Author: Youngjin Kang Date: July 2, 2024 - July 31, 2024

This is a mathematical interpretation of David Hume's philosophy. It is mostly based upon my personal analysis, so please take it with a grain of salt.

I drew most of my inspirations from his book, "An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding". For more information, visit Here.

Hume's empiricist worldview begins with a hierarchy of concepts.

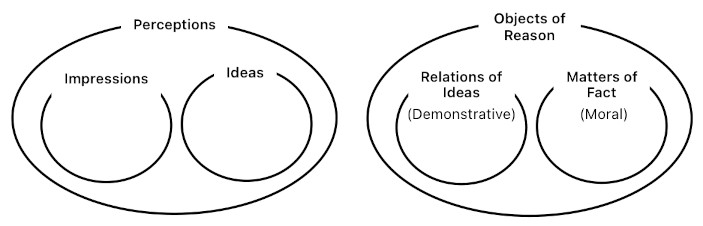

There are two major types of components in his domain of knowledge. One is "perceptions", and the other one is "objects of reason". Perceptions are the atoms of the mind, whereas objects of reason are molecules which can be formed by bonding those atoms together.

A perception is any "thought" we can conceive in our minds. It belongs to either one of the two categories - impressions and ideas.

An impression is a direct stimulus received by our sense organs. Things we directly see, hear, smell, taste, and feel are all impressions.

In contrast, an idea is an afterthought on the impressions we received. For example, what we see is an impression, but the recollection of what we just saw is an idea. Impressions are vivid, while ideas are dim.

Objects of reason can be subdivided into two categories - "relations of ideas" and "matters of fact".

A relation of ideas is a result of pure logic, such as a mathematical theorem which manages to prove itself based upon a set of ideas only, without relying on the presence of external stimuli. A matter of fact, on the other hand, requires a considerable amount of empirical data to validate itself (like the law of gravitation).

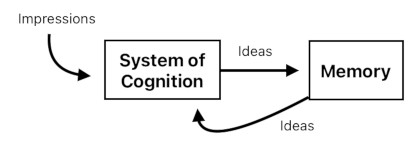

Hume's definition of "impressions" and "ideas" provides us with a rudimentary ground of logic, upon which we can formulate a model of how we sense and recall our own thoughts.

Impressions are what we typically refer to as "sensory stimuli". These are the most immediate and piercing kind of perceptions which we feel with the utmost degree of intensity.

Ideas, on the other hand, are byproducts of impressions. They linger in our minds like ghosts, which occasionally touch our feelings but to a much lesser degree. Unlike impressions which are momentary, ideas stay in the person's memory and get recalled on demand.

In a way, therefore, ideas are Lego bricks which can fit one another nicely in our minds, whereas impressions are just raw plastic ingredients which are yet to be molded into such bricks.

According to Hume's philosophy, each impression generates its corresponding idea when it enters our domain of cognition.

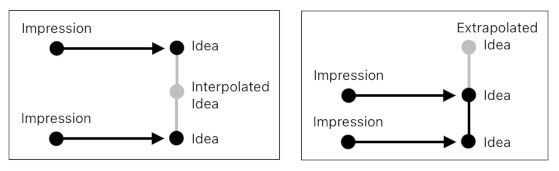

However, he also mentions that the relation between impressions and their ideas is not necessarily one-to-one. There may as well be cases in which a wide spectrum of ideas manage to emerge from a relatively few impressions.

An impression of "light blue" and an impression of "dark blue", for example, may allow us to imagine an intermediate shade of blue (by mixing the qualities of light blue and dark blue) and remember it as a distinct idea. This lets us picture the full spectrum of blue without having to directly sense every single one of its variants via external stimuli.

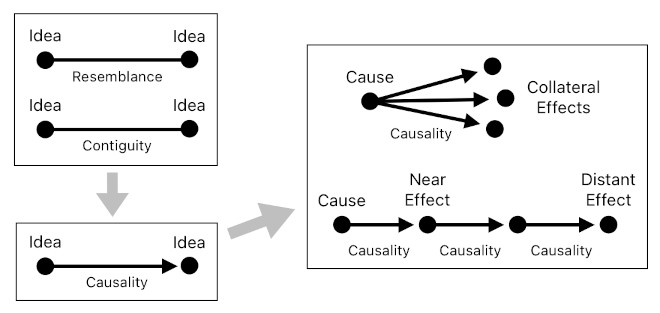

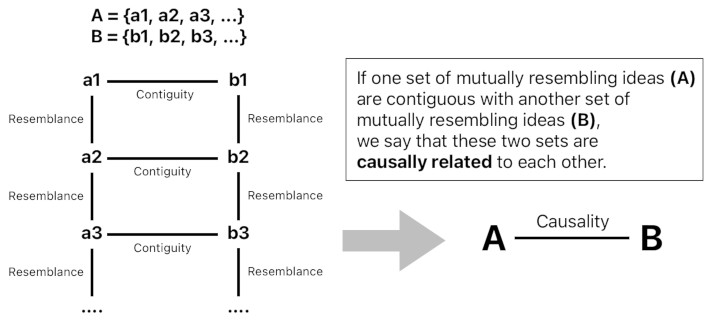

We assign meaning to our ideas by establishing relations between them. In Hume's model of the human mind, there are three fundamental types of such relations - resemblance, contiguity, and causality (aka "cause and effect").

Resemblance tells us that two ideas are qualitatively similar to each other (such as two slightly different shades of blue). This is something we can immediately tell from our perceptions.

Contiguity tells us how close two ideas are to each other in spacetime. This, too, is something we can immediately tell from our perceptions.

Causality, however, is not something we can identify in such a straightforward manner. We must derive it from the other two types of relations (i.e. resemblance and contiguity).

An idea alone does not have the word "cause" or "effect" written on its face, and the only way for us to prove that an idea "causes" another idea is that one of them frequently precedes (or succeeds) the other in spacetime.

Also, since it is almost impossible for us to reproduce the same exact idea over and over in our material world (which is plagued with all sorts of random noises such as acoustic waves, electromagnetic disturbances, thermal noise, etc), we must rely on our belief that similar causes are likely to produce similar effects.

This leads us to the conclusion that, if a set of mutually resembling ideas are contiguous with another set of mutually resembling ideas, we can say that these two sets are causally related to each other.

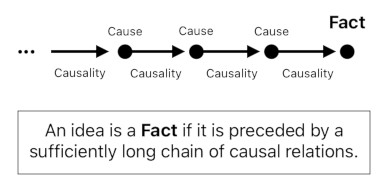

What is a "fact", really?

There are many ideas in our domain of reason, yet the boundary between ones that are supposed to be "facts" and ones that are mere personal feelings often looks a bit fuzzy.

Hume's philosophy tells us that an idea can be considered a "fact" if it is caused by a sufficiently large number of causes (e.g. preceded by a sufficiently long chain of causal relations).

Each cause works as a proof of the idea's truthfulness. The more causes there are, the more confidently we are able to say that the idea is true. If it is so true that its truthfulness is hardly questionable, we say that the idea is a "fact".

People who know how a blockchain works (such as Bitcoin or Ethereum) will easily come to the realization that ideas are reminiscent of blockchain transactions, and that a "fact" is basically a transaction which has been mined (verified) and is given credit by a long chain of preceding blocks.

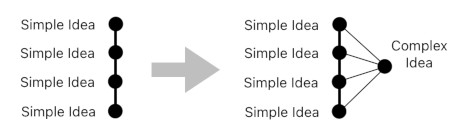

In "A Treatise of Human Nature", Hume makes a clear distinction between simple and complex ideas.

Based upon his rejection of the infinite divisibility of our sense-data, he says that "simple ideas" are ideas which cannot be further divided into its component parts, meaning that they are the "atoms" of our mind.

Examples of simple ideas include the primary color components (e.g. red, green, and blue), musical notes, and other irreducible units of sensation.

"Complex ideas", on the other hand, are groups of simple ideas. Each complex idea is a product of synthesis among two or more simple ideas. It is also possible to group complex ideas to form even more complex ideas.

A simple impression (i.e. external stimulus) gives birth to a simple idea. A multitude of simple ideas, then, give birth to complex ideas based on the way in which they are related to each other.

A group of simple ideas are able to produce a complex idea. A group of complex ideas, too, are able to produce yet another complex idea which is even more complex than the preceding ones.

In general, therefore, we can say that a group of ideas with appropriate relations, whether they are simple or complex, are capable of generating a complex idea whose level of complexity is slightly higher than them.

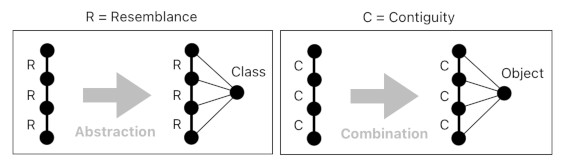

There are two ways in which a complex idea may emerge - abstraction and combination.

When you see a group of slightly different shades of blue, you will recognize that they closely resemble each other. From this, you can conclude that they all belong to a class of objects called "blue". This is an example of abstraction.

When you see a lump of various colors, on the other hand, you will recognize that the individual colored spots do not necessarily resemble each other but are nevertheless very closely packed together in physical space. From this, you can conclude that they all belong to the same object. This is an example of combination.

There are two primary types of relations between ideas - resemblance and contiguity. Resemblance indicates conceptual proximity, and contiguity indicates physical proximity.

Just like resemblance and contiguity can connect simple ideas, they are able to connect complex ideas as well.

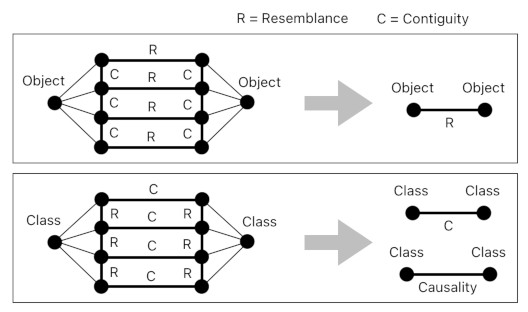

An object is a complex idea which is based off of a set of contiguous ideas. When two objects have sufficiently many pairs of resembling ideas between them, they resemble each other.

A class is a complex idea which is based off of a set of resembling ideas. When two classes have sufficiently many pairs of contiguous ideas between them, they are contiguous to each other.

A contiguity between two classes may also be referred to as "causality" (i.e. One of them is either the "cause" or "effect" of the other).

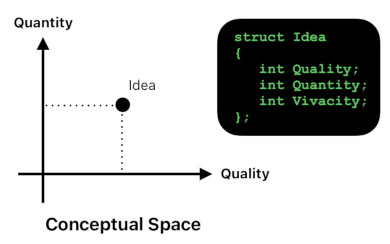

According to Hume's argument in "A Treatise of Human Nature", every idea (or impression) must possess its own quality and quantity.

An idea's quality denotes the category of sensation to which it belongs, such as "brightness", "musical pitch", or "temperature".

An idea's quantity denotes its quality's intensity level. For instance, if there is an idea whose quality is "temperature" and whose quantity is "30", we may consider this idea as a sensation of warmth which is 30 degrees in temperature.

Hume says that an impression is basically the same thing as an idea (i.e. It has its own quality and quantity), except that it is much higher in "force and vivacity".

Therefore, I personally find that it is much more convenient to consider an impression as an idea whose level of vivacity is sufficiently high.

When expressed in the language of computer science, both impressions and ideas are mere instances of the same data structure called "Idea", which contains 3 integers - Quality, Quantity, and Vivacity.

Metaphors are everywhere. They appear in poetry, novels, songs, and many other forms of media. However, they are often accused of being irrational.

Hume's philosophy suggests otherwise. It is possible to define a metaphor on a rational basis.

An idea has a location in conceptual space, which is composed of two dimensions called "quality" and "quantity". Quality indicates the category of sensation (e.g. brightness, loudness, temperature, etc), and quantity indicates its level of intensity.

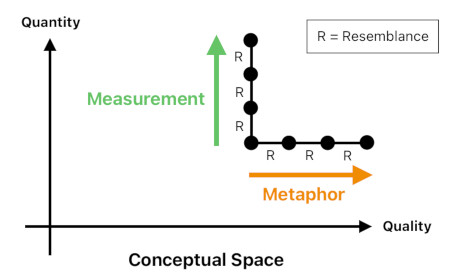

We say that there is a resemblance between two ideas when they are close to each other in conceptual space. There are two types of resemblances: (1) Resemblance in quality, and (2) Resemblance in quantity.

Coldness and hotness do not resemble each other quantitatively, since their intensity levels (i.e. temperature) differ significantly. However, they resemble each other qualitatively because they both belong to the same category called "temperature".

On the contrary, red and hotness do not resemble each other qualitatively because they belong to two drastically different categories of sensation. However, they resemble each other quantitatively because the high emotional intensity of red is similar in magnitude to the high temperature of hotness. This is what we call "a metaphor".

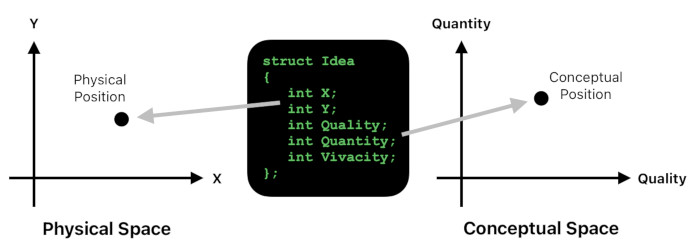

An idea must have its own quality and quantity. However, we ought to be aware that it must also have its own physical location in order for the mind to conceive it.

For example, when you are imagining a colored point, you cannot do it without locating it somewhere inside your imaginary field of vision.

Hume suggests that, in order for an idea to "exist", we must be able to perceive it either through external senses or our own imagination. Therefore, an idea is required to have a pair of positions - one in conceptual space, and the other one in physical space.

It may theoretically be insisted that it is also feasible to formulate "pure ideas" which belong to either physical space or conceptual space but not both. Such constructs, however, are not directly sensible and thus do not belong to the domain of cognition.

How to compute the position of an idea?

The position of a simple (atomic) idea does not have to be computed. It is simply given to our faculty of senses the very moment it is perceived.

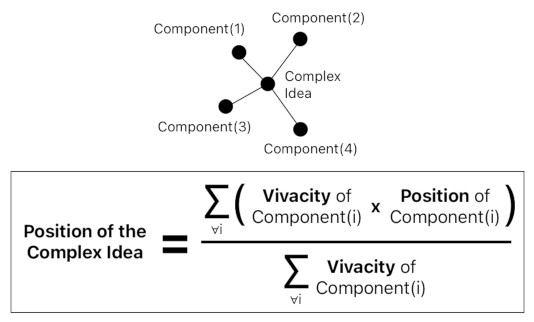

The position of a complex idea, on the other hand, must be computed based upon those of its component ideas.

An object in physical space appears to be a single point when viewed from a sufficiently long distance. The physical position of such a point is the center of mass of the object's components in physical space.

Meanwhile, the object's individual color spots "average out" when they are condensed into a single point. This means that its conceptual position is the center of mass of the object's components in conceptual space.

The "mass" of an idea is its vivacity.

Whenever we communicate, we use words and symbols to reference our ideas.

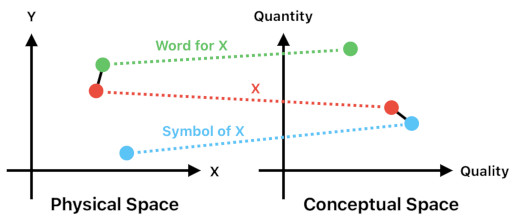

The difference between a word and a symbol can be found in the two fundamental relations between ideas - contiguity (i.e. proximity in physical space) and resemblance (i.e. proximity in conceptual space).

When you open up a children's book intended to teach basic English words, you will see that there are lots of images with words next to them. For example, if there is an image of fire, the book will also put the word "fire" right next to it in order to teach the child that the word "fire" is associated with the appearance of fire.

Here, the word "fire" and the appearance of fire do not visually resemble each other, but the child nevertheless learns that the former indicates the latter because these two things have been displayed contiguously in physical space (i.e. page of the book).

What about a symbol? Here is an example. An airplane's safety manual typically uses an icon of fire (aka pictogram) to reference real fire.

In this case, the icon is a symbol of fire, not because we have necessarily seen this icon appearing right next to real fire in physical space, but because we know that these two things visually resemble each other.

Therefore, a word is an idea which references another idea by means of proximity in physical space, whereas a symbol is an idea which references another idea by means of proximity in conceptual space.

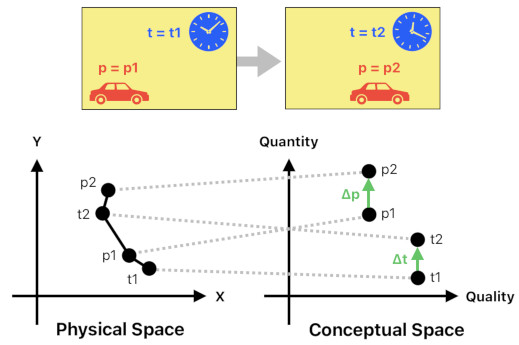

When there is a moving car, how do we measure its speed?

Suppose that we have two snapshots available, one of them showing the car's position at one point in time, and the other one showing the car's position at another point in time.

Let us refer to the first snapshot's position and time as (p1, t1), and the second snapshot's position and time as (p2, t2). Since p1 and t1 appear together in the same snapshot, we know that they are contiguous. And since p2 and t2 appear together in the same snapshot, we know that they, too, are contiguous. Furthermore, since the two snapshots are juxtaposed right next to each other, they are contiguous as well.

And since they (p1, t1, p2, t2) all make up a single body of contiguities, we can tell that they all belong to the same context.

t1 and t2, although they are not physically nearby, belong to the same "quality" in conceptual space (because they are both time values). From this coincidence, we are able to tell that their quantities are comparable. The result of their comparison is the change in time (Δt = t2 - t1).

Similarly, p1 and p2 belong to the same "quality" in conceptual space (because they are both position values), so we are able to tell that their quantities are comparable as well. The result of their comparison is the change in position (Δp = p2 - p1).

The car's speed according to the two snapshots, then, is the ratio between Δt and Δp (i.e. ratio between the lengths of the vertical line segments in conceptual space which are associated with the two snapshots).

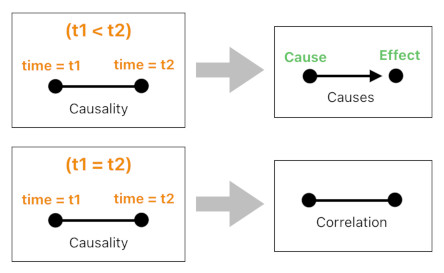

Ideas often represent events, and we know that the human mind is prone to associate events with one another in terms of cause and effect (i.e. causality).

Hume says that, by making a sufficient number of observations, we are able to notice a "constant conjuction" between two classes of objects. Hence, he explains that this "constant conjuction" is the data from which we draw the notion of causality.

In order to decide which event is the cause (or effect) of the other, however, we should make an additional analysis. It is the concept of "precedence" to which we ought to pay attention, since it is what gives a direction to the causal relation.

If there is a relation of causality between X and Y, we say that X must be the cause of Y if X precedes Y in time, and vice versa.

This endows the chain of events with a fixed direction of progress, flowing from the past to the future.

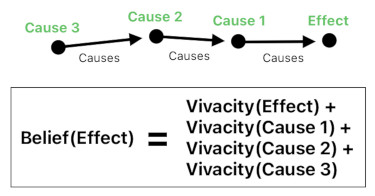

It is possible to compute the amount of belief in an idea.

Our minds are populated by various ideas. Some of them are considered fictitious, while others are considered real. We make such a distinction based upon the amount of belief in each idea.

Imagine that an idea is preceded by a chain of causes (i.e. causal relations). The longer and more vivid the chain is, the more we are convinced that the idea is "real". And the shorter and less vivid the chain is, the more we are convinced that the idea is "fake".

Thus, the total amount of belief in an idea is the sum of vivacities of its preceding ideas, plus its own vivacity.

An impression (i.e. external stimulus) is "real" because, although it is not preceded by a chain of causes, its own vivacity is so sufficiently high that it easily conjures up a strong sense of belief.

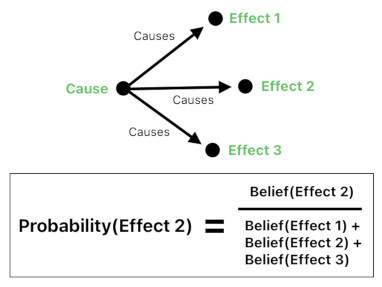

When a cause is given, how do we measure the probability of occurrence of each of its effects?

Our minds are filled with ideas, and ideas usually represent events. Our belief in the occurrence of an event possesses its own numerical quantity, which can be computed by the "Belief(X)" function where X is the event of interest.

Given a cause, we say that the probability of occurrence of one of its potential effects is the proportion of the belief in the given effect with respect to the sum of the beliefs in all the potential effects.

The more frequently we observe an event, its vivacity increases. And the less frequently we observe an event, its vivacity decreases.

Since the amount of belief in an event is the sum of the vivacities of its history, we can say that more observation yields higher probability and less observation yields lower probability.

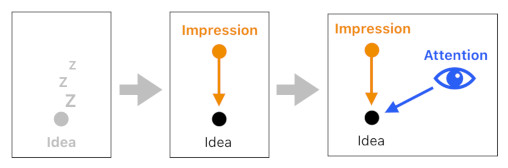

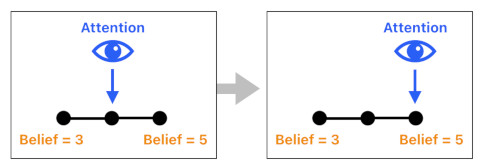

A person's attention is a pointer which points to an idea.

Ideas, which fill up the mind's mental space, stay inactive as long as they are being neglected. It is because their vivacity levels are zero by default.

When an external stimulus enters the person's sensory organ, an impression gets created. It sticks itself to the corresponding idea and breathes vivacity into its mouth, thereby making it alive.

At the same time, the impression attracts the mind's attenion and induces it to point to the idea. The impression soon dies out (due to the cooling down of the stimulus), but the attention remains for a while, cogitating the idea to which it was summoned.

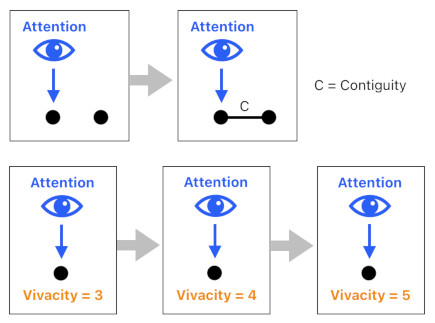

A person's mind contains at least one active agent of cognition called "attention". An attention points itself to one idea at a time.

There may as well be multiple attentions navigating the person's mental space concurrently. If it is the case, we will refer to them as "primary attention", "secondary attention", and so on.

An attention performs two major jobs while it is pointing to an idea.

(1) It connects the idea with nearby ideas. In physical space, such a connection is called "contiguity". In conceptual space, such a connection is called "resemblance".

(2) It boosts up the vivacity level of the idea.

The more we pay attention to certain ideas, the more vivid they get. This, in turn, strengthens our belief in these ideas.

Ceremonies and rituals are important in human society because citizens need to share a set of common beliefs. Such activities basically "recharge" the vivacity levels of a set of ideas, ensuring that their connections are firmly fixed in our minds.

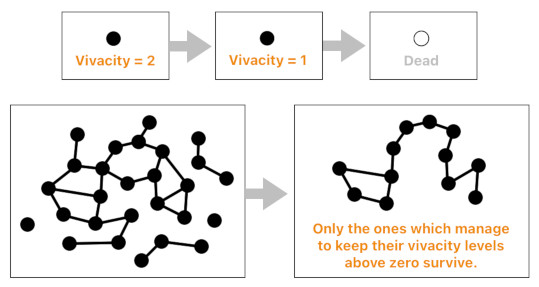

The dots you see here are ideas. Ideas can be connected to each other (denoted by line segments) if they are either contiguous in physical space or if they resemble each other in conceptual space.

The mind contains a self-moving agent called "attention" which constantly crawls the vast network of ideas and their connections, boosting their vivacity levels.

Each idea possesses its own "belief" number. This number tells us how strongly the mind believes in the existence of the idea.

When the attention encounters multiple alternative pathways through which it can move, it tends to move toward nearby ideas with higher beliefs than those with lower beliefs.

Over time, this tendency forces only a few strongly believed ideas to survive and all the other ideas to die out. It is reminiscent of gas clouds in space gradually being condensed into a few dense balls of mass (i.e. planets).

A person's mind is like a galaxy; it is a dense celestial body of innumerable ideas, all shining desperately to be embraced by the attention of the consciousness.

The mind must pay attention to an idea at least occasionally in order to keep it alive. Otherwise, its vivacity will decrease over time and, once it reaches zero, it will kill the idea.

Unfortunately, the mind can pay attention to only a small number of ideas at a time. So, even if the mind happens to have a vast cloud of ideas (due to a sudden appearance of a huge number of external stimuli, for instance), time will eventually do its job of "thinning out" such a cloud into a rigid skeleton of only a selected few ideas which are deemed way more important than others.

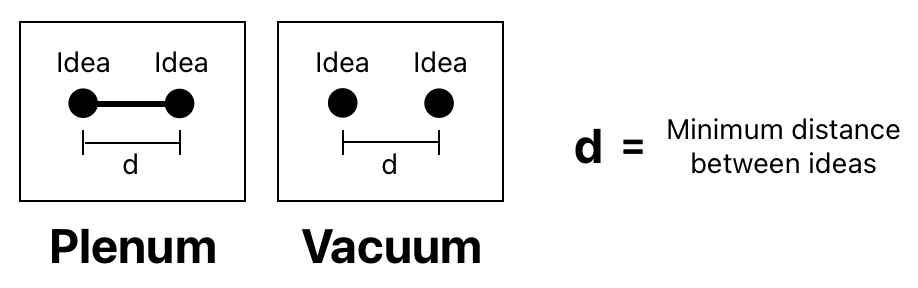

Hume's rejection of the infinite divisibility of matter in our minds eventually leads us to the conclusion that ideas must be discrete and finite in nature.

The reason is simple. A brain does not possess infinite processing power, so it cannot possibly perceive an infinite number of ideas.

Therefore, our mental space must be discrete (i.e. not continuous), and must be enclosed by finite boundaries beyond which no further ideas are conceivable (We cannot see things whiter than white itself, for instance).

What this means is that there must be a "minimum distance between ideas". No two distinct ideas can ever be closer than this.

If a pair of ideas separated by the minimum distance are connected to each other (either via the relation of contiguity or resemblance), we can define this interval as the most basic unit of "plenum" (i.e. filled space).

If a pair of ideas separated by the minimum distance are disjoint from each other, we can define this interval as the most basic unit of "vacuum" (i.e. empty space).

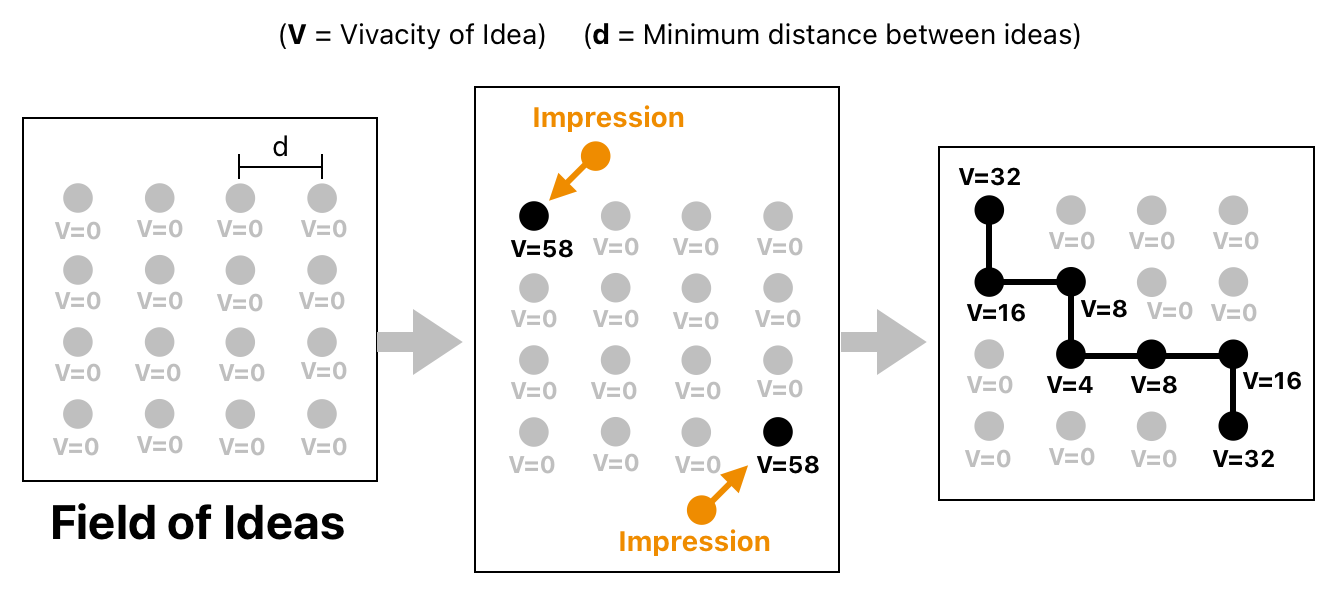

Since ideas are discrete, we can imagine the mind as a vast field of ideas which are placed at regular intervals. The size of each interval is the minimum distance allowed between a pair of ideas.

Most of these ideas, however, are in sleep because their vivacity levels are zero. The mind cannot perceive them because they "do not exist".

External stimuli, which enter the mind via sense organs, give birth to impressions. These impressions, in turn, pump up the vivacity levels of their respective ideas.

The vivified ideas attract the mind's attention. The attention, then, connects these ideas by "smearing" their fluids of vivacity toward each other. If they are too far apart, however, there won't be enough vivacity to spread and the connection will fall short.

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service