Author: Youngjin Kang Date: November 2, 2023

(Continued from volume 9)

From a holistic perspective, my faculty of reasoning suggests that our reality consists of discrete entities called "ideas", and that each idea is a vector which resides in the idea space. If there are N dimensions of qualia in total, this all-encompassing space will have to be made out of N dimensions.

It has so far been explained that the so-called "coincidences" among ideas are essentially just geometric operations happening in such a space, as well as that each of them is also capable of being carried out on a computational basis by means of numerical filters.

One might be tempted to continue expanding this stream of consciousness by asking questions such as: "What if we take the union of two ideas instead of their intersection?", "What if we measure the difference between two ideas and come up with their derivative?", and so forth.

However, the main objective of my writing is to discover the fundamental root of reality itself, rather than to keep digging its treasure cave of mathematical intricacies. Such intellectually stimulating details may indeed be of great use in practical scenarios (e.g. engineering), but they do not necessarily encourage us to approach the heart of our universe's divine order because they are based upon an arbitrary assumption which rather dogmatically claims that our ideas are made up of a set of hypothetical beings called "dimensions".

In order to seriously search for the origin of reality instead of falling into the trap of "Abstraction for abstraction's sake", we better stop concentrating too much on the existing theory's internal synthetic revelations and instead question the validity of the theory itself.

According to the model I have devised so far, reality is defined in terms of ideas and each idea is defined in terms of dimensions. If we desire to confirm that this sort of conception is reasonable, therefore, we must be able to assure that a dimension really is an irreplaceable part of our ontology.

What is a "dimension", anyways? From a pragmatic point of view, one may say that we use dimensions to differentiate one thing from another. The presence of a dimension called X, for example, lets us tell that point (X = 0) is different from point (X = 1) because they do not coincide in dimension X. In other words, the notion of "difference" is what necessitates the introduction of dimensions in our faculty of logic.

Besides, it is the reason why we have the concept of numbers in the first place; we use a number to indicate a distinct mode of perception. Since we typically imagine that there are different types of qualia which do not mix up with one another (e.g. length, duration, weight, brightness, loudness, etc), such a number usually belongs to one of many independent dimensions.

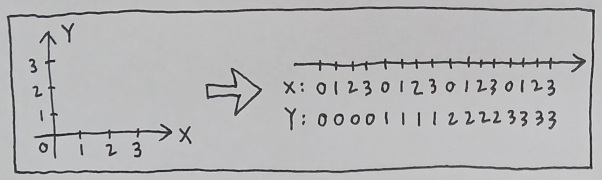

From a purely functional view, though, one cannot simply resist the urge to suggest that the so-called "dimension" is just a superfluous concept whose sole purpose is to help us categorize our senses, due to the fact that a single number can apparently represent multidimensional data. If we suppose that the dimension X only comprises integer values in range [0, 3] and that the dimension Y only comprises integer values in range [0, infinity], for instance, we will simply be able to state that each point in the (X,Y) coordinate system can uniquely be characterized as "X + 4Y", which is just a single scalar quantity.

And the reason why this technical possibility is of importance is that it appears to evince the lack of any necessity to presume the existence of multiple types of qualia which are so fundamentally isolated from one another, that their collective sum can never be expressed as a single numerical value.

Colloquially, I would definitely say that a color and a musical pitch are separate phenomena which belong to separate dimensions. In the strictly metaphysical sense, however, it is not so straightforward to find a decisive proof that they are not just samples occupying different regions of the same exact spectrum of sensory information.

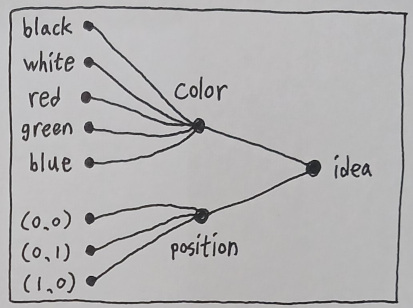

Yet there is a clue which may suggest otherwise. When I think of a multitude of colors, I consider them as specific instances of the same class called "color", which is supposedly distinct from other classes. And a minimal graph-based illustration of this would be a nodal depiction of the idea of "color" which associates itself with the "idea of idea" (because a color is an idea) as well as color variants such as black, white, yellow, cyan, magenta, and so on.

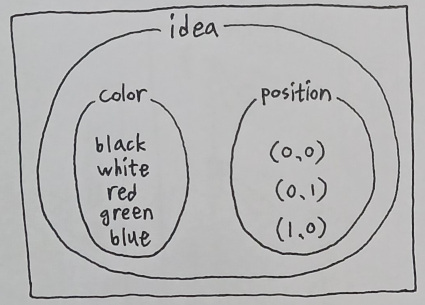

A mathematical interpretation of this is that: (1) The "idea of idea" is the universal set of all ideas, (2) The idea of "color" is a subset of this universal set, and (3) Each specific color, such as "black", is a subset of the "color" set.

The previous multidimensional model fits this set analogy pretty nicely, in the sense that each geometric subvolume of the idea space is a spatial equivalent of a subset. In order to think outside of this tiny box of dimension-oriented reasoning, though, one must break away from the utilization of coordinate axes and begin handling data with a somewhat transcendental disposition of elegance.

(Will be continued in volume 11)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service