Author: Youngjin Kang Date: January 30, 2025

When building a sandwich from scratch, however, we often face moments of ambiguity which could be a bit annoying. And if you really want to become a master of sandwich engineering, you should understand the nature of such moments as well as how to treat them properly.

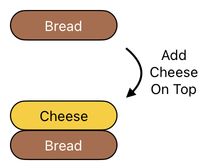

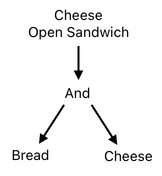

Let me give you an example. In the previous chapter, I have shown you that putting a slice of cheese on top of a single piece of bread will turn it into a "cheese open sandwich".

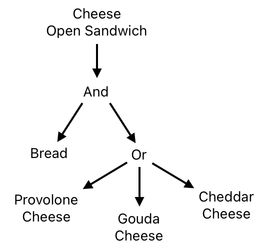

There is a great deal of uncertainty going on here, though. What kind of cheese do we refer to exactly, when we say: "cheese open sandwich"? There are different types of cheese, and we will never know which one we are talking about as long as we just say "cheese".

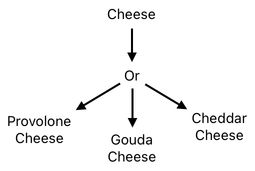

For instance, suppose that there are 3 types of cheese available - Provolone, Gouda, and Cheddar. This will imply that whenever we say the word "cheese", we are indicating one of these 3 types (not all of them, but one).

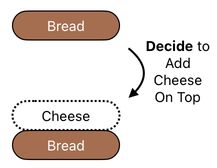

This means that we cannot just put "cheese" on top of a piece of bread, without specifying its type. "Cheese" is an abstract concept. It is not a tangible object which we can touch, smell, or eat. Rather, it is a general category of things which can be classified as "cheese".

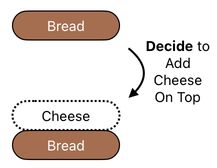

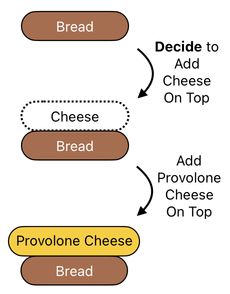

Thus, whenever we are using the word "cheese", we are merely "deciding" to put a slice of cheese to the sandwich without actually doing it (since we haven't yet determined whether this cheese should refer to Provolone, Gouda, or Cheddar).

And of course, we are free to cancel our decision if we want to.

Since "cheese" is an abstract concept, we must be able to tell that a "cheese open sandwich" is an abstract concept, too. So for example, when we say "cheese open sandwich", we know that it must be made of bread and cheese, right?

But the problem is that the cheese itself is something ambiguous; the word "cheese" alone does not tell us exactly which kind of cheese it is. Thus, the "cheese" part of this sandwich must comprise a number of alternative options (i.e. Provolone, Gouda, or Cheddar).

This sandwich is abstract (i.e. not tangible) because we have not fully specified its ingredients yet. As long as there is room for ambiguity, it cannot exist in real life.

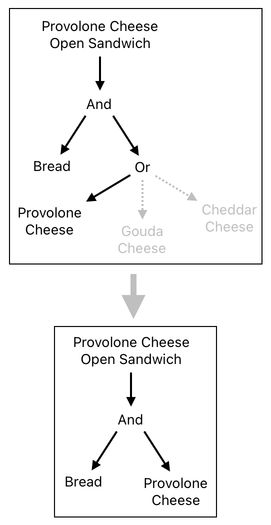

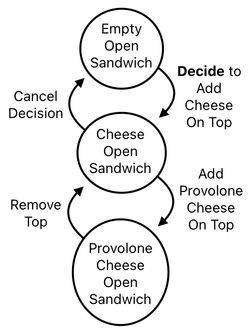

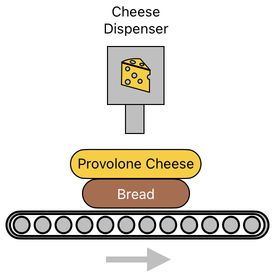

It is only after we make specific choices to resolve all the ambiguities, that the sandwich will finally become tangible. In the example below, I chose to put a slice of Provolone cheese on top of the bread. This cleared out every bit of indeterminacy from the sandwich and turned it into something solid (i.e. non-abstract).

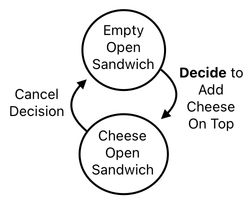

We can summarize the steps we have taken so far as a harmony between two types of actions - one for presenting ourselves with a set of choices, and the other one for actually making a choice out of them.

Putting a slice of Provolone cheese on top of the bread, for instance, required me to first "decide" to put a slice of cheese (which gave me access to 3 choices - Provolone, Gouda, and Cheddar), and then pick the choice called "Provolone".

And of course, these two steps are both reversible, meaning that I am able to remove the cheese from the top and turn the whole thing back to an "empty open sandwich".

A sense of confusion may arise here, though. What do we mean when we say that we "decided" to put a slice of cheese?

Whenever we "decide" to do something, we are not actually doing it. Instead, we are simply making a promise to do it in the future. This is more of a mental phenomenon, rather than something which is physically measurable. However, it is still feasible to express such a sense of promise by physical means.

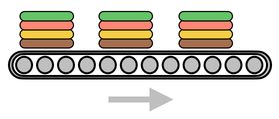

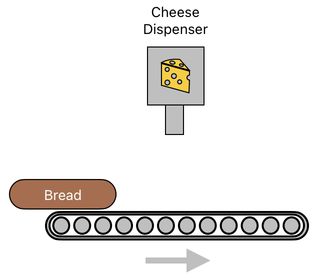

Imagine that we are operating a "sandwich production line" inside a factory. There is a conveyor belt which carries stacks of sandwich ingredients. By the time they reach the end of the belt, they will transform into fully legitimate sandwiches.

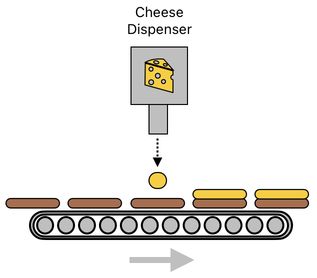

Oh, but we cannot make stacks of ingredients just by carrying them on a conveyor belt. We need dispensers which will put new ingredients on top of the existing ones. In order to let our sandwiches have cheese in them, for example, we need a cheese dispenser.

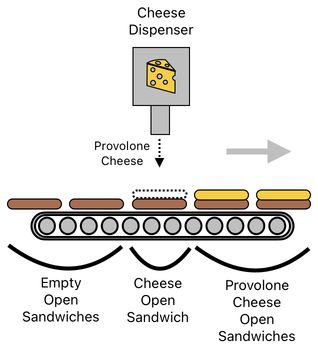

As you can see, this cheese dispenser will be responsible for dropping cheese on top of bare pieces of bread that are passing by, thereby turning them into "cheese open sandwiches".

Let us suppose that a single piece of bread happened to enter the conveyor belt, above which a cheese dispenser is situated. At first, this piece of bread is obviously just an "empty open sandwich" because it is just a single piece of bread.

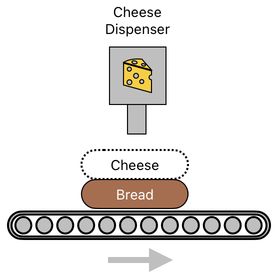

The moment it comes right beneath the cheese dispenser, however, it becomes a different story. Here, we know that a slice of cheese is about to be dropped on top of the piece of bread. We are not yet sure exactly what kind of cheese will come out of the dispenser, but we can at least assure that "some" cheese will come out it.

This is the very moment at which we can sense a "promise" of having a slice of cheese on top of the bread. At this point in time, therefore, this particular piece of bread should be considered a "cheese open sandwich". Although it does not have an actual slice of cheese on it yet, we know that it is about to have one soon.

And as soon as the dispenser drops an actual slice of cheese (such as Provolone), this thing called "cheese open sandwich" will transform into something tangible - that is, something which has real cheese on it (not an abstract kind of cheese).

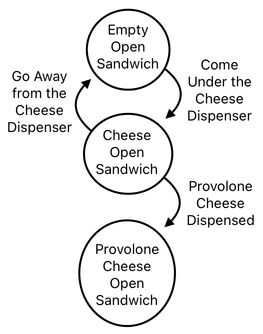

We can map this out as a diagram, like the one shown below. A single piece of bread (aka "empty open sandwich") turns into a "cheese open sandwich" as soon as it becomes clear that a slice of cheese is about to drop on top of it, and subsequently turns into a "provolone cheese sandwich" as soon as it receives an actual slice of Provolone cheese.

And when you look at the conveyor belt as a whole, you will realize that the queue of sandwiches which continuously flow from the left to the right are undergoing a series of transformations one by one, depending on whether each of them is coming toward the cheese dispenser, going away from the cheese dispenser, or is passing right underneath it.

In a way, therefore, a conveyor belt can be thought of as a "sandwich transformer". It absorbs an incoming stream of sandwiches, transforms them one by one, and pours them out as an outgoing stream of sandwiches.

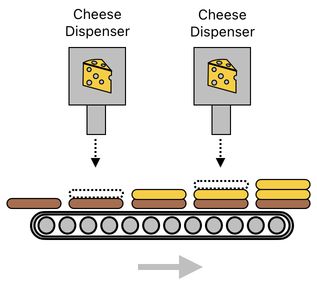

We can keep expanding this idea indefinitely. By adding yet another cheese dispenser to the belt, for example, we are able to manufacture not just single-cheese open sandwiches, but also double-cheese open sandwiches (see the image below).

What's next? Oh well, it is not so hard to imagine the sheer variety of opportunities waiting before us. We may as well introduce a "bread dispenser" and "ham dispenser" to produce "ham sandwiches", or a "bacon dispenser" to produce "bacon sandwiches", and so on.

The horizon of possibilities is endless.

(Will be continued in Chapter 6)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service