Author: Youngjin Kang Date: July 12, 2024

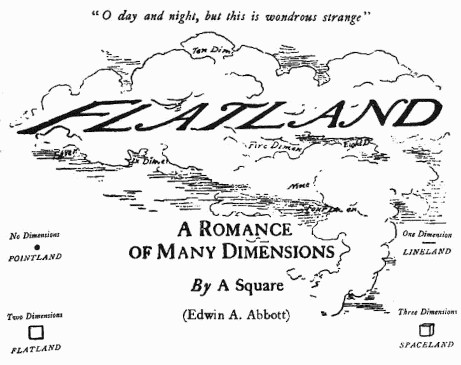

Let me introduce "Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions", a novel written by Edwin Abbott.

There are many novels which can easily be classified as science fiction. On the other hand, it seems to me that there are only a handful of novels which could be classified as "math fiction".

Why is this so? I think one of the most prominent reasons why it is so difficult to find a work of "math fiction" is that math, unlike popular science, is much harder to represent in tangible forms.

While science does possess its own share of profound, esoteric concepts (especially in the field of theoretical physics), we can sort of tell that at least the popular representation of it is full of sparkling rainbow-colored liquid bottles, explosions, spaceships, laser guns, flying robots, and smart-looking British gentlemen in white gowns. Mathematics, on the contrary, offers a lot less to show when it comes to exhibiting its own bread and circuses.

For this reason, it is a genuine surprise to see that the 19th century novel, "Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions", successfully presents us with its own fictional world which is made of purely mathematical ideas yet still manages to entertain us. Starting with the very concept of "dimension" in Euclidean space, the author (Edwin Abbott) invites the reader to his wondrous universe of two-dimensional beings, whose bodies are flat geometric shapes (such as circles, squares, triangles, etc) instead of three-dimensional forms.

The most intricate aspect of this novel is that its fictional universe (aka "Flatland") thrives not only upon the author's imaginative freedom alone, but also upon the way in which the author correlates geometric properties with humanitarian ideas, such as the ones listed below:

(1) The number of sides of a geometric shape represents its rank in the social hierarchy.

(2) Lower-class shapes possess sharp edges, so they can technically kill (i.e. purge) all the round-shaped elites if they want to (This may be an allusion to the French Revolution and downfall of aristocracy in general).

(3) Women are represented by line segments (because they were considered "intellectually narrow" back then).

(4) Nobody in Flatland really understands the existence of higher dimensions because they are inherently narrow-minded (i.e. due to their narrow, "flat" brains), which can be interpreted as religious dogma & persecution.

(5) Visitation of a higher-dimensional entity (before the face of the protagonist called "A Square") signifies a divine revelation, which can never be fully comprehended by lower-dimensional beings.

In a way, therefore, Flatland can be interpreted as a social commentary, a satire, and a metaphor of human nature in general, allegorically conveyed via the language of mathematics. It is truly a multidisciplinary piece of literature, especially if you consider the time period during which it was written.

One piece of criticism against this novel though, which I guess is valid to some extent, is that its narratives tend to be a bit "shallow" compared to those of other famous literary works.

The story of Flatland is primarily centered around the lamentations of the protagonist (i.e. A Square) as a harbinger of truth, who is being persecuted by the mass for revealing provocative ideas. He is the "lone genius" in this fictional universe, who silently rebels against the norm of the mainstream opinion by means of circumventory endeavors (such as writing a treatise which implicitly suggests the existence of the third dimension based upon the hypothetical space called "Thoughtland"), which is kind of reminiscent of how Copernicus dodged the accusations from the religious leaders by claiming that his heliocentric model of the universe is "just a hypothesis which aims to make calculations easier".

Such an "oppressed hero" archetype is indeed a powerful means of reinforcing the reader's ego, since it basically whispers to our ears, "Nobody understands you, but I do! You are the only one who knows the truth, and the rest of the world is to blame!". However, this dichotomous breed of worldview significantly undermines the objectiveness (i.e. value-neutrality) of the overall narrative, thereby giving off cheap impressions which even look a bit embarrassingly juvenile at times.

Nevertheless, Flatland is still an iconic work of classic when it comes to the experimental spirit of the Victorian era. The way in which Edwin Abbott integrated an area of pure academic knowledge into his own narrative world is such a subtle kind of intellectual gem which can hardly be found elsewhere. And I definitely recommend everyone to partake in their journey to Flatland and use it as a fountain of multifaceted inspirations.

(Side Note: The first time I heard about Flatland was when my AP Calculus teacher presented its movie version to his students. He was one of the best teachers I have ever met in high school!)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service