Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 8, 2023

When designing an indie game as a solo developer or a member of an extremely small team (e.g. only 2 or 3 people), one often faces a major dilemma which can be described as a chicken-or-the-egg problem. It is a tricky riddle to solve, perhaps trickier than most of the technical problems we encounter every day due to the multidisciplinary nature of game development.

The dilemma begins like this:

Suppose that you are a solo game developer who is trying to design and implement an entire game from scratch. There are typically two different approaches you can take to pursue this mission, which I will show below.

(Method 1): Start with the mechanics

You may choose to start your game development journey by first constructing the game's mechanics in order to come up with a solid prototype (i.e. a proof that your game has a potential to succeed). This solution is engineer-friendly, as it allows you to build the skeleton of the game in a highly system-oriented manner.

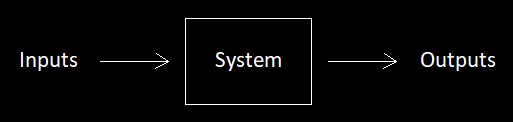

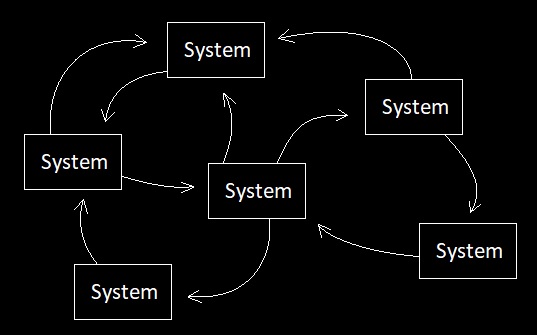

In this design philosophy, everything that the player will ever experience can be described as a network of systems, and each system is nothing more than a set of strictly mathematical relations between its inputs and outputs.

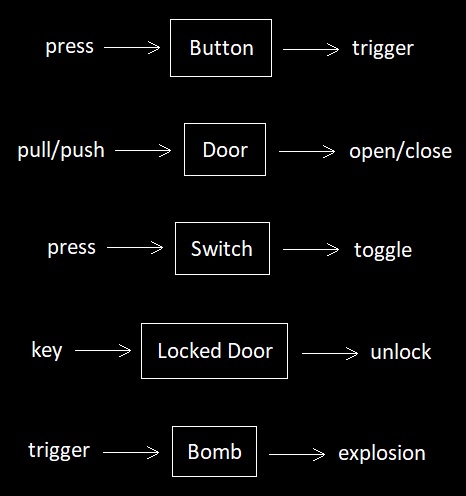

It is oftentimes convenient to design systems as tangible objects. For example, a button is a system because it emits a signal whenever somebody presses it. Here, the act of pressing the button is the system's input and the ensuing signal is the system's output.

In this manner, you may devise quite a multitude of systems which are represented by various interactible objects such as "door", "switch", "light", "platform", "cable", "elevator", "sensor", and so on. Once you fully specify their causal relations, it will be easy for you to join them together to give birth to all sorts of interesting emergent phenomena.

However, this approach soon falls short unless all you want to do is create a purely mechanical sandbox, since a mere assembly of such systems does not necessarily motivate the player to engage him/herself in the game. It is definitely possible to alleviate this problem by simply trying out a huge number of random mixtures among the elements you have made and then cherry-picking only the ones that are sufficiently entertaining, yet this is more or less just a bandage fix rather than a real solution.

It is also possible to attempt to prevent the limitations of your purely mechanical design by introducing systems that are intrinsically motivating. For instance, an enemy character is a system which automatically encourages the player to take a certain set of actions, regardless of where it is placed within the vast network of systems. This will ensure that the player will at least be driven to fight off the enemies no matter how the whole level is designed. Even this kind of solution, however, is not so sustainable because its long-term usage introduces too much repetition to one's gameplay experience and makes the player get tired too easily.

(Method 2): Start with the narratives

Alternatively, you may also begin your journey by constructing the narratives of the game first. Worldbuilding, storytelling, and kindred other means of structuring the game's narrative space are part of this methodology. Unlike the previous method which focused on the dynamics of systems and their causal dependencies, this alternate approach focuses on the set of purposes (volitional elements) and how they are related to one another.

Since everything in the game can be fictional, it is okay for a person to start by simply conceiving an empty world and populating it with a variety of elements such as characters, items, places, and so forth. One can then establish relationships among these elements based upon their inherent characteristics, and proceed to plot their ensuing actions on a timeline in order to formulate a story out of them.

This kind of imaginative endeavor lets the designer keep expanding the game's semantic context, not based on the mechanical aspects of gameplay but rather on its causal fabric of meaning.

Once you come up with characters and their own mental traits such as habits, beliefs, and desires, you will be able to tell what the reactions of these characters are likely to be when they are put under specific scenarios. With this in mind, you will be able to interpolate most of the details of your fictional world by means of induction.

This narrative-driven method, however, reveals its own limitations when it comes to actually implementing the game. A story, for instance, does not automatically fit the interactive nature of gameplay and therefore must be somehow "translated" into a form which makes sense to most gamers. Simply developing a highly story-driven game which forces the player to go through a strictly linear sequence of missions is one valid option to mitigate this, yet such a game is hardly replayable after its initial playthrough unless the gamer is a fan of speedrunning competition.

Unless the story itself is incredibly compelling, therefore, it is usually wise for one to make sure that the underlying narratives of the game world are somewhat compatible with the nonlinear dynamics of gameplay. And this becomes hardly achievable when the designer fails to keep gameplay mechanics in mind when devising the structure of the fictional world and its storyline.

(Problem): Lack of harmony between mechanics and narratives

A major takeaway from the aforementioned two methodologies is that both of them are prone to cause a great split between the two pillars of game development - mechanics and narratives. If we start constructing the game out of the former, we will have a hard time formulating the latter which fits the former. And if we start constructing the game out of the latter, we will have a hard time formulating the former which fits the latter. Our line of reasoning then leads to the third way which is shown below.

(Solution): Start with "mechanical narratives"

If we suppose that a game is made out of basic building blocks, the conclusion we are likely to reach is that such fundamental units of assembly ought to be imbued with the properties of both mechanics and narratives for the sake of integrating both of them into the heart of the game. Otherwise, we will either have to figure out how to define each narrative in terms of a composition of mechanics, or how to define each mechanic in terms of a composition of narratives.

Such multidisciplinary building blocks could be referred to as "mechanical narratives", as they are both mechanical and narrative in nature.

The real challenge of doing this lies on the process of coming up with such intricate fragments of meaning. And my intuition leads me to postulate that the best way to discover them is to identify the most atomic (i.e. indivisible) constituents of the science of life which reside somewhere between the study of biology and the study of psychology.

The reason behind this is that, once a person understands the nature of life, he/she will be able to control the behavior of whichever lifeform the game happens to interact with (aka "player"). This notion applies not only to games, but also other types of media such as books, movies, songs, electronic gadgets, home appliances, and the like.

A major problem we are facing here, though, is that life is such an inexplicably complex phenomenon that we find it nearly impossible to fully depict it in terms of theoretical elements. The thing is, however, that we do not really have to.

The RGB (Red-Green-Blue) color format does not cover the entire spectrum of colors which are recognizable by the human eye, yet it is being used universally as the basis of colors due to the fact that its coverage is satisfactorily broad. Likewise, we do not have to define every single nitpicky detail of life in order to establish a theoretical model of it in a manner that is as sufficiently general as to be considered "universal".

Let us try not to plunge into the endless rabbit hole of rigorous academic studies, and simply focus on the basics of what qualifies a physical object as a "living thing". Here is the question - Why on earth do we say that some objects are animate, while others are inanimate?

First of all, presence of causal relations among physical events does not necessarily distinguish animate objects from those which are inanimate because every physical entity possesses its own rules of interaction with respect to the rest of the world. When a box drops on top of a spring, the spring pushes it upwards to maintain its equilibrium. And when a ball drops on top of a ramp, the ramp lets the ball roll down its angled surface. These are all causal relations.

One might fancy that lifeforms can be distinguished from inanimate objects due to their possession of mental traits such as beliefs, desires, and emotions, yet the legitimacy of this argument is highly questionable.

For example, one can imagine that a mechanical spring "believes" that it must always endeavor to preserve its state of equilibrium (i.e. not being too compressed or too stretched), and that it "desires" to fulfill such a belief by means of an opposing force whenever an external event causes it to be either compressed or stretched. How can we tell for sure that a human being is something more than just an extremely sophisticated spring, despite the notion that one's mind may ultimately be able to be interpreted as a list of purely mechanical relations?

Yet, here is a point to consider.

Do we really have to make a strict distinction between things that are "living" and things that are "not living"? Can't we simply assume, for now, that the idea of life is just a human construct rather than a fundamental part of our reality? It doesn't really make that much of a difference from a game developer's point of view, does it?

Even if we consider the player as a mere mechanical contrivance which shows a happy face whenever it is triggered by a particular sequence of stimuli, the end result is not likely to differ too much from a case in which it is supposed that the player as a real human being.

What is important from a pragmatic point of view is the identification of types of elements which optimally contribute to player engagement, in ways which are quantitatively measurable such as the frequency of ad impressions and/or in-app purchases, time spent during each gameplay session, and so forth. The most difficult question lies on the matter of discovering such types as well as composing them in an elegant fashion, and this is usually considered an open-ended inquiry due to the reason that it depends on countless factors such as different kinds of potential audiences, game genres, market niches, and so on.

Those who understand the virtue of abstraction, however, will accord with my train of logic that such open-endedness is mostly due to the fact that many game developers are highly sensation-oriented by heart, that their domain of intellect hardly stretches itself beyond that of mere case-by-case analysis. Their argument usually proceeds like this: "A videogame is such a complex piece of art, that one cannot possibly break it down into a few clever math equations as though it is some kind of hard science."

If we are obliged to take such reasoning seriously, then, we will not be able to even dare to suggest a rational model of our economy, finance, psychological phenomena, biological phenomena, and many other intricate systems of the world in which we live, simply due to the personal feeling that they are "too complex". Why bother to formulate all sorts of fancy graphs and pie charts to analyze the stock market? Why bother to conduct all sorts of psychological experiments to analyze a patient's mind?

When it comes to scientific reasoning, any decent thinker can be assumed to be humble enough to acknowledge that we cannot expect ourselves to be able to instantly grasp the full picture of whichever subject is under our scope of research. Yes - a person's brain is complex; our economy is complex; a living organism is complex. So what? Does it mean that nobody should even dare to approach any of these subjects from a rational standpoint, and that we should just all smoke weed and chill?

Of course we cannot comprehend everything in advance, and this is precisely the reason why scientists study the totality of our nature by investigating small fractions of it one at a time, based upon specific experiments that are performed under strictly controlled scenarios. This is what I would refer to as a "modern" approach to mysteries which surround us, as opposed to mere superstition which propels us to remain content with a mud pool of wishful thinking.

Games are not so different from other sciences in this regard. Some people may claim that this statement is so blatantly close-minded because a game is a "creative endeavor" or an "art form" and has nothing to do with science, yet an independent thinker who is endowed with an interdisciplinary taste of reasoning is likely to agree that such wordplay is so frustratingly naive, that it is not even worth the effort to prove why it hardly means anything significant from a holistic point of view.

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service