Author: Youngjin Kang Date: December 3, 2023

(Continued from volume 17)

From a cognitive point of view, one may rightfully claim that the reality is an ensemble of ideas, and that a complex idea is nothing more than an assembly of simpler ones. The simplest of them are the two sides of a duality.

However, we typically reason in terms of numerical values, each of which belongs to a dimension. This leads us to feel the necessity to search for a bridge between the two theoretical constructs - one which renders an idea as a node in a network (i.e. graph), and the other one which renders an idea as a numerical range residing in a multidimensional vector space.

The portion of the bridge which has been revealed so far tells us that it is possible to translate a set of combinations between emptiness and fullness into a dimension by means of an ordering rule.

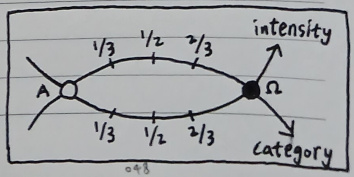

The other portion of the bridge which is yet to be fathomed is the method of representing not just one, but two dimensions - one for quantity (i.e. intensity of sensation), and the other one for quality (i.e. category of sensation). Once we have this figured out, we will be able to define any object of perception as a 2D vector.

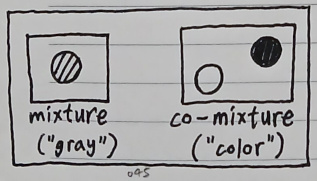

Imagine that we are painting a canvas using only two colors - black and white. If we put these colors at the same spot, we will see that they mix up with each other and turn into a speck of gray. This is an instance of "positional coincidence", and is equivalent to the "AND" operation.

If we put black and white at two different spots, on the other hand, we will see two separate specks of color at two different locations. This coexistence is a neutral (i.e. "co-gray") entity which is not really a "mixture" of the two colors, but their "co-mixture" instead. It is the underlying abstraction called "color" which manifests itself in either black or white by means of the "OR" operation.

Just as we can generate countless shades of gray by mixing ("AND"-ing) a sufficiently large number of black and white specks, so can we generate countless "shades" of the very idea of color itself by co-mixing ("OR"-ing) a sufficiently large number of black and white specks. The former is done by putting black and white at the same exact position on the canvas over and over, whereas the latter is done by scattering black and white all over the canvas, thereby rendering a picture.

Such a piece of fine art is not a single shade of gray (i.e. quantity), but a unique black-and-white scenery involving its own set of figures and their underlying narratives (i.e. quality).

As we have witnessed before, recursive application of the "AND" relation gives birth to varying degrees of quantity. In contrast, recursive application of the "OR" relation gives birth to varying degrees of quality (i.e. categories of imagination), each of which is characterized by a collection of numerous black and white dots which altogether constitute a unique shape.

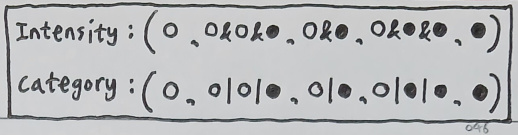

Thus, it is not hard to say that the two ways of synthesizing a pair of ideas (i.e. "AND" and "OR") correspond to the two opposing ways of describing the two dimensions of our perception - intensity (i.e. quantity) and category (i.e. quality). The intensity-dimension is the result of repeating the "AND" process, while the category-dimension is the result of repeating the "OR" process.

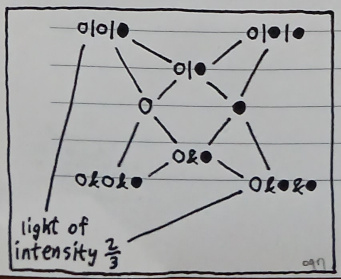

Let us suppose that there is a light of intensity 2/3. And let us also suppose that the category of this sensation, which is called "light", is indicated by the number 1/3. In other words, this particular light is a compound idea which is made out of two numerical values corresponding to two dimensions - one being its intensity (= 2/3), and the other one being its category (= light = 1/3). The intensity value can be defined as "emptiness AND fullness AND fullness", whereas the category value can be defined as "emptiness OR emptiness OR fullness". This is because 2/3 is the 2-to-1 ratio between fullness and emptiness, whereas 1/3 is the 1-to-2 ratio between fullness and emptiness.

This means that the idea of "light of intensity 2/3", as a whole, is simply a composition (i.e. "AND" relation) between its intensity (2/3) and category (1/3).

This sort of reasoning can continue on and on, gradually filling up the two spectrums of manifold values, one being a dimension made up of repeated "AND" procedures and the other one being a dimension made up of repeated "OR" procedures. Anyone may take a pair of values from these two dimensions, fuse them into one, and declare that it is a particular instance of our sensation.

And as we keep connecting such atoms of perception together with additional rounds of "AND" and "OR", we will discover more and more complex ideas, each of which is a collective sum of myriads of elementary (indivisible) qualia.

Previous Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service