Author: Youngjin Kang Date: June 27, 2024 - July 26, 2024

This is a collection of game design concepts.

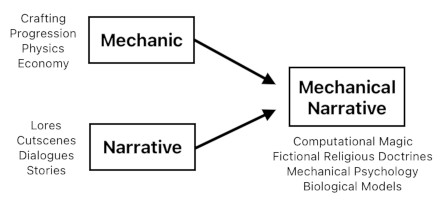

A game is usually a combination of two factors - mechanics and narratives.

Mechanics represent the systematic aspects of the game, such as physics, AI, crafting rules, progression curves, and others which rely on the knowledge of math/engineering.

Narratives represent the volitional aspects of the game, such as lores, stories, personalities, goals, and others which rely on the knowledge of arts/humanities.

A problem we often experience is that it is too tricky to fit these two together in one place. Many ambiguous cases are prone to arise, such as:

(1) Having a cool story (narrative) for a video game, but not knowing how to turn it into gameplay (mechanic).

(2) Knowing how to implement a clever enemy AI (mechanic), but not knowing how to design an appropriate enemy character for it (narrative).

(3) Having an interesting NPC with a unique personality (narrative), but not knowing which in-game role it ought to play (mechanic).

A solution is to start designing the game with building blocks which can both be considered mechanics and narratives at the same time (aka "mechanical narratives").

If we start by laying out the game's narratives first, it will be difficult to devise mechanics which are compatible with the given narratives. If we start by laying out the game's mechanics first, on the other hand, it will be difficult to devise narratives which are compatible with the given mechanics.

Such a dilemma can be bypassed by simply collecting a number of "mechanical narratives" and assembling them together.

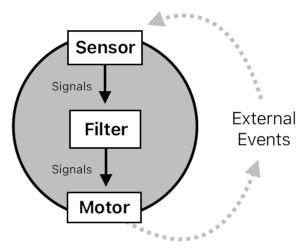

In general, a gameplay agent can be constructed by assembling 3 types of modules - sensors, filters, and motors.

Sensors collect data from the environment, filters process the data (for analysis), and motors trigger the agent to take actions based upon the filtered data.

Here is an example. Imagine that there is an anti-aircraft gun whose role is to shoot down enemy airplanes in range. We can model this gun as a composition of:

(1) A sensor (i.e. radar) which detects anything within the specified range,

(2) A filter (i.e. computing module) which looks up the database to see if the detected object is an enemy airplane, and

(3) A motor (i.e. the gun itself) which fires bullets at any object which is identified as an enemy airplane.

The gun detects an aircraft, checks to see if it is an enemy, shoots at it if so, and then detects another aircraft, checks to see if it is an enemy, shoots at it if so, and then detects another aircraft... and so on.

This is just a simple example. For more complex behaviors, you may as well equip it with multiple sensors (e.g. radar, camera, antenna), multiple filters (e.g. distance filter, look-angle filter), multiple motors (e.g. gun, horizontal rotor, vertical rotor, ammunition reloader), etc.

Such a multitude of modules can then communicate with one another by means of series connections, parallel connections, or both.

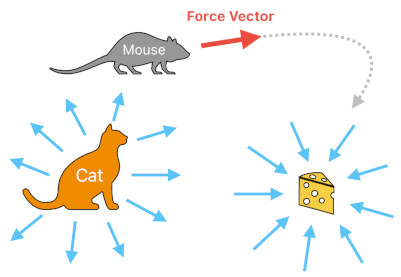

Psychological force field is a useful concept in game design.

We typically imagine each individual game character as an observer, equipped with its own independent mind. It continuously scans the environment and makes decisions off of it.

Each observer carries its own psychological force field which permeates the entirety of the game world. Every entity other than the observer itself essentially "warps" the field nearby, modifying the magnitudes and directions of the force vectors which guide the observer's movement.

A repulsive entity adds outward forces to the field, whereas an attractive entity adds inward forces to the field. This makes the observer move away from repulsive entities and closer to attractive entities.

Whether an entity is repulsive or attractive is determined by the observer's personal preference.

The force that is to be applied to the observer can be computed by the function "PsyForce(id, X, Y)", where "id" is the unique ID of the observer and (X, Y) is the observer's current position. This function returns the psychological force vector which gets added to the observer's net force.

A real life example of psychological force field is Feng Shui, where architectural patterns are believed to shape the field in which the residents of the house reside, thereby influencing the way they behave.

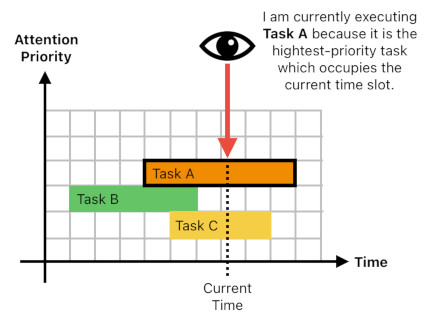

A parallel-attention timeline is a pretty useful tool to use in gameplay AI.

It starts from a simple analogy.

When I am stirring a pot of spaghetti while also heating a plate of frozen garlic bread in the oven, you can say that I must be multitasking.

However, it should be noted that I am paying way more attention to the pot of spaghetti than to the oven because the latter basically takes care of itself and only demands occasional supervision.

When designing a game, it is convenient to assume that each game character carries its own schedule in its mind, filled with tasks which start and end at their own designated points in time.

It is sometimes even more desirable, though, to model a schedule not as a one-dimensional queue of tasks, but as a two-dimensional grid in which each column represents a time slot and each row represents what could be referred to as "attention priority".

A character which follows this two-dimensional schedule always runs the task which occupies the highest row (i.e. highest attention priority) among all the tasks which occupy the current time slot.

Whenever an "attention trigger" (i.e. any object which demands attention) tries to register a new task to the schedule, the schedule will either ignore this new task if it happens to collide with an existing one, or proceed to register it if not.

Each task possesses its own intrinsic attention priority (i.e. row) which cannot be modified.

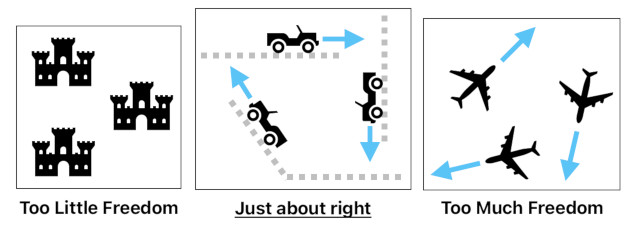

Both too much freedom and too little freedom are undesirable in gameplay.

Suppose that there are enemy characters whom the player must defeat in order to finish the level.

If the enemies are able to move in any direction, it will be a bit too bland because it reduces the functional significance of the level's peculiar spatial configuration (e.g. If you are being chased by an enemy who can only move horizontally, you can take refuge in a vertical space).

If the enemies are completely immobile, on the other hand, it will be pretty bland as well because it makes gameplay less dynamic.

A nice middle ground which leverages the benefits of both is to confine each enemy's locomotive freedom to a set of simple pathways, as though it is a train following a railway.

This mixed approach has 3 main advantages:

(1) It makes it easy to diversify enemy behaviors and introduce a wide variety of in-game strategies.

(2) Its pathfinding algorithm is easier to implement and way less computationally expensive than, say, the A-Star algorithm.

(3) It prevents extreme gameplay scenarios, such as letting the player be completely surrounded by a truckload of enemies because they always keep chasing the player without a pause. By limiting each enemy's maximum range of movement, we can spread out the distribution of enemies throughout the level and prevent them from concentrating too much in one place.

When it comes to designing gameplay systems, it is often useful to model each game character as a state machine (i.e. an object with a set of possible states). There are more advanced models indeed, but state machines usually suffice for fairly simple purposes.

Such a state machine typically comprises the character's action states, such as "idle", "attacking", "stunned", "wandering", and so on. However, this representation does not reflect the character's inner psychological states such as emotions.

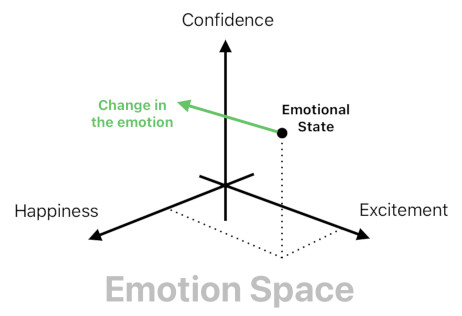

In order to give depth to the game's narratives, we must let game characters have their own emotions. And this can be done by designing each character as an emotional state machine.

An emotional state machine resides in a 3D space called "emotion space", whose 3 spatial axes represent the character's happiness, excitement, and confidence.

The characters's emotional state is a point in the emotion space, and a change in the emotion is the same thing as a displacement of the point from one location to another.

When happiness, excitement, and confidence are all low, the character is depressed and timid. When happiness, excitement, and confidence are all high, the character is fascinated and arrogant. When happiness is high but excitement and confidence are low, the character is quietly happy in its selfless devotion. And when happiness and excitement are low but confidence is high, the character is in the mood of Squidward.

You can change the emotion's current state by applying a "psychological force" to it. The way you do it is to put the emotion's position under a psychological force field.

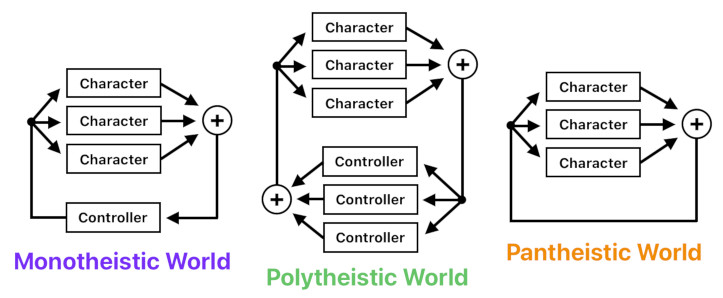

Designing a game is essentially the same thing as designing your own virtual world.

A game is a world which is governed by its own set of natural laws. And the manner in which these laws are being enforced largely depends on the manner in which the developer has initially configured the world.

Game worlds come in different types, each of which pertains to a particular theistic worldview.

Inside a monotheistic game world, a single control module regulates the feedback loops of the game characters.

Inside a polytheistic game world, multiple control modules regulate the feedback loops of the game characters.

Inside a pantheistic game world, the game characters' feedback loops are not being regulated by any external module; the characters themselves are their own regulators.

One of the main advantages of using either a monotheistic or polytheistic system is that it allows the gamemaster to occasionally override the game's default laws by means of admin privilege. In computer science, it is called "miracle".

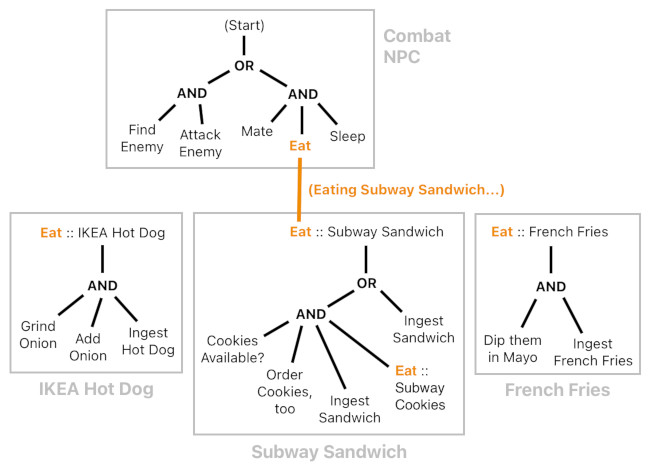

Behavior trees are useful in game AI. You can implement a wide range of complex decision-making agents based upon them.

Sometimes, however, we feel overwhelmed by the urge to make a behavior tree unreasonably enormous when there are way too many types of items with which the agent is supposed to interact.

For example, imagine that a game character has a behavior tree which involves a task called "eat". In order to tell the character exactly what to do when it runs this task, the "eat" node must be able to handle all possible ways of eating, such as how to eat a salmon, how to eat a donut, how to eat a taco, and so on.

Thus, it is oftentimes convenient to make behavior trees modular, so that a tree of tasks that is specific to the object of interaction can simply reside within the object, temporarily stick itself to the character's "eat" task during the interaction, and then depart once the interaction is over.

One thing I learned while developing and publishing indie games, was that a game needs to have its own brand in order to be truly successful.

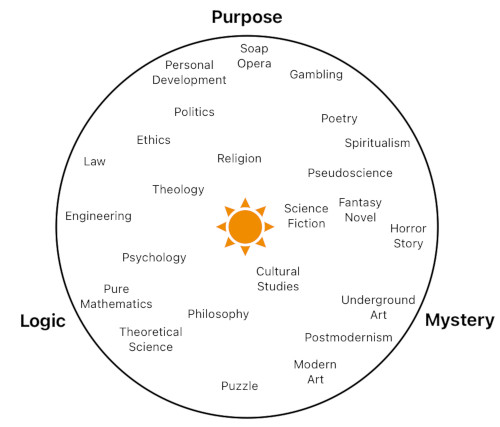

Creating a brand is such a monumental challenge. One cannot just put a bunch of buzzwords together and expect it to leave a lasting impact upon the heart of the audience. In my opinion, a great brand requires 3 major elements: Purpose, Logic, and Mystery.

A brand needs a purpose because otherwise the customer won't be encouraged to partake in its narrative. Without a purpose, there is no need to support the brand's growth by any means.

A brand cannot flourish without any logic either. It must have a logically sound solution to fulfill the said purpose. Our reason must be able to grasp it, for otherwise everybody will be left confounded.

However, a brand also ought to preserve a decent amount of mystery in it. Even a perfectly logical solution, guaranteed to solve the most urgent problem in the most quintessential way, won't attract the audience if they are not given their own roles to participate in a journey to freely explore the unknown and discover hidden treasures.

In general, I believe that the most appealing brand must have its own purpose, logic, and mystery in equal measures. This corresponds to the center point of the circular diagram I have shown here (denoted by the Sun).

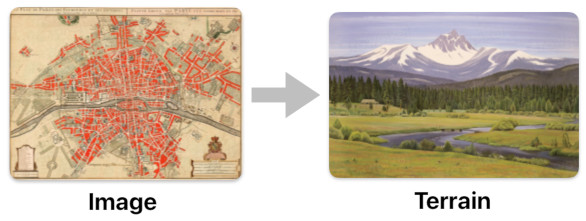

Using an image to generate a game map is sometimes a good idea.

Suppose that your game comprises one vast terrain, modeled as a 2D voxel grid.

All you need to do is create an image and simply assume that its pixels represent to the terrain's voxels.

Each pixel's brightness may indicate the terrain's height. This can be graphically implemented by rendering the terrain as a grid of quads and letting the vertex shader set the y-coordinate of each vertex based on the corresponding pixel's brightness.

Each pixel's saturation may indicate the density of props, where low saturation means low probability of spawning a prop at the pixel's location, and high saturation means high probability of spawning a prop at the pixel's location.

Lastly, each pixel's hue may indicate the terrain's biome type, where "green" means forest/meadow, "orange" means village, "magenta" means palace, and so on.

Additional data-embedding is possible, too, as long as your image is transparent. The opacity of each pixel can be used to specify some other physical properties of the terrain, such as temperature, humidity, etc. Or it may be used for metadata, in which the game's trigger zones, waypoints, and spawn hotspots can be encoded.

With this image-based map generation system, you can even manipulate the terrain while playing the game because it is just a matter of image processing (run by fragment shaders). The overall erosion of the terrain is the same thing as blurring the image, and hitting the terrain with a meteorite is the same thing as painting the impact zone with a semi-transparent black brush.

Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service