Author: Youngjin Kang Date: September 22, 2025

This article is Part 13 of the series, "Linear Algebra for Game Development". If you haven't, please read Part 1 first.

At this point, you may have noticed that something vital has been missing. And you probably guessed it right.

A game has a set of rules. When we are playing a game, we expect everyone to follow these rules. A more precise way of saying this is that there are conditions which must not be violated, and that there are events which are not allowed to happen if they do not satisfy these conditions.

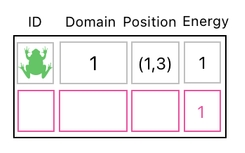

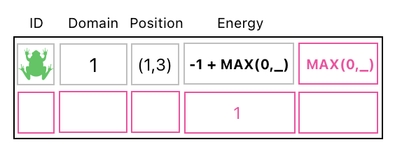

Suppose that one of the rules in our game is that "energy" can never be a negative number. So, for example, if a frog's current energy level is 1 (as shown below):

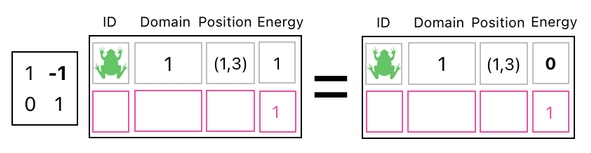

It will be okay for us to subtract 1 from it, since the resulting value (0) is still a nonnegative number. This is all good, everyone is happy, and no rule has been violated so far.

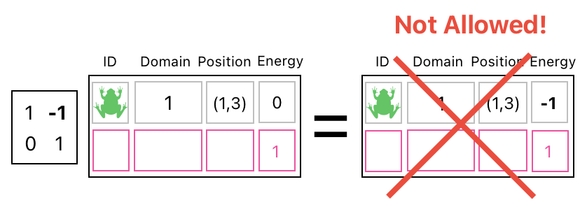

But if we are to decrement the energy level by 1 once again, we will be in trouble. It is because turning the energy level from 0 to -1 is not allowed. It does not make sense for a frog to store a negative amount of energy in its body.

And here is where a major technical difficulty arises. In the language of matrix multiplication, a rule such as "Energy cannot be a negative number" is not really enforceable.

When we multiply our table by a matrix, all it does is simply apply the same arithmetic operation to every one of its numbers; there is no way for it to block some of the entries from being modified if their results are deemed nonsensical.

How, then, shall we overcome this obstacle? The problem is that linear algebra, by definition, does not fair well with conditionals.

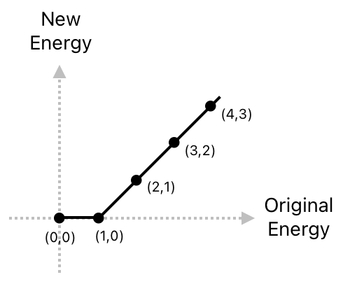

Whenever we select one of multiple potential outcomes based upon a condition, we inevitably introduce an "abrupt edge" in the landscape of the system's input/output pattern which would have otherwise been a nice straight line. Take a look at the graph below, for instance.

This is a graphical illustration of the relationship between each energy value and its expected result when we attempt to decrement it by 1. As you can see, the numerical relation between these two stays linear (i.e. falls upon a straight line) as long as the original energy is a positive number. The moment we try to decrement energy which is already 0, however, a sudden change in direction occurs. This is where linearity breaks down.

And, as you may know, linear algebra is called "linear" because it primarily deals with things that are linear (straight) in nature, rather than those involving edges and curves.

How to circumvent this problem, then?

One potential solution is to try to "linearize" our nonlinear system by introducing variables whose linear combinations can somehow be interpreted as models of nonlinear phenomena (e.g. system of equations for an N-th polynomial), and so forth, but this kind of approach is way too abstract and is prone to confuse people who are not well versed in mathematics.

An easier alternative is to stop trying to use linear algebra for every single problem, and casually let us fall back to solutions which are not solely made up of matrix multiplications.

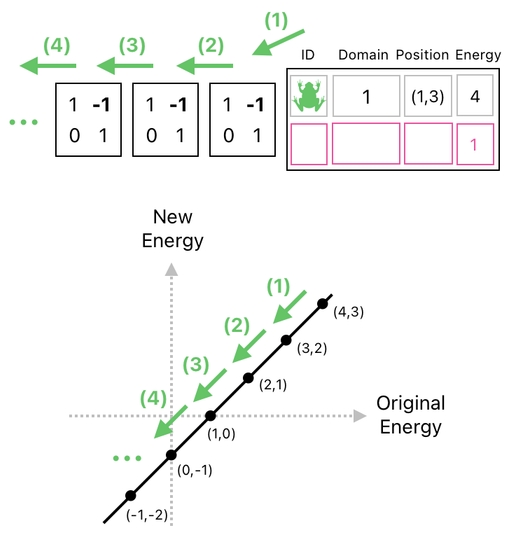

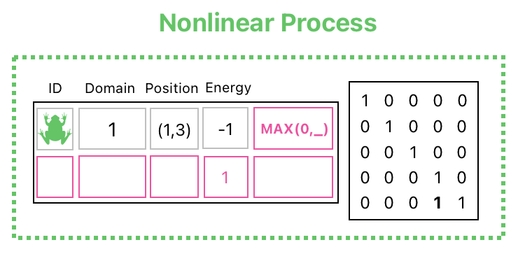

First of all, we all know that if we just keep repeatedly multiplying our data table by the same matrix which is responsible for reducing the frog's energy level by 1, we will soon see our frog's energy becoming a negative number (as shown below).

It is because a strictly linear operation (such as a matrix operation) exhibits the same behavior everywhere on the number line. It does not care whether the frog's resulting energy level makes sense or not; it simply subtracts 1 from the existing number unconditionally.

In order to implement conditional behaviors, therefore, we need something other than just matrix multiplications, which is what I would like to call a "filter".

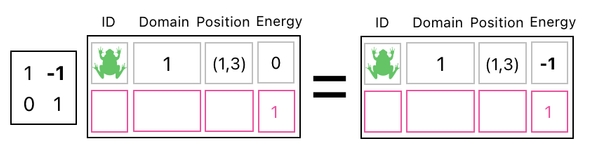

Here is an idea. Why don't we just drop the frog's energy by 1 for now, without judging whether the resulting number will make sense or not?

Immediately after doing so, we can then proceed to "clean up" any bit of the ensuing nonsense from our system.

For example, the above picture tells us that we turned the frog's energy level into a negative number (-1) because we decreased it even though it was already 0. This is obviously a nonsense, but it is a kind of nonsense which can be corrected afterwards.

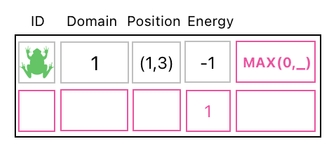

Let us, for instance, attach an extra column to our data table whose topmost element may look a bit unfamiliar to you.

Instead of a number, here is an invocation of a function called "MAX". The role of this function is to compute the maximum of the two values it happens to receive as its parameters, which are respectively denoted by "0" and "_" in our case. The underbar (_) refers to a blank which will be filled later on.

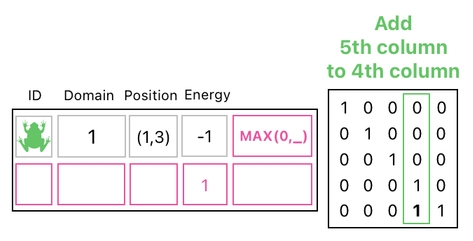

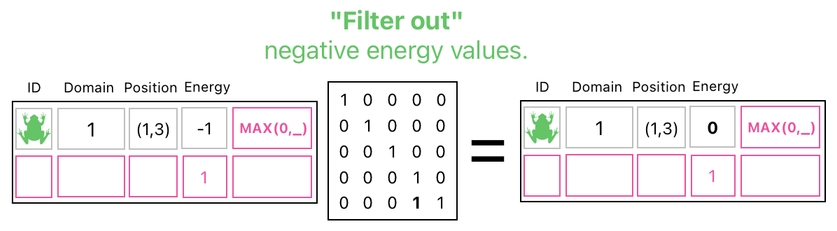

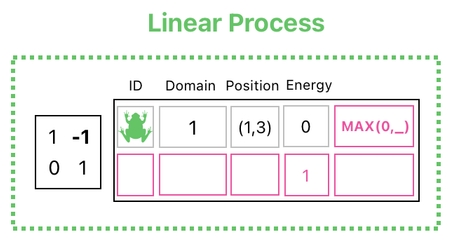

The next step is to multiply our table by a matrix (on the right hand side) which performs the task of adding this extra column to the "energy" column.

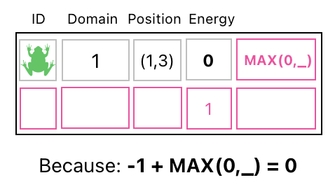

And the result of this? Oh, of course, since we just added "MAX(0,_)" to the frog's nonsensical energy value (-1), the outcome is going to look like what is displayed below.

Let me explain the meaning of this bizarre formula which was produced by our matrix multiplication.

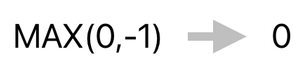

First of all, please excuse me for making up a rule which I guess is not part of "real mathematics". The rule is to assume that, if you "add" a function which contains a blank argument (i.e. "_"), we can move the preceding term (which is "-1" in our case) into the function and let it replace the blank.

If we just let this happen, the rest will be straightforward. I ask you, what is the value of "MAX(0,-1)", which is what we get when we replace the blank with our -1? The answer is that it is 0, since the maximum value between 0 and -1 is 0.

And since "-1 + MAX(0,_)" is equal to "0" according to our rule, it can be asserted that the result of the aforementioned matrix multiplication is the transformation of any negative energy value to 0.

The matrix we just multiplied on the right side of the table to accomplish this job can be called a "filter", mainly because its role is to filter out negative values from the table's "energy" column by zeroing them out.

This is just one of many possible examples. There can be countless other types of filters, which we may leverage for the purpose of solving a variety of problems involving conditions and their appropriate responses.

To be fair, what I have just shown is not really part of linear algebra, since what the "MAX" function does is not even linear in nature. Thus, we should consider the aforementioned filtering step not as a legitimate type of computation in linear algebra, but instead as a nonlinear process.

This, of course, is different from any of the previous operations we had seen before, since they all involved plain numbers (no nonlinear functions) and were therefore guaranteed to be linear.

Reducing the frog's energy by 1, for instance, is a linear process because it only multiplies and adds a bunch of numbers; it never does anything weird such as taking the maximum of two given numbers, etc.

Previous Page

Next Page

Previous Page

Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service