Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 22, 2023

(Continued from volume 5)

One's search for reality usually begins with the problem of abstracting out our worldly sensations for the purpose of approaching the unified essence which is hidden behind the apparent chaos we face every day.

There are so many things happening before us at every moment, and it takes a substantial degree of theism to suppose that there is a supreme order which encompasses the ultimate ensemble of what we can sense and reason with. Even the most reductionist of all sciences is not exempt from this, as it still presumes that the universe is being governed by a law which dictates that almost every form of complexity is reducible to simpler ones.

And the usual conjecture of ours is that the more abstract our context of reasoning becomes, the more accurately we will be able to embrace the nature of such a law. The primary reason behind this is that the total number of generic ideas is far smaller than that of specific ideas. Fewer things are usually easier to handle than many.

Yet, we should be aware that there are different methods through which the course of abstraction can be carried out. In the previous volume, I demonstrated the problem of groundless abstraction which evinced a tendency to immure itself in its own tiny cell of contextual independence - a minimalist's badge of intellectual superiority which ignites the heart of pure mathematicians with a subtle kind of fervor, yet never quite sympathizes with the tides of everyday life.

If we begin our train of thoughts with the most minimal fragments of qualia we can possibly express in our language, such as numbers, vectors, sets, algebraic symbols, operators, and the like, we will indeed be able to construct an isolated playground of reason in which we have the freedom to commit whichever genre of conceptual masturbation we desire.

Such a self-made prison of thoughts, however, is so intrinsically disconnected from our immediate senses, that it presents us with an exceptional challenge when it comes to laying down a semantic bridge between itself and the rest of the world.

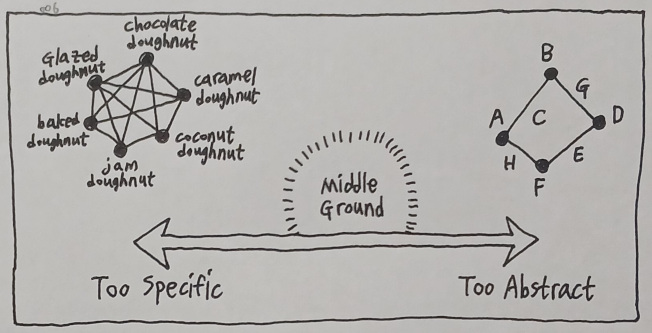

But then, of course, we cannot abandon the necessity of mathematical simplification altogether because otherwise we will soon be lost amidst a vast field of infinite possibilities. This leads to the conviction that the key lies somewhere between free association and pure abstraction.

How to draw the landscape of this middle ground is yet another problem to solve. Fortunately, there is one major tool which comes in handy - generalization.

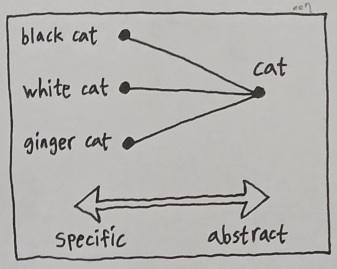

Take a black cat as an example. This lovely creature can be represented as an idea because we are able to think about it. Furthermore, it makes sense to state that there are other kinds of cats as well, such as white cats, ginger cats, Siamese cats, Persian cats, and etc.

These cats have one commonality in them in the sense that every one of them belongs to the particular class of feline beings which is typified by the word "cat", and a succinct way of expressing such a concept is to associate all these subspecies with the single binding point called "cat".

Here, we are able to witness that the degree of abstraction deeply correlates with the topology of associations. The more an idea associates itself with others, the more abstract it becomes due to the notion that it functions as a means of convergence by which those with shared traits are taxonomically grouped together.

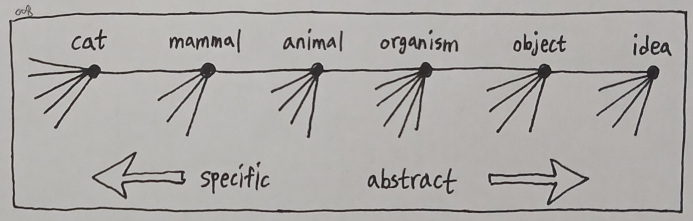

Such a method of genericizing concrete ideas into more general ones suggests us that we can keep building layers upon layers of abstraction this way. For instance, a cat is one of many types of mammals, a mammal is one of many types of animals, and an animal is one of many types of organisms. An organism is one of many types of objects, and an object is one of many types of ideas we can ever conceive.

This cascade of reason then guides us to model our universe as one gigantic hierarchy of beings, which is basically a tree of nodes from a computational standpoint. The closer you get to its leaves, the more specific your ideas will be. The closer you get to its root, the more generic your ideas will be.

And the benefit of this classification-oriented formulation is that, unlike free association which is prone to conjure a great deal of chaos, it retains some kind of directionality in the way in which ideas are being associated. What we are seeing here is a nicely streamlined branching pattern, rather than a helplessly intertwined hairball of connections.

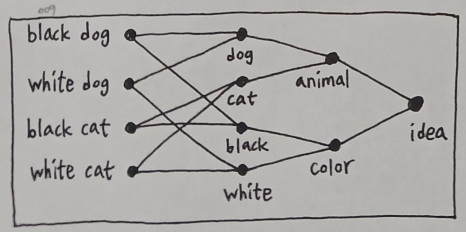

One must not be so quick to conclude that the whole of our reality is required to be summarized as a tree, though, since there are reasons to say that each idea could be explicated in terms of not just inheritance but also composition.

Let us imagine that there are four ideas which are called "black dog", "white dog", "black cat", and "white cat" respectively. It is not difficult to understand that "black dog" and "white dog" can both be associated with the idea of "dog", and that "black cat" and "white cat" can both be associated with the idea of "cat". This creates a level of abstraction which groups four ideas into two.

A slightly different angle of view, however, tells us that it is also possible to group these four ideas by their chromatic attributes. For example, "black dog" and "black cat" can both be associated with the idea of "black", whereas "white dog" and "white cat" can both be associated with the idea of "white".

And both of the aforementioned interpretations are valid as far as our usual habit of cognition goes, which subsequently makes it reasonable to let them simply coexist, thereby suggesting that a series connection of bipartite graphs should probably portray the map of our reality in a more accurate manner.

(Will be continued in volume 7)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service