Author: Youngjin Kang Date: February 8, 2025

Sandwich Engineering is a truly multifaceted area of study. It contains its own grammar, semantics, and procedures, as well as real-life examples (such as the factory analogy we have seen recently).

When it comes to pragmatic considerations, however, we should not forget that we need to spend resources in order to make a sandwich.

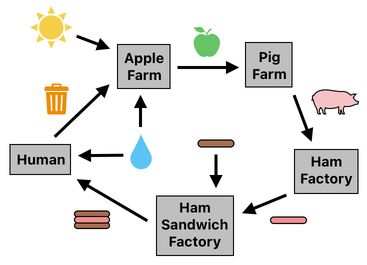

For instance, we cannot summon the ingredients of a ham sandwich out of thin air; the ham will have to come from a pig, the pig will have to come from the food it has eaten, and the food will have to come from crops which were grown somewhere else, and so on.

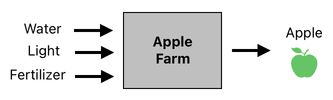

Every process, including the making of a sandwich, absorbs resources and converts them into other types of resources. For example, an apple farm takes resources which are necessary for sustaining plant life (e.g. water, light, and fertilizer), and grows apples off of them.

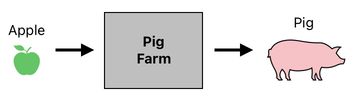

A pig farm, in turn, raises pigs by nourishing them with these apples.

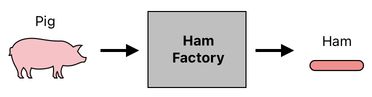

Pigs, once grown, go to the nearest ham factory and transform themselves into slices of ham.

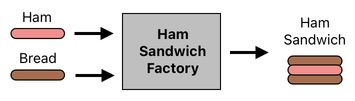

These slices of ham, then, travel to the nearest ham sandwich factory, enclose themselves with pieces of bread, and morph into ham sandwiches.

So, here is the idea. Resources do not come from nowhere; they must originate from somewhere else. And as we trace their origins, we begin to realize that there is not really a single "ultimate origin" before which no preceding cause can be found.

Resources neither get created nor destroyed. They circulate in our closed environment, continually dying and reviving in one form or another.

The world is one grand cycle of resources, which recurrently undergo a sequence of changes as they transition from one system to another.

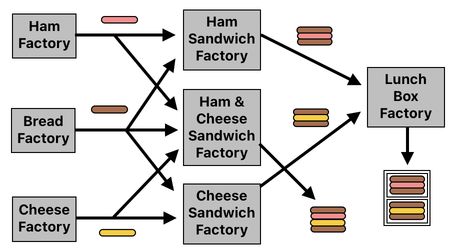

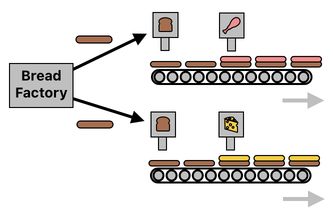

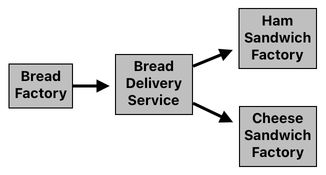

Such a cycle, of course, is made up of myriad intertwined pathways, where streams of resources either converge or diverge as needed. A single producer may distribute its resources over multiple destinations, and a single destination may receive resources from multiple producers. An example is shown below.

There is one thing which may feel a bit vague, though. In the diagram above, for example, the branching pattern of arrows indicates that the bread factory is distributing its bread over 3 separate places - a "ham sandwich factory", a "cheese sandwich factory", and a "ham & cheese sandwich factory".

For the sake of simplicity, let me just omit the "ham & cheese sandwich factory" from the scene for now and leave only the other two.

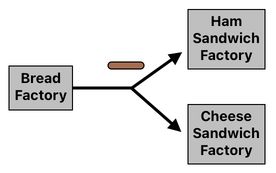

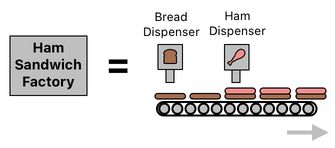

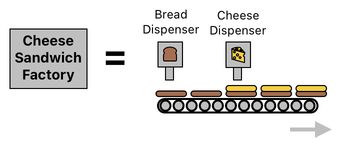

We can imagine that the "ham sandwich factory" uses a bread dispenser for adding pieces of bread to its own production line.

The "cheese sandwich factory", too, can be imagined to be utilizing its own bread dispenser for adding pieces of bread to its own production line.

What seems so obvious here is that a bread dispenser is not a "magic hat" from which an infinite number of bread pieces can spawn. They must come from somewhere, and, in our case, this "somewhere" is the bread factory which functions as a bread-supplier.

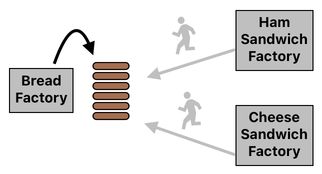

Here is something fishy. Suppose that this bread factory continuously generates pieces of bread and puts them in its own storage area. What shall we do, then, to distribute them over their appropriate consumers? Should the employees of the sandwich factories come over, grab these lingering pieces of bread, and carry them back to refill the bread dispensers?

Such an approach may not sound too bad, but let us remind ourselves that bread is not the only type of ingredient that a sandwich needs. A ham sandwich factory, for instance, demands a continuous inflow of both bread AND ham in order to be able to produce ham sandwiches. Should its employees, then, repeatedly visit both a bread factory AND a ham factory just to provide their production line with the necessary ingredients?

This is not something we would desire. We want a central delivery system which is specialized for the work of transportation, so that the factory workers won't have to take extra time moving their resources from place to place.

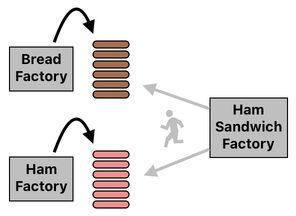

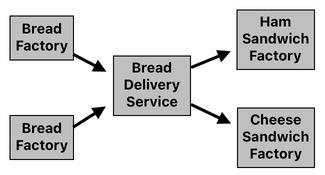

One of the major benefits of having such a "middleman" is that it swiftly handles the case of multiple suppliers. If there are two distinct bread factories (as shown below), for example, sandwich factories will be able to receive bread even if one of these suppliers fail to operate.

The presence of such a network of systems, however, is complex enough to annoy people who are not so fond of systematic thinking. Just take a look at the diagrams above; although I have only been dealing with a couple of simple cases, you can already tell that they are being bloated with a bunch of arrows, boxes, and other technical pieces.

Fortunately, it is not always necessary for us to represent everything in terms of a fabric of interrelated modules. Sometimes, it makes more sense to just come up with a single "universal" system which is so functionally versatile, that it is capable of handling a broad range of tasks as long as it is given an appropriate list of instructions.

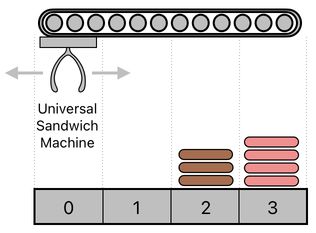

For the purpose of demonstrating such a concept, let me introduce a new, powerful piece of machinery called the "universal sandwich machine".

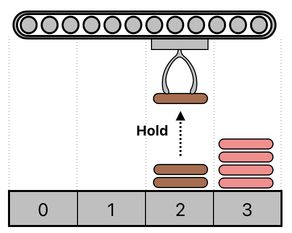

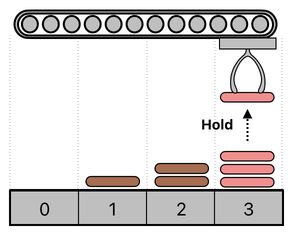

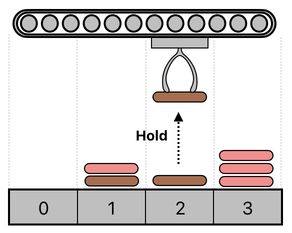

This machine works in a manner similar to that of the "holder" module I've shown before. In addition, however, it is capable of jumping from one place to another. Also, it does not operate on a conveyor belt upon which the items are moving at a constant rate; instead, it hovers above a static table and visits each of its discrete locations whenever necessary.

In the picture above, for instance, there are 4 distinct slots on the table called "0", "1", "2", and "3". The universal sandwich machine begins its journey at "0".

Let us say that the goal of this machine is to make a ham sandwich. What shall it do, if we want it to fulfill such an objective?

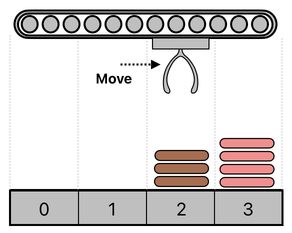

First, it needs to lay down the bottom piece of bread. To do that, it ought to move to the place in which a piece of bread is available.

The next step, of course, is to grab a piece of bread that is right underneath.

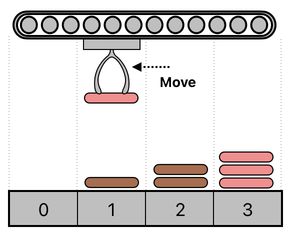

The question is, at which specific location do we want to install our ham sandwich? It really depends on the context, but for the sake of illusration, let me just suppose here that we would like to see a ham sandwich at position "1".

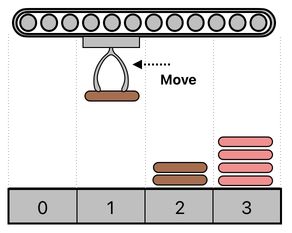

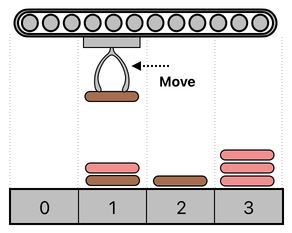

The machine, then, will need to bring its piece of bread to position "1",

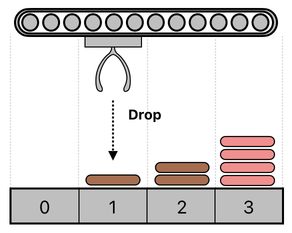

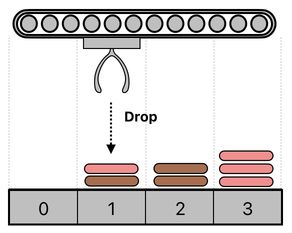

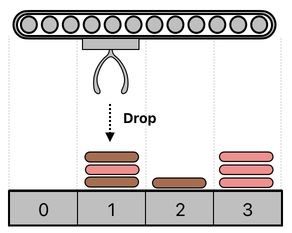

... and then drop the piece of bread it has been holding.

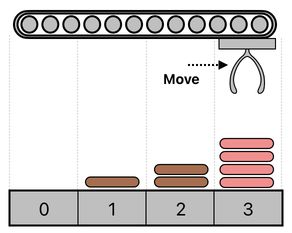

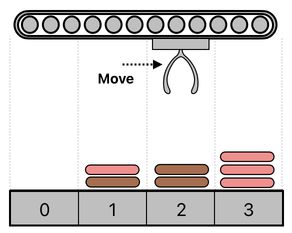

Now that the bottom piece of bread is prepared, the machine will then proceed to move to the place from which it is able to fetch a slice of ham.

Then, just like it did previously, it will grab whatever is underneath its current spot.

The next step is to move back to position "1" (where the ham sandwich is being prepared),

... and then drop the slice of ham it has been holding (just like it did with the piece of bread).

Now, the only remaining ingredient is the top piece of bread. Grabbing one and putting it on top of the slice of ham will close up the upper portion of the sandwich and turn it into a fully legitimate "ham sandwich".

The next immediate step for fulfilling such a process, of course, is to move back to the stock of bread pieces.

The machine will then grab a piece of bread, move back to where the ham sandwich's position, and drop the piece of bread to complete the full sandwich-making process.

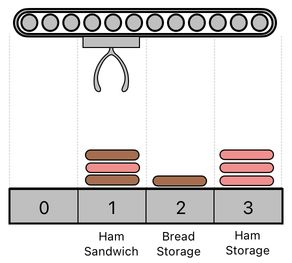

Now we have it! If you take a look at position "1", you will see that it is now occupied by a ham sandwich. We did not employ a complex network of conveyor belts and dispensers to manufacture a sandwich. All we needed to do is prepare a special kind of device called the "universal sandwich machine" and let it carry out an appropriate list of instructions.

What is shown below is the list of instructions that the machine just carried out.

moveTo 2

hold

moveTo 1

drop

moveTo 3

hold

moveTo 1

drop

moveTo 2

hold

moveTo 1

dropHowever, it is also true that even such a universal machine is incapable of summoning resources out of nowhere; it must fetch the necessary ingredients from somewhere else, which is the reason why it had to have access to a stack of bread (i.e. position "2") as well as a stack of ham (i.e. position "3").

This is not the end of the story.

For example, imagine that we decide to create multiple copies of this "universal sandwich machine" and let them cooperate as a team. One of them might be designed to bring pieces of bread from outside and store them at "2", while another might be designed to bring slices of ham from outside and store them at "3". Meanwhile, another machine might be instructed to pack the finished ham sandwiches and put them into cardboard boxes, and so on.

This is "division of labor" in action.

(End of "Sandwich Engineering")

Previous Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service