Author: Youngjin Kang Date: November 28, 2023

(Continued from volume 16)

In the last volume, I demonstrated the feasibility of interpreting the four primordial ideas as a set of traditional symbols - Water, Air, Earth, and Fire.

Such symbolism should not be taken too literally, though. They simply serve as a storytelling device, contrived to appeal to those who are not so fond of facing abstract concepts directly.

Figurative worldview aside, we ought to be aware of the fact that the origin of multidimensionality has not been explained here yet. Volume 15 already mentioned the feasibility of constructing a dimension and its fine-grained spectrum of values, yet it never described a method through which multiplicity of dimensions could disclose its presence.

Such a realization should probably concern anyone who is convinced that our world of perception reveals itself in discrete categories of qualia, such as visual, auditory, olfactory, and so forth.

Technically speaking, we could just partition our list of grayscale values into multiple segments and pretend that each of them represents a separate dimension. Yet such an approach is more or less a cunning trick, devised to circumvent the problem rather than solving it.

Let us revisit the procedural building blocks which have been introduced so far. Space (i.e. emptiness OR fullness) establishes itself as the "OR" operation between ideas, and Form (i.e. emptiness AND fullness) establishes itself as the "AND" operation between ideas. The former is the birthplace of the dual properties (i.e. emptiness, fullness), whereas the latter is the place in which they fuse into one.

By repeatedly applying the "AND" process over emptiness, fullness, and their AND-constructs, one is able to render a whole sequence of scalar values, each of which can be expressed as a fraction of integers. Such a sequence qualifies as a dimension as long as we exclude irrational numbers from our faculty of reasoning.

The two most extreme poles of our sensation may be worded as "emptiness" and "fullness", respectively. And one may theorize that an intermediate mixture between these two dwells somewhere in between. A decent analogy can be found in the case of auditory sense-data, in which "emptiness" is the lack of any sound, "fullness" is the loudest sound we can ever hear, and their fractional combination is a sound of a moderate volume.

The trouble resides in the plurality of our senses, though, for anyone can ask, "What about the brightness of light? What about hues and saturation of colors? What about the sense of touch, smell, taste, emotions, abstract feelings, and many others?"

So we do need some way of distinguishing different types of qualia from one another, aside from their levels of intensity.

What seems to be a real trick is that each of these types may not exist in complete isolation. Our intuition often drives us to associate certain colors (e.g. red, yellow, orange) with warmth, or crackling sound with squiggly geometric features. They are poetically related to each other in ways which are somewhat loose yet nevertheless explicable in our language.

Such blurriness, though, also evinces us the merit of not being too strict in terms of classification. We have a tendency to split our senses into fundamentally separate domains, yet such means of discretization may not be as axiomatic as it appears to be.

Suppose that a category of sensation is a point on a continuous line. In this context, it is valid to assume that two infinitely close points are equivalent to two categories which are almost identical to each other except for an infinitesimal difference; that is, it is not absurd to say that there could be categories which are qualitatively vague such as "slightly warm color", "slightly visible sound", and so on.

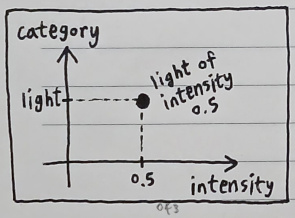

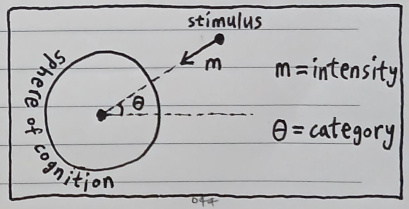

What this suggests is that it is possible to imagine our qualia as points on a two-dimensional plane, whose two coordinate axes represent the intensity-dimension and category-dimension, respectively. The former is the amount of force with which a stimulus penetrates through our sphere of cognition; it is the identifier of quantity. The latter tells us the direction in which a stimulus approaches our sphere of cognition; it is the identifier of quality.

Such a model, as long as it does not ground itself on tautology, successfully reduces our space of perception from one which is N-dimensional (where "N" is the total number of categories and each axis indicates the intensity level of each category) to one which is 2-dimensional (one dimension for the category and the other dimension for the intensity), thereby making it far easier to illustrate our qualia graphically.

The remaining problem is to figure out how to simultaneously express these two distinct dimensions in terms of ideas and their relations.

As we have already witnessed, formulating a single dimension can easily be done by aggregating the "AND" process over the initial duo (i.e. emptiness and fullness) in a recursive manner. The trouble begins when we try to instantiate two dimensions and make them coexist within the same idea space.

(Will be continued in volume 18)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service