Author: Youngjin Kang Date: January 19, 2025

What makes a good sandwich?

This is perhaps one of the most important questions which have ever been asked in the field of culinary arts. Even the most experienced gastronomers, who have spent their entire lifetime exploring the nature of sandwiches in their extraterrestrial kitchens, struggle to answer it with a sufficient degree of confidence.

No one, however, would deny that composition plays a central role in the making of a high-quality sandwich.

A sandwich comes into existence the very moment we compose its ingredients in the form of a stack. We pile a number of things from bottom to top, and if the order and types of these things are appropriate, we will be able to define the resulting stack as a "sandwich".

And the secret of designing a great sandwich belongs to the way in which the individual elements of the stack are being chosen.

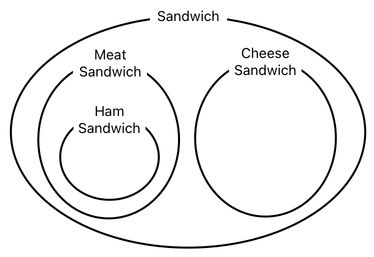

In order to understand what are good sandwiches (as opposed to bad sandwiches), we must first clarify the ways in which they can be categorized. As you have seen in the last article, a taxonomy (i.e. family tree) of sandwiches comes in handy whenever we are attempting to classify them in a hierarchical order.

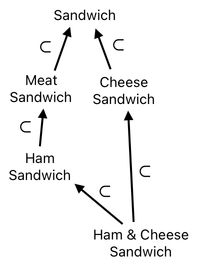

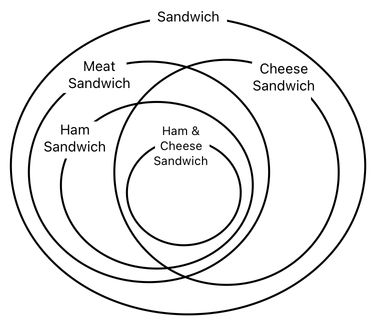

In many cases, however, a strictly hierarchical (i.e. tree-based) organization of categories does not really work. And the reason behind this is that it is perfectly feasible to contrive a sandwich by "mixing" different types of sandwiches.

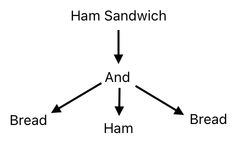

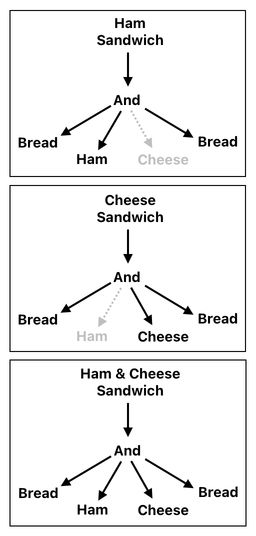

Let me show you an example. The image below is the definition of a ham sandwich.

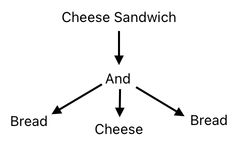

Similarly, the image below is the definition of a cheese sandwich.

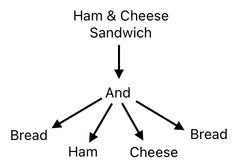

Here is where things start to get interesting. What if I want to put both a slice of ham AND a slice of cheese together, and make a sandwich out of them? In that case, we will have to refer to it as a "ham & cheese sandwich". Its definition is shown below.

This graph is self-explanatory, isn't it? It is called a "ham & cheese sandwich" because it contains both ham and cheese in it.

Here is a problem, though. At which point in the hierarchy should I place this sandwich? Will it be within a subcategory of ham sandwiches (because it is a more specific variant of a ham sandwich), or will it be within a subcategory of cheese sandwiches (because it is a more specific variant of a cheese sandwich)?

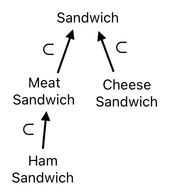

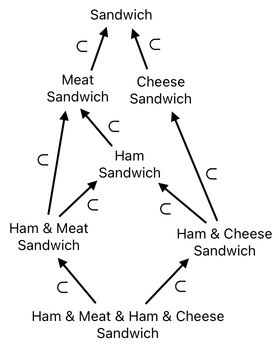

Let us revisit the family tree of sandwiches to find the answer. The diagram below shows the taxonomical relationships among different types of sandwiches.

What is illustrated here is pretty straightforward. "Meat sandwich" is a subset of "sandwich" because the former is more specific than the latter, and "ham sandwich" is a subset of "meat sandwich" because the former is more specific than the latter, and so forth.

What about "ham & cheese sandwich"? First of all, let me just ask a couple of questions.

Is "ham & cheese sandwich" also a "ham sandwich"? Oh, yes. Absolutely! It has ham in it, so it is a ham sandwich. Just because it has cheese in it does not make it a non-ham sandwich. Therefore, "ham & cheese sandwich" is a subset of "ham sandwich".

Here is another question. Is "ham & cheese sandwich" also a "cheese sandwich"? Yes! It has cheese in it, so it is a cheese sandwich. Just because it has ham in it does not make it a non-cheese sandwich. Therefore, "ham & cheese sandwich" is a subset of "cheese sandwich" as well.

So, there we have it. The graph can no longer be called a "family tree" (because it is not a tree anymore), and it is no longer purely hierarchical. Nevertheless, we are able to tell that this sort of representation does accurately reflect the nature of mix-and-match among different sandwich types.

From a set theory point of view, one can say that "ham & cheese sandwich" belongs to the intersection between "ham sandwich" and "cheese sandwich". The reason is that it is both a ham sandwich AND a cheese sandwich at the same time.

Here is a slightly different way of looking at the same subject. A "ham sandwich" only has ham in it, and a "cheese sandwich" only has cheese in it. If you put these two ingredients together inside the same sandwich (by putting them under the same "AND" relation), you will get a "ham & cheese sandwich".

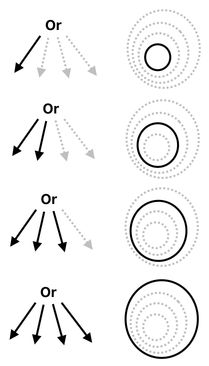

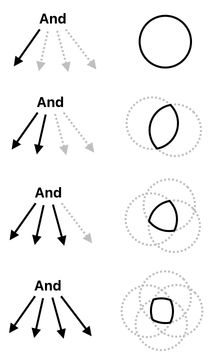

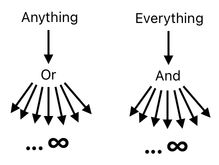

The pattern we are seeing here curiously resembles the "OR" pattern we saw in the last article. Previously, I have demonstrated that the more choices of ingredient a sandwich has, the more general (i.e. broader) it gets when it comes to categorizing it in a hierarchy.

The "AND" equivalent of this phenomenon can be depicted in a similar fashion. Here, combining more and more ingredients in one place will put the sandwich into a denser and denser intersection of sandwich types.

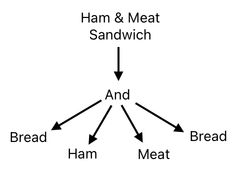

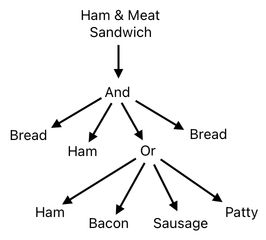

The mix-and-match sort of combination can happen across multiple layers of abstraction as well. For example, nothing prohibits us from stacking "any type of meat" upon a slice of ham, putting this semi-generic pair of ingredients between a pair of bread pieces, and referring to the whole thing as a "ham & meat sandwich".

This, of course, contains its own expandable bundle of details because the word "meat" suggests a multitude of choices.

What is interesting is that we are able to compose things that are already results of their own compositions.

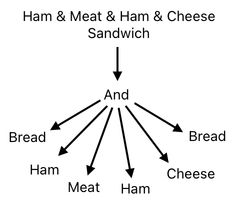

Suppose that I decided to put the ingredients of a "ham & cheese sandwich" on top of the ingredients of a "ham & meat sandwich". The resulting product, then, will be called a "ham & meat & ham & cheese sandwich" (or "HMHC sandwich" for short).

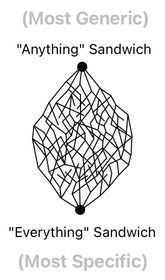

If we graphically depict the hierarchical relationships among the sandwich types introduced so far, we will obtain a diagram which looks like this:

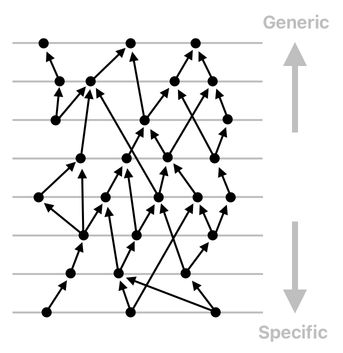

Notice that the "hierarchy" of sandwiches is no longer a tree; it is more of a generic graph, whose branches not only diverge but also converge.

What you are seeing is an example of the so-called "abstraction layers", where upper layers contain relatively generic sandwiches and lower layers contain relatively specific sandwiches.

Each layer is connected to its neighboring layers by means of either divergence (i.e. choice of ingredients) or convergence (i.e. composition of ingredients), or both.

As a result, what we are seeing is a vast, intertwined fabric of sandwiches. Some of them are often preferred over others, depending on how harmonious their ingredients are.

For example, it is not hard to expect that a "bacon cheese sandwich" is much more appetizing than, say, a "steamed beans and mashed potato sandwich".

There are edge cases beyond which the fabric is no longer capable of extending itself, though.

Remember that, in the last article, I mentioned that there are two extreme scenarios called "anything" and "everything", in which the former represents the infinite choice of ingredients, while the latter represents the coexistence of every ingredient?

These two extreme cases can be thought of as the topmost and bottommost tips of the fabric, respectively.

At the topmost is the so-called "sandwich", which is just a shorthand for "anything sandwich". At the bottommost is the "everything sandwich", which is a sandwich containing the entire universe as its core ingredient.

The "anything sandwich" is the ancestor of all sandwiches; it is the ultimate birthplace in which literally anything may potentially fill up the space between the two pieces of bread. The "everything sandwich", on the other hand, is the composition of all types of sandwiches we can ever imagine.

(Will be continued in Chapter 3)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service