Author: Youngjin Kang Date: June 14, 2024

Let me introduce a series of articles on Narrative Construction, written by Katarina Gyllenbäck.

Katarina Gyllenbäck is a narrative game designer with an academic background in both Drama & Theatre Arts and Computer Science. She invented a brand new method of narrative design called "Narrative Bridging", and has conducted numerous interdisciplinary researches in the field of interactive media (including video games).

She used to be a director and scriptwriter for the motion picture industry, but then she is also well-known as a researcher at SICS (Swedish Institute of Computer Science) and other academic institutions, as well as a co-founder of CIN (Creating Interactive Narrative). She is also a lifelong educator who tutors, lectures, and writes on topics which pertain to both the science of narratives, the science of computation, and their domain of interplay (i.e. science of cognition).

Outside of academia, she worked as a design director & narrative designer of video games at a number of software development studios, including Bambino Games and Softbox AB.

This is a very concise and easy explanation of what a narrative is. This will give you a nice overview of what the author intends to communicate through her articles.

This is the backstory of what inspired the author to develop her own method of narrative design called "Narrative Bridging". As alluded Here, for instance, Narrative Bridging primarily aims to bridge the gap between narratives (i.e. things which writers/designers focus on) and mechanics (i.e. things which programmers/engineers focus on), by means of iteration between the bottom-up (i.e. "mechanics-to-narratives") and top-down (i.e. "narratives-to-mechanics") design processes. In the former case, developers start by creating a set of basic building blocks of interaction, and then build layers of abstraction on top of them to give birth to a body of dynamic storytelling. In the latter case, developers start by devising the overall body of narratives (e.g. storyline, theme, etc), and then add systematic elements to it to give life to the story.

It has traditionally been claimed that "showing" is better than "telling" when it comes to communicating one's thoughts. This article, however, explains why even "showing" is not enough when we are delivering our narratives through an interactive medium instead of a one-way medium (such as a book or a film, in which the viewer's choice of action does not influence the story's progress). The author says that a dynamic (interactive) narrative should neither "tell" nor "show" the story, but instead "involve" the viewer by motivating him/her to make meaningful choices. The author further expounds that such a motivation can be triggered by introducing a conflict between two opposing forces (i.e. duality), and that one's recognition of such a conflict should be made possible by exploring the world and discovering its dual properties.

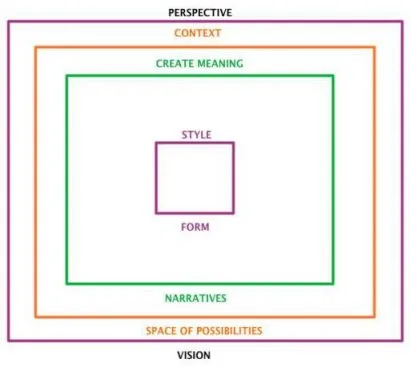

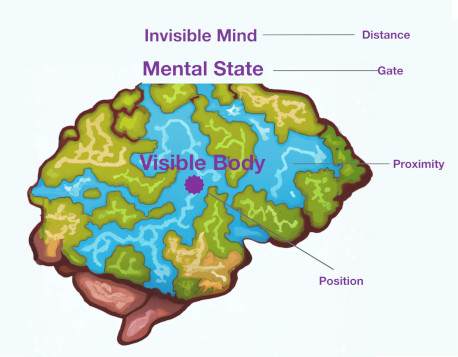

This article explains how a narrative can be modeled inside a "conceptual space" (i.e. a hypothetical geometry in which narrative elements are being placed as spatial objects). The underlying motivation behind this space-oriented approach is that each spatial axis (dimension) essentially represents a duality between two opposing forces (e.g. Good and Evil, Life and Death, Visible and Invisible, etc), so that, if we construct an N-dimensional conceptual space, we will be able to define every single narrative element as a combination of N dualistic attributes. Also, the center of the conceptual space may be considered the observer's position, and we may suppose that points close to the observer are things that are familiar, while points far away from the observer are things that are unfamiliar. The author explains that the space may as well be "warped" by the way in which narrative elements are placed (in the form of obstacles, shortcuts, etc), which will then drive the audience (observer) to either move from the familiar to the unfamiliar, or from the unfamiliar to the familiar (The former case could be described as "a moment of surprise", and the latter case could be described as "a moment of relief").

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service