Author: Youngjin Kang Date: October 19, 2023

(Continued from volume 4)

It has hitherto been suggested that the most minimal language which needs to be exhibited in order to let us build a model of reality comprises two fundamental units of existence; one is called "ideas", and the other one is called "associations". And we also saw that the syntactic possibility space which they allow us to traverse is prone to sprout a vivid conviction which tells us that it closely resembles that of graph theory.

The major trouble we are forced to confront at this point is that it is not so straightforward to determine the most optimal direction of intellectual exploration we ought to pursue when we are only given such a tiny set of building blocks to expand our context of reasoning.

To formulate this apprehension a bit more precisely, I would say that there is a dilemma between diversity and minimalism when it comes to approaching the nature of reality.

On the one hand, a person may begin the journey by simply identifying whatever pops up in one's mind as an idea, and then freely associating it with other randomly popped up ideas in a completely orderless manner.

An example of this is not so difficult to illustrate. Suppose that the idea of an old-fashioned American doughnut just crossed my mind. This makes me declare that "Old-fashioned American doughnut" is an idea which can be depicted as a single point. Subsequently, I realize that this particular type of doughnut shares close resemblance with other types of doughnuts, such as Krispy Kreme's original glazed doughnut, Safeway's blueberry-flavored doughnut in U District, Seattle, and countless others. For the sake of free association, I declare all such instances as individual ideas, and draw a near-infinite number of lines among every one of them because they all share similarities with one another due to the fact that they are all doughnuts. And- oh! By the way, I know a celebrity who likes doughnuts, so let's express this person as an idea and associate it with the aforementioned ideas, too, and so on.

If I keep allowing my stream of consciousness to lead me through this endless rabbit hole of seemingly random whims, I will soon find myself trapped inside a jungle of chaos, hardly capable of extracting any recognizable pattern from the hidden source of truth from which my thoughts are assumed to originate.

Alternatively, a person may as well choose to start one's analysis by only dealing with ideas which are purely abstract in the sense that they can only be represented in terms of mathematical symbols. Such ideas are akin to what vertices are in graph theory; they do not mean anything other than that they are arbitrary entities being defined within the context of the mathematical theory to which they belong.

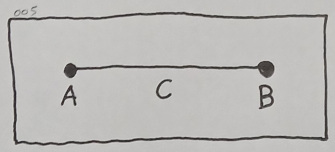

An example of this is just as easy to describe as that of the former. I may choose to declare two ideas called "A" and "B", and that these two are associated with each other under the name "C". This case is far simpler than the convoluted mess we witnessed before; here, we are able to safely analyze such an isolated body of imagination without having to constantly ask ourselves, "What if there is something else I am missing here?"

At least within the scope of this strictly limited context, the aforementioned components (i.e. A, B, and C) cover the entirety of what we are supposed to reason with; they collectively form a controlled environment, which is reminiscent of an isolated chamber inside a scientific laboratory.

This is indeed neat, and it rescues us from the pain of having to exhaustively search for all possible ways in which we can enumerate and arrange our thoughts for the sake of making sure that the collective sum of what we are reasoning with is fully disclosed and thorough. This method, however, comes with its own downside.

Suppose that I come up with a set of arbitrary symbols (such as A and B) and call them "ideas". I may also make a bunch of random associations among them, and label them with yet another set of arbitrary symbols. Then what? If I simply keep doing this and try to map out a whole spectrum of ways in which such entities can be composed, I will only enable myself to find out a list of emergent properties which are confined to the study of graphs, which is essentially nothing more than what math people have already done a million times in their natural habitat.

This is one of the curses of minimalistic abstraction. An a priori concept, seemingly untainted by any empirical relation, exercises its own dimension of infinite power by claiming its right to potentially mean anything, yet it never means anything specifically. Such a tenacious level of detachment from our worldly concerns makes it an inadequate means of propelling ourselves toward the direction of where truth is expected to be, since our everyday experiences do constitute part of our reality and therefore should be taken into account, no matter how superficial and distorted they might be when interpreted by our senses.

(Will be continued in volume 6)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service