Author: Youngjin Kang Date: November 7, 2023

(Continued from volume 11)

So far, it has been suggested that a set-based model of ideas is more elegant than its multidimensional counterpart because it more directly derives its symbolic structure from the core of reason. Unlike dimensions which necessitate the use of numerical quantities, sets more concisely reflect the way in which we classify our thoughts.

It is the very notion of classification itself and its ensuing "multitude of beings", however, which even set theory fails to illustrate from an ontological standpoint. Why do we believe that there are "many things", as opposed to "one thing"?

Perhaps the simplest explanation is that if we do not presume the plurality of existence, there will be no way for us to justify any thought process. What is the point of thinking, if there is only one all-encompassing essence of being which provides absolutely no room for any comparison?

This pragmatic morsel of wisdom, however, inevitably generates the impression that it merely puts a bandage on an intellectual hole in order to deliberately ignore a fundamental inquiry which deserves to be answered.

When it comes to exploring the origin of what makes us think the way we think, one cannot overlook the importance of stepping aside from the pool of manifold imagination and begin reconstructing one's foundation of logic from the most minimalistic building blocks one can ever conceive, for it is how we prevent ourselves from getting stuck in the midst of complexity.

Thus, it is crucial to unlearn the theoretical architecture which has hitherto been described for now and start afresh from a blank sheet of paper.

At the genesis of one's cognizance, there is unity. It is the heart of our knowledge - the absolute point of universal symmetry at which everything comes and goes at once. It is the source of oneness which fills up the entirety of space and time, yet possesses neither volume nor movement. It is nothingness itself, which is so utterly nil that we cannot even define it (because even a definition is "something" which must be capable of distinguishing itself from nothing).

In this spirit of singularity, we have nothing to conceive in our mind due to the lack of any way of "not" conceiving anything, for there must be a boundary of contrast between an act and the absence of an act in order for us to let ourselves state that something exists. As long as everything is one, there is no contrast. And where there is no contrast, existence is nonsense.

Therefore, the bare minimum of syntax which we must cogitate for the purpose of establishing some form of ontology is that of dualism - the opposition between a pair of entities, each of which rationalizes its own presence based upon its differentiation from the other.

There are numerous types of dualism, such as good and evil, brightness and darkness, positivity and negativity, proximity and distance, fullness and emptiness, action and reaction, push and pull, up and down, etc. Every one of them comes as a pair, since neither of its two halves makes sense without the other half.

A major problem lies on the matter of configuration, though. When we desire to express the nature of dualistic properties as a schema rather than an assortment of vague metaphors, what we invariably encounter is an enormous list of alternative choices, every one of which claims its own right to be considered legitimate.

I have been basing my system of reasoning on the belief that everything which constitutes our reality is reducible to an assembly of ideas and their associations; such an assumption narrows down our spectrum of choices, yet it still leaves us with a number of equally feasible symbolic arrangements.

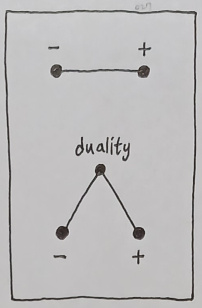

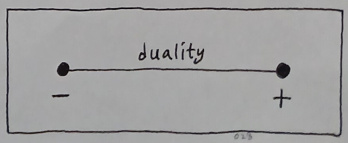

For example, if there are two ideas corresponding to two mutually opposing forces, should we say that they are simply associated with each other? Or, should they be associated with yet another idea called "duality" which explicitly indicates that the two are supposed to make up a dyad?

The answer is that it depends on the meaning of association. If it is synonymous with "mutual contrast", we will be able to ensure that a single association is all we need to express dualism. If not, we will need an intermediary idea to denote such a relation.

And here is a clue which helps us solve this dilemma. It has been assumed that oneness is not a sufficient condition for existence because it requires us to think of nonexistence as the complement to existence, the process of which presupposes the availability of multiple entities. Thus the very notion of distinction, hence its underlying suggestion of duality, dictates that our most primeval units of being (i.e. ideas and associations), in order for them to "exist", must inherently pose dualism in them.

And since an idea itself does not enable the conception of plurality (because nothing differentiable arises from where there is only one idea), association is what duality is.

(Will be continued in volume 13)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service