.

Curiosity often drives us to move from familiar places to unfamiliar places. It is possible to devise a mathematical formula which tells us exactly how the force of curiosity will initiate such a movement.

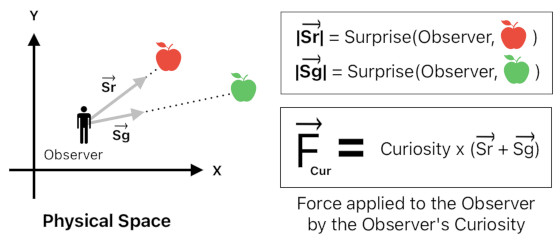

Suppose that there is an observer somewhere in physical space. We can first compute the observer's "surprise vectors", each of which represents the amount of surprise that the observer feels in regard to an external object.

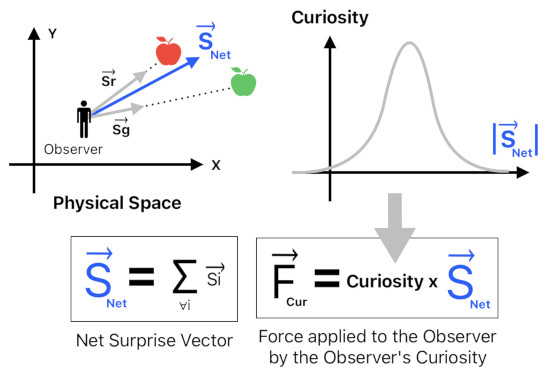

If you take the sum of all the surprise vectors which involve the observer and multiply the resulting "net surprise vector" by the amount of the observer's curiosity, you will obtain the "curiosity force vector" which is responsible for pushing the observer to venture into the unknown.

Can we represent curiosity as a numerical quantity?

The amount of curiosity reaches its peak value when the person is feeling a sense of surprise which is neither too intense nor too dim.

If you are surrounded by an environment which is not surprising at all, you will lose curiosity due to boredom.

If you are surrounded by an environment which is too overwhelmingly surprising, you will be anxious. As a result, you will suppress your curiosity in order to protect yourself from potential dangers.

It is only when you are surrounded by a moderately surprising environment (i.e. neither too familiar nor too unfamiliar) that you will be able to feel a vivid sense of curiosity.

A halfway mixture between familiar and unfamiliar elements creates a "Goldilocks zone of motivation" which will encourage you to uncover partially hidden secrets.

If everything is already uncovered, there will be no secret to uncover and so you won't feel the necessity to start an adventure. If everything is veiled in darkness, you will feel clueless and thus not even dare to start an adventure.

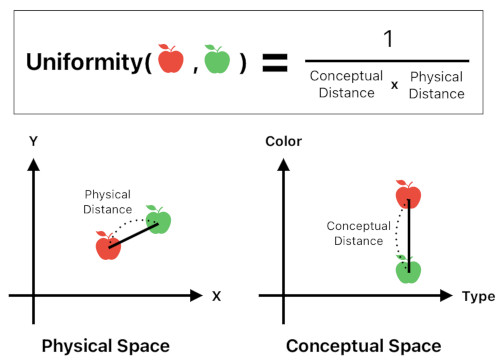

It is possible to measure the amount of uniformity between two objects.

In order for a pair of objects to comprise one uniform body, they must satisfy two conditions.

First, they must be physically close to each other. If they are too far apart, we will clearly be able to see that there is a significant spatial gap between them, showing that they are discontinuous and thus not uniform.

Secondly, they must resemble each other (i.e. similar in characteristics). If they look too drastically different, we will be able to tell that their mutual contrast is too huge to ensure that they are part of one smooth, uniform body.

Therefore, the amount of uniformity can be computed by taking the inverse of the product between their physical and conceptual distances.

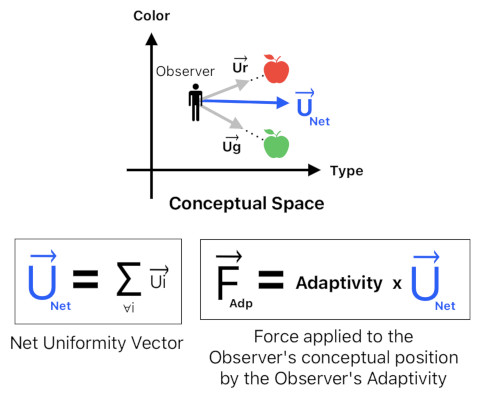

If you measure the amount of uniformity between the observer and a nearby object, you will obtain a number which tells you how familiar the observer is with the object.

And if you represent this number as the magnitude of a vector which starts at the observer's conceptual location and points itself to the object's conceptual location, you will get a vector which can be referred to as a "uniformity vector".

Take the sum of all uniformity vectors which originate from the observer, and you will acquire the net uniformity vector. This vector informs us the strength and direction of the surrounding environment's familiarity with respect to the observer.

Scale this net uniformity vector by the observer's adaptivity (which is a scalar value) and you will obtain the force vector which is currently pushing the observer's viewpoint in conceptual space. This force gradually "adapts" the observer to the surroundings, making them become more and more familiar as time passes by.

The force of curiosity pushes the observer's body in physical space, toward areas which are unfamiliar to him.

Meanwhile, the force of adaptation pushes the observer's viewpoint in conceptual space, toward areas which are as familiar to him as possible. This lets him quickly adapt himself to his surroundings.

These two forces work together in parallel, continuously propelling both the observer's body (location in physical space) and viewpoint (location in conceptual space) in the direction of spontaneous exploration.

The back-and-forth interaction between these two forces creates a feedback system. The force of curiosity puts the observer in unfamiliar places, which in turn compels the observer to adapt his viewpoint to the unfamiliar. Once his surroundings become too familiar to him, his curiosity then drives him to search for other unfamiliar territories to explore.

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service