Author: Youngjin Kang Date: November 5, 2023

(Continued from volume 10)

When we think of a network of ideas as a nested body of sets, what we are able to witness is that there is a strong parallel between itself and its functionally analogous representations.

First, I showed you that ideas and their respective relations could be illustrated as a graph in which each vertex denotes an idea and each edge denotes a relation between ideas.

Secondly, I came up with a more quantitatively satisfying model which characterized ideas as vectors in a hypothetical space (aka "feature space" or "conceptual space"), wherein each dimension carries its own distinct way of measuring our senses.

And by the end of the last volume, I hinted the feasibility of imagining that an idea is a set, which suggests that a relation can be depicted in terms of a set operator.

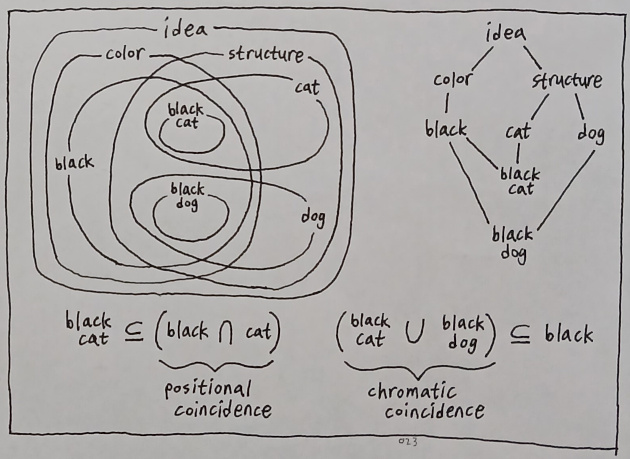

A precise description of this framework requires an example. Let us suppose that the "idea of idea" is the universal set which contains all other ideas. And Let us say that "color" and "structure" are two of its subsets.

We can keep expanding this thought experiment pretty easily. Since "black" is one of many chromatic subtypes, it is a subset of "color". Since "cat" is one of many structural subtypes, it is a subset of "structure". The list goes on.

Now here is something slightly trickier; what about "black cat"? At first the hierarchical impression of sets seems to prevent us from formulating such a synthetic idea, but a bit of intuition soon leads us to the conviction that a composition (i.e. positional coincidence) between two ideas can be found within their intersection.

Likewise, "black" can be defined as a chromatic coincidence between "black cat" and "black dog" based upon the premise that the union between "black cat" and "black dog" is a subset of "black".

In other words, one is able to say that the process of generalization (i.e. mapping of multiple specific ideas to one abstract idea) involves a union of sets, whereas the process of specification (i.e. mapping of multiple abstract ideas to one specific idea) involves an intersection of sets. Such a construct reveals its own analogy in boolean algebra as well, in which the logical OR (+) operator translates to generalization (i.e. identification of a common feature in multiple places) and the logical AND (x) operator translates to specification (i.e. composition of multiple features in one place).

So, what's the point of building and showcasing such an analogous model, which is not even much simpler than our previous vector-based system? And yes - this bit of skepticism is totally understandable, as it looks like all I did was simply reinterpret my format of discourse from analytical geometry to set theory.

However, one should also note that the set analogy provides us with a quite elucidating evidence that qualia do not have to be numerical in nature. Unlike dimensions and their coordinate axes, sets do not require numbers to signify their presence because they are symbolically defined.

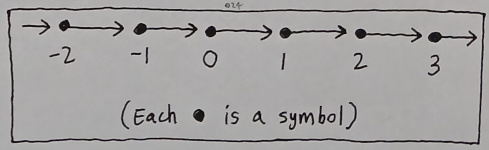

Fundamentally speaking, though, I do admit that numbers are symbols too. And the reason behind this is that a line of numbers can be fancied as a directed chain of symbols, each of which possesses only up to one incoming edge and one outgoing edge.

Such a chain may be referred to as a "dimension" as long as we assume that it endows us with a unique way of partitioning our fabric of thoughts.

One must be aware, however, of the fact that a sequence is just one of many possibilities. Once we have symbols in our intellectual playground, nothing prevents us from joining them in the manner of a generic graph in which there is a plethora of potential variances such as branches, loops, and so on.

So the general sentiment I have in regard to the necessity of numerical quantification is that of skepticism. At least from a technical perspective, a number line is nothing more than a special case of what we can do with symbols. And it is not so easy to divine a clue which imposes a decisive reason why we must prefer such a case over others.

A set-based model frees us from numerical reasoning at least, while its ontological basis is still quite artificial in the sense that it presumes the existence of arbitrary categories such as "black" and "cat".

It does indeed look like there is no external source of truth which dictates that our taxonomy of ideas must be taken for granted without presupposing some degree of subjectivity, yet I would still say that a set is closer to the heart of truth than a dimension because, at least, the language of sets does not limit the arrangement of symbols to a linear pattern.

The next question lies on the legitimacy of set-based thinking. Its underlying motivation is that, for the sake of exercising our faculty of reason, we must somehow come up with a method of classifying our thoughts, for otherwise we will be stuck in the eternal inactivity of universal oneness - the bodiless spirit of unity from which nothing differentiable arises.

(Will be continued in volume 12)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service