Author: Youngjin Kang Date: November 10, 2023

(Continued from volume 12)

The essence of our reality resides in ideas as well as their mutual associations. And since an association presumes the availability of multiple ideas, we cannot deny that the soul of oneness does not cover the whole picture of what can be defined as "real".

Reality stems from existence, and existence stems from our cognizance of difference. And the most elementary form of difference is duality because once we perceive that there are two things instead of just one, we say: "This thing is different from the other". This is the moment at which the heart of our intuition inevitably acknowledges that differentiation is a necessary precondition of plurality.

In the beginning, there is this thing called "duality" which comprises a pair of ideas. Our common sense tells us that such a dichotomous construct alone does not fully explain the sheer complexity of our universe, since our experiences are not a mere collection of coin flips happening between the two most extreme stimuli (e.g. pure pain and pure pleasure).

However, one may still argue that a fine-grained grayscale sensation, too, is essentially just a compound of microscopic dualities, just like a piece of digital data can be formulated as an array of binary digits.

In order to justify such potency of emergence, one must come up with a topological example which is reducible to an assembly of simple dyads yet still reflects the pattern of our cognition.

Suppose that there is an intermediary idea situated right in between the two poles of duality. This third entity presents us with an instance of synchronicity which serves as a unifier of the duo (aka "superposition"). It is also a relation because it tells us how one thing is related to the other.

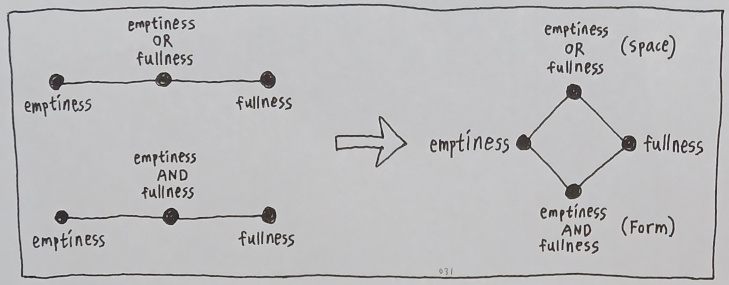

As we fancy that our material universe is nothing more than a combination between two possible states which can be referred to as "empty" (i.e. minimum density of matter) and "full" (i.e. maximum density of matter), we realize that there are two primary ways of defining space. One is that space is a mixture between emptiness and fullness (because "space" has no meaning inside a completely uniform distribution of energy, whether its amplitude be minimum of maximum), and the other one is that space is something which emptiness and fullness both have in common.

The former signifies the idea of "form", which can be phrased as "emptiness AND fullness" coexisting in the same place. The latter signifies the idea of "space", which can be phrased as "emptiness OR fullness" coexisting as optional characteristics which can be added to the same place.

The resulting schema consists of two equally valid types of triad, one descending and the other one ascending the universal hierarchy of beings. The "AND" operator presents us with a specific composition which assigns itself to a lower layer of abstraction by means of combination, whereas the "OR" operator presents us with a shared archetype which assigns itself to a higher layer of abstraction by means of correlation.

The four direct pairs among the aforementioned four ideas (i.e. Emptiness, Fullness, Form (= emptiness AND fullness), and Space (= emptiness OR fullness)) can be illustrated as:

(1) Space <---> Emptiness

(2) Space <---> Fullness

(3) Form <---> Emptiness

(4) Form <---> Fullness

The first duality makes sense because emptiness presupposes the existence of space, for there would be nothing capable of being empty if there were no such thing as space. And space cannot exist without emptiness because a universe solely made out of vacuum of indefinite size, which does not permit any distribution of mass in it, does not endue the concept of distance with any recognizable meaning due to the immeasurability of uniformity, thus preventing the definition of space from establishing itself (because space is defined in terms of distances).

Fullness, too, is rooted in such a presupposition for an equivalent reason, which subsequently validates the second duality.

The overall implication of the two statements above is that both emptiness and space, as well as fullness and space, are complementary pairs which cannot be broken down to isolated thoughts.

The third and fourth dualities make sense because the presence of emptiness/fullness depends on the availability of a form, which is a morphological construct comprising spatial points that are either occupied or unoccupied by mass. Without a form, space is nothing more than a uniform field. Whether such a field is "completely empty" or "completely full" does not mean anything from a functional standpoint.

This is reminiscent of the fact that an electric circuit which operates under the source voltage of 5V and ground voltage of 0V exhibits the same exact behavior as one with the identical configuration which operates under the source voltage of 0V and ground voltage of -5V. A quantitative value itself is just a linguistic construct; it is the difference between values which gives birth to observable phenomena.

(Will be continued in volume 14)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service