Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 29, 2023

(Continued from volume 7)

Interpreting our ideas as relations is a pretty neat way of making sense of the world around us. However, it also compels us to ask ourselves whether it is absolutely necessary to separate ideas into two distinct categories called "relations" and "non-relations".

We should note that there is another question which must be taken into consideration. It is the question of whether there is any idea which is incapable of being considered a relation.

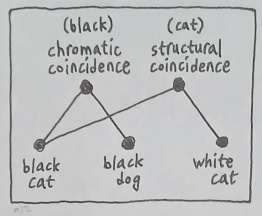

In the previous example, we saw that the idea "black" could be defined as a chromatic coincidence between "black cat" and "black dog". It is not hard to imagine that, in a similar fashion, the idea "cat" could be defined as a structural coincidence between "black cat" and "white cat" because these two are sufficiently close to each other in their morphological feature space.

What about the parameters of the aforementioned relations, such as "black cat", "white cat", etc? Are they just standalone units of perception which cannot be described in terms of ways in which they function as semantic binding points?

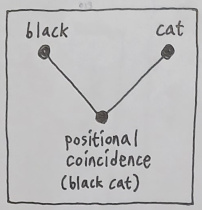

Let us consider "black cat" for example. When I see an amorphous patch of blackness before me, I just call it "black" without mentioning the word "cat" because I do not perceive in this patch any form which can be identified as a cat. Likewise, when I see the shape of a cat before me which does not have any particular color in it, I just call it "cat" without mentioning the word "black" because I do not perceive any blackness in this shape.

And the reason why neither of the two cases shown here can be termed "black cat" is straightforward; neither of them attaches "black" and "cat" to the same physical location, which is proven by the fact that it is possible for me to look at one of them without looking at the other. This allows me to say that "black cat" is a positional coincidence between "black" and "cat".

And the major takeaway from this is that there seems to be nothing which stops us from fancying that every idea is a relation, and that every relation can be depicted in terms of other relations (e.g. coincidences).

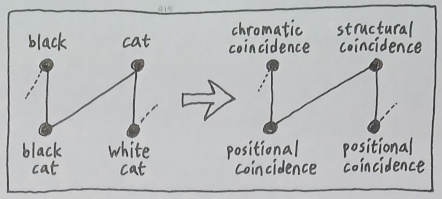

What makes it possible to freely translate from one layer of abstraction to another, according to the observation we have been making, is the availability of different categories of coincidence. Chromatic and structural coincidences give birth to the process of generalization which is based upon chromatic/structural proximity, and positional coincidences give birth to the process of specification which is based upon locational proximity.

This is obviously not the end of the story, though. I still haven't explained the reason why there are apparently multiple kinds of coincidences, nor have I made any endeavor whatsoever to analyze their conceptual details.

A couple of thought experiments are necessary to investigate this problem. Let us first assume that there is only one object called "black cat" somewhere in an empty space. And let us also assume that I am a bodiless spectator whose range of observation is confined to this empty space. In this particular context, no matter where I look at, the only two options I have is: (1) To see both "black" and "cat" simultaneously at a given moment, or (2) To see neither "black" nor "cat" at a given moment.

The reason why this constraint holds is that, under the condition stated above, the idea of "black" and the idea of "cat" are both anchored to the same spot in physical space, which makes it impossible for me to observe one of them without observing the other. This is the quantitative definition of "positional coincidence".

Other types of coincidence should share the same mechanistic root. In the case of chromatic coincidence, the empty space I illustrated above may be composed of color dimensions such as R (Red), G (Green), and B (Blue) instead of the usual spatial dimensions such as X, Y, and Z. In the case of structural coincidence, it may be composed of morphological dimensions such as length, compactness, surface area, and so forth.

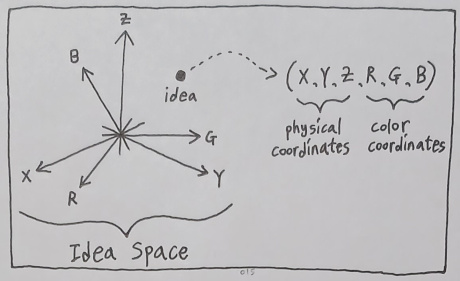

In this regard, we might as well claim that a coincidence essentially means a collision between a pair of entities in a hypothetical coordinate system, which is a subspace of the universal continuum of ideas (i.e. "idea space").

It is not difficult to imagine that the idea space is the ultimate collection of every idea we can ever manage to conceive. If we just suppose for a moment that this space only consists of two independent aspects of qualia called "position" and "color", we will be able to assert that every idea is a piece of data which contains two properties in it - position and color.

And if we proceed to say that a position is a 3D vector (denoted by X,Y,Z) and a color is also a 3D vector (denoted by R,G,B), it will automatically suggest that an idea is a set of coordinate value specifications inside a 6-dimensional model of the idea space, wherein the first 3 components indicate its physical dimensions and the last 3 indicate its color dimensions.

If all 6 of these coordinate values are specified, the idea will be a point. If only 5 of them are specified and others are left unbounded, it will be a line. If only 4 of them are specified and others are left unbounded, it will be a plane, and so forth.

(Will be continued in volume 9)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service