Author: Youngjin Kang Date: 2023.04

(Continued from Volume 10)

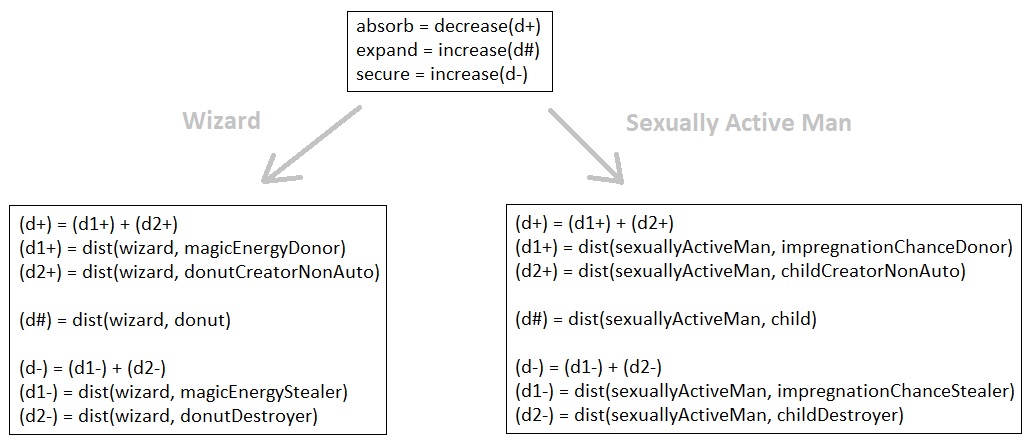

So far, quite a number of concepts have been proposed for the purpose of building an abstract yet universal model of gameplay. Starting from volume 1, I have suggested the possibility of breaking down the goals of any active gameplay agent into 3 major categories - Absorb, Expand, and Secure. And by means of subsequent theoretical development, I have reached the conclusion that these three fundamental goals can be defined in terms of the agent's spatial distances (i.e. costs of traversal) from the 3 distinct classes of atoms that are called "resources", "influences", and "obstacles", respectively.

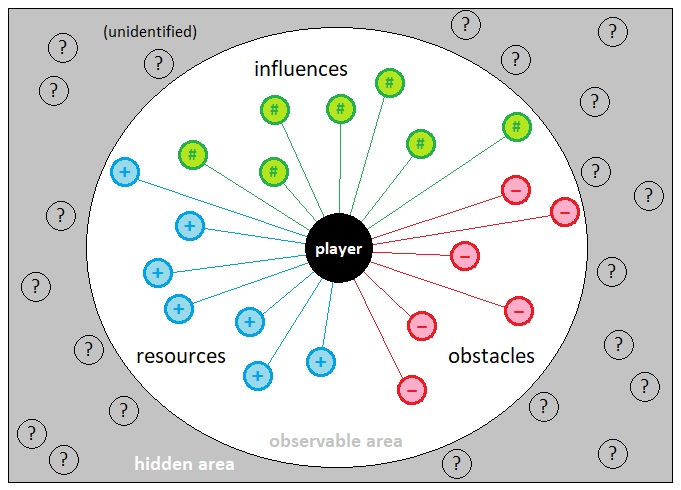

Suppose that the player (aka "myself") is the only active agent of our interest inside the game world (as it is typically the case in most single-player games). In this case, there is only one focal point of observation throughout the whole course of the game's narrative. The entire universe revolves around the player and always puts him/her at the center of the scope of observation, and the narrative space itself can be summarized as the ensemble of the player and his/her relationships with other entities of the universe.

However, the player is not necessarily interested in all types of entities; the kind of entities which are taken into consideration by the player are ones which belong to at least one of the three categories that are commonly referred to as "resources", "influences", and "obstacles", due to the reason that they are directly related to the main character's ultimate purpose in life.

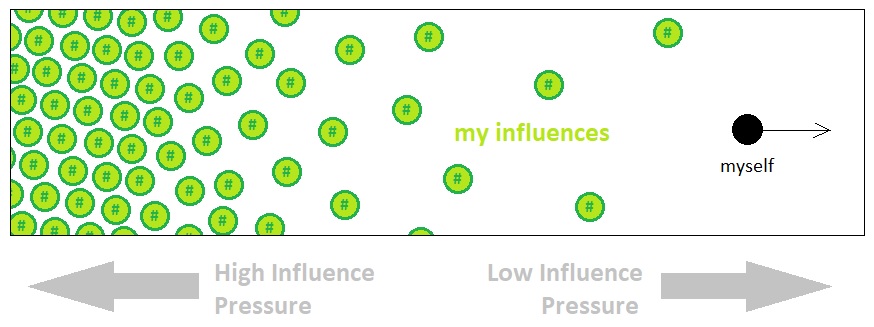

Simply speaking (with a bit of generalization), one may say that the ultimate purpose of any living thing is to increase the size of its "region of influence" as much as possible, which can be done by creating offspring, being present in many places, or by employing any other means of influencing the present set of events whose causal chain reactions may ripple through the tree of future events, in a manner which fits the organism's belief system. And in volume 8, the reinterpretation of the very notion of the concept called "space" allowed us to claim that the desire to maximize the area of one's region of influence can at least be roughly translated into the desire to maximize the total number of one's influence atoms. And we also witnessed the subsequent conclusion that, as long as each position in space has a limited capacity of influence atoms, a creator who constantly strives to generate such influences should endeavor to maximize its average distance from itself and its already made influence atoms (in order to "spread them out" as much as possible).

The problem of increasing or decreasing one's distance from other atoms of a certain class, however, more or less strictly belongs to the mechanical aspects of the game; that is, one's desire to increase or decrease a scalar quantity called "distance" is more of a specific instruction that tells the agent which particular actions ought to be taken in order to achieve a goal, rather than something that is an intrinsic part of the goal itself.

So when trying to design the semantic core of the game's narratives, we need to temporarily forget the distance-based formulation of the agent's three fundamental goals and simply focus on their psychological origins.

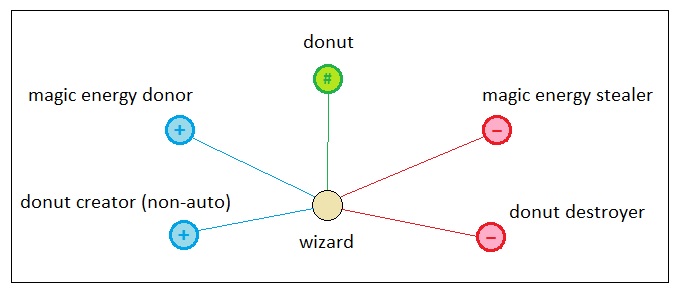

The "Expand" goal, for example, can be described as one's desire to increment the total number of influences. Somebody might ask, "What exactly are influences, anyways?". The answer is, it differs from character to character. If there is a wizard who believes that the only purpose in his life is to turn everything into a donut, we may say that any atom which can be classified as a donut should be considered one of his influences. This makes sense because any abundance of donuts, in this context, would signify the success of the wizard in terms of influencing the world in his own desired way.

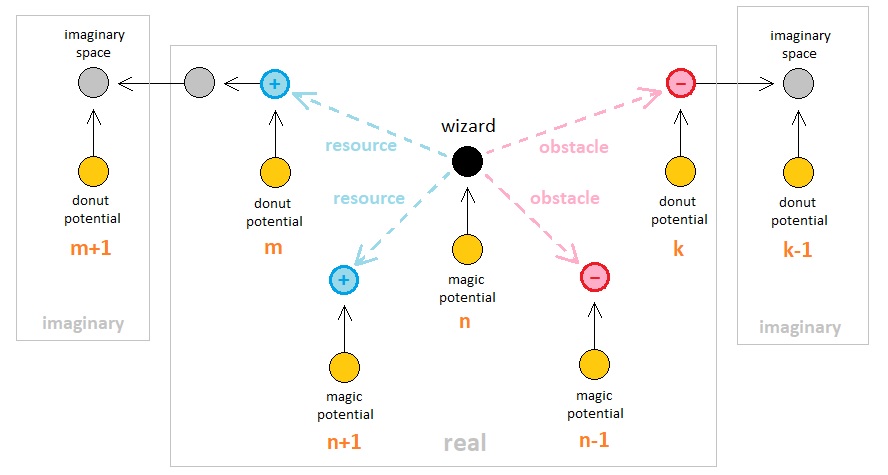

The "Absorb" goal can be described as one's desire to be in touch with as many resources as possible, where each resource is basically an atom that is capable of donating certain types of energy particles which induce the agent to increase its total number of influences. For instance, any atom which is able to grant magic energy to the wizard (such as a mana battery) must be identified as a resource, since more availability of magic energy particles means more chances for the wizard to convert a non-donut into a donut. Any atom which creates brand new donuts whenever it is in contact with the wizard, too, must be considered a resource because it donates "donut energy particles" (aka "donuts") into the wizard's domain of existence, and because the presence of each donut energy particle helps the wizard maintain his total number of influences to be 1 higher than it would have been otherwise). An atom which automatically generates donuts without requiring the wizard's involvement does not count as a resource because such a behavior matches the expected behavior of the wizard and therefore qualifies the atom as an extension of the wizard himself.

The "Secure" goal, on the other hand, can be described as one's desire to avoid being in contact with obstacles, where each obstacle is basically an atom that is capable of stealing energy in a way in which it interferes with the process of maximizing the agent's number of influences. For instance, any atom which is able to take magic energy away from the wizard (such as an instance of the "expelliarmus" spell in Harry Potter) must be identified as an obstacle, since less availability of magic energy particles means fewer chances for the wizard to convert a non-donut into a donut. Any atom which destroys donuts, too, must be considered an obstacle because it steals "donut energy particles" (aka "donuts") from the wizard's domain of existence and sends them to imaginary space, therby reducing the wizard's total number of influences.

To summarize, I would say that the narrative characteristic of each active gameplay agent can be specified in terms of:

(1) The types of the agent's influences,

(2) The types of atoms which donate energy in ways in which they help preserve/increase the number of influences (aka "resources"), and

(3) The types of atoms which steal energy in ways in which they hinder the process of preserving/increasing the number of influences (aka "obstacles").

In the case of the wizard who is weirdly obsessed with donuts, we can say that:

(1) Any donut counts as one of the wizard's influences because his ultimate purpose is to increment the number of donuts as much as possible,

(2) Any atom which is capable of donating magic energy to the wizard, or is capable of creating a donut when in contact with the wizard, counts as one of the wizard's resources, and

(3) Any atom which is capable of stealing magic energy from the wizard, or is capable of destroying a donut, counts as one of the wizard's obstacles, and

(4) Any atom which has a tendency of creating donuts on its own is part of the wizard himself (That is, either his own body or his offspring).

The next question is, what would be the underlying mathematical pattern on top of which we are bound to decide exactly what types of atoms qualify as influences, benefactors of influences, and malefactors of influences?

In my view, the key to answering this question solely depends on the problem of figuring out which types of atoms qualify as one's influences. The reason behind this is that, once we know which atoms are supposed to be the observer's influences, we can easily derive the identities of atoms which pertain to the definition of resources and obstacles (i.e. those that either enhance or attenuate the process of keeping/incrementing the total number of influences) based upon the game's mechanical structure. The act of summoning a donut comes with the expenditure of one magic energy particle not because the wizard's profound belief system enforces them to be related in such a way, but because such a relationship is just an inherent law of causality embedded in the physical reality of the gameplay universe. It is the same idea as that a steam engine converts thermal energy to kinetic energy simply due to the fact that these two types of energy are mechanically related in such a way under specific circumstances, not necessarily because there are angels and spirits who believe that their purpose of existence is to turn heat into motion wherever there is a steam engine.

And from our daily observations, we can easily infer that every living thing possesses its own definition of which atoms are its influences and which atoms are not. Such a definition is the heart of one's belief system - a fountain of narratives from which all sorts of motivations sprout and flourish.

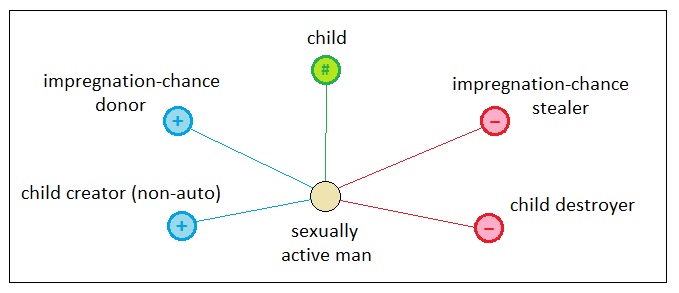

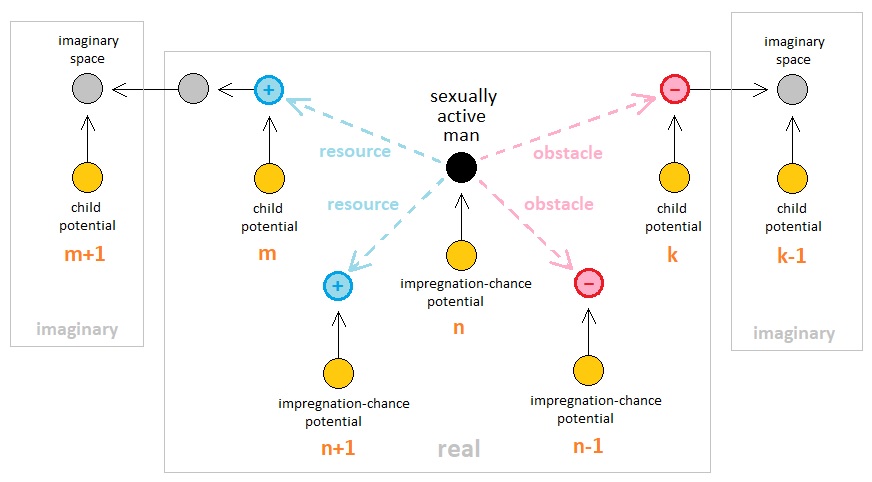

Let us imagine that there is a sexually active man who believes that the purpose of his life is to have as many children as possible. Inside his worldview, his own children are his influence atoms and anything which contributes to the creation of his children is a resource (And of course, anything which has the opposite effect is an obstacle). This means that his current wife, potential future wives, prospective recipients of his sperm donation, and Viagra pills are all his resources because all of them provide him with "impregnation-chance energy particles" which, when consumed via exchanges, transfer his children (i.e. influences) from imaginary space to real space, thereby incrementing the total number of his influences.

The exact set of atomic interactions involved during the full process of attraction, intercourse, impregnation, and birth, are not so simple to design as to be demonstrable right away, yet one can easily guess that they can be built out of analogous representations of our physical reality, parts of which have the freedom to be more or less fictional to a fair extent. One may say that representing abstract concepts (e.g. chance of reproduction, fertility, sexual selection, etc) as atoms and their pseudo-chemical interactions over-simplifies things a bit too much, yet we know that this is a kind of generalization we ought to pursue in order to reason with abstract concepts in an efficient manner.

Here is a quick example to back up the statement above. A game character's overall physiological fitness is often being represented as a single health bar, since a game is a work of fiction which has the right to employ any means of unrealistic simplification for the sake of convenience. Likewise, various motivational factors and their ensuing patterns should have everyone's permission to be modeled in a manner which fits our design intentions rather than the so-called "objective reality". We may say that an intercourse is an exchange between one impregnation-chance energy particle and one birth-chance energy particle (Or, in the context of accounting and finance, a transaction which involves a unit loss of impregnation-debt and a unit gain of birth-credit), which is more or less just a fictional model of the full process of procreation but still successfully renders the end result in a satisfying manner. The intermediary processes can be ignored during the game's early prototyping stage, since such details can be filled out later on in a fairly modular fashion.

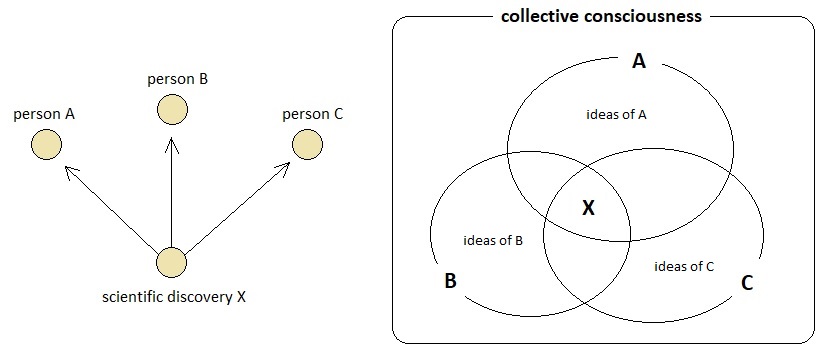

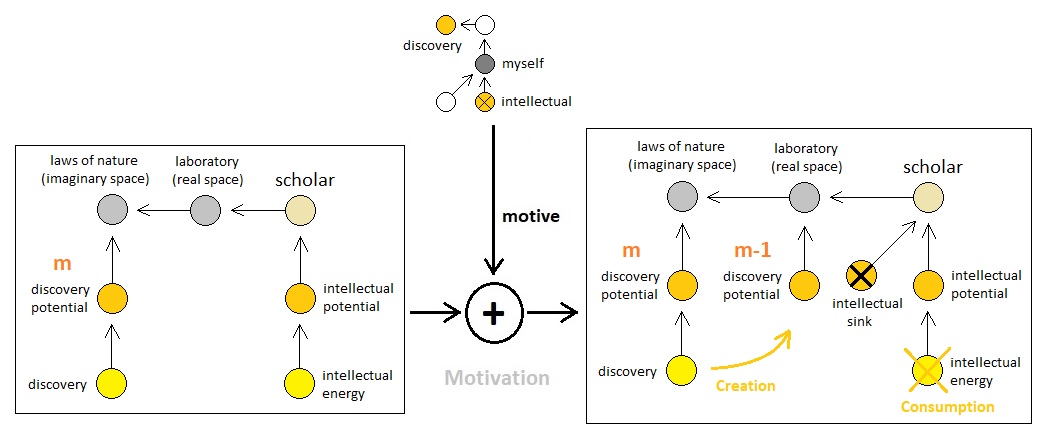

Here is another example of what determines the identity of one's influence. Let us imagine that there is a highly scholastic man who believes that the only purpose of his life is to make as many scientific discoveries as possible (which qualifies them as his influences). And due to this strong belief which prioritizes his academic career over any other activities, this man is never willing to start a family and have kids.

This is a somewhat trickier scenario because a "scientific discovery" is not nearly as straightforward to define as one's descendant. A child is a biological organism (i.e. an object) which has its own mass and other tangible features, and therefore it makes sense to be represented as an atom (just like a rigid body can be represented as a point mass in physics). A discovery, on the other hand, may refer to either a piece of information or a methodology for accessing a piece of information, which is not really a physically locatable unit of existence and is therefore more or less "distributed" throughout the causal web of space and time.

Again, however, we should remind ourselves that the thing we are trying to design is a game which does not need to portray our physical reality with pinpoint accuracy; it is a fictional universe in which it is okay to represent non-spatial entities as spatial entities and vice versa.

Let us put all sorts of epistemological complexities aside as though they do not exist, and simply assume that any scientific discovery is just a single atom which simultaneously belongs to every place in which it is being conceived. If three people who are respectively named A, B, and C, are the only ones who are aware of a scientific discovery called X, for instance, one could illustrate X as an atom that is bound to A, B, and C. Such a mode of simultaneous bindings indicates a spatial intersection that is being shared by 3 different regions within the space of collective consciousness.

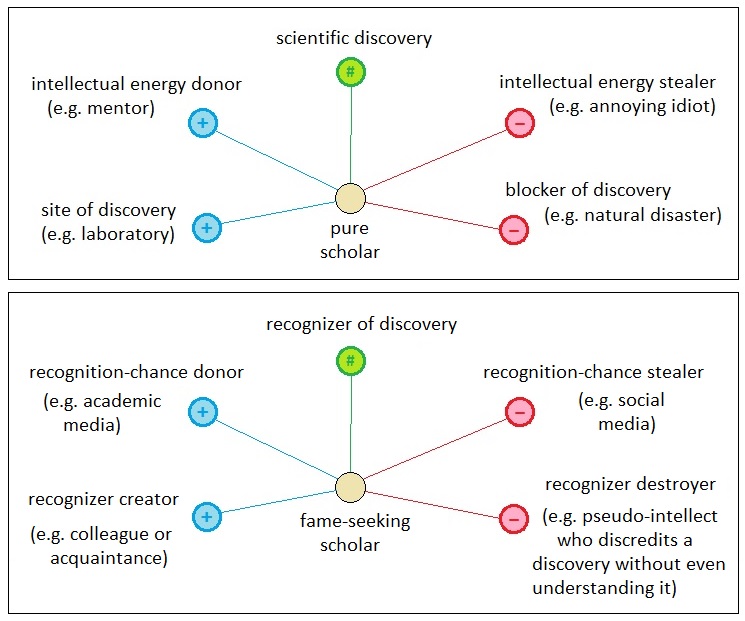

If this scholastic man does not seek fame (public recognition) at all, the number of such bindings which are associated with each scientific discovery won't matter that much to him. The only metric of personal success within the worldview of this dedicated scholar will be the total number of scientific discoveries which were created by himself. This means that, as long as the aforementioned condition holds, any atom which can be identified as a "scientific discovery" automatically qualifies as an influence of this man.

And since a variety of different scientific discoveries can be made only in distinct circumstances which are spatially separate from one another (e.g. a laboratory, a volcanic site, a top of a mountain, a space probe, a telescope, a microscope, an archaeological site, and so on), one could fancy that there are a multitude of imaginary-to-real energy transfer pathways existing within physical sources of scientific discovery. In each one of them, the scholar should be able to conjure a new scientific discovery (i.e. his influence) by means of intellectual motivation, thereby increasing the total number of his influences.

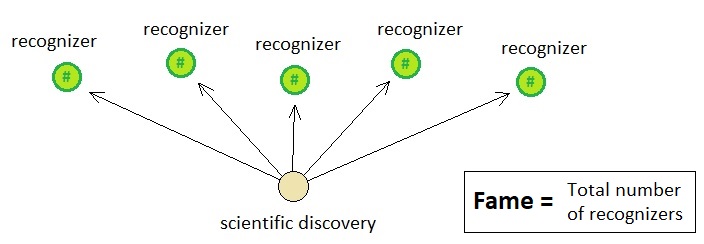

If this man were more of a fame-seeking person than a pure explorer of truth, on the other hand, we would need to interpret things a bit differently. Unlike in the previous case in which the man measured his degree of success in terms of the total number of scientific discoveries that were made by himself, this fame-seeking scholar must be measuring his degree of success in terms of the total number of recognizers whose origins of recognition can be attributed to his own scientific discoveries.

The problem of identifying resources and obstacles depends on what is the primary goal of the scholar. If his focus is to make as many discoveries as possible, one must say that any atom which directly boosts this man's ability to create a new discovery (e.g. a source of intellectual energy, a site of scientific observation, etc) can be defined as a resource and any atom which has the opposite effect can be defined as an obstacle. If the man's focus is to become a famous figure in the field of science, on the other hand, one must say that any atom which directly boosts this man's ability to make people remember his own discoveries (e.g. a person who is willing to learn about his discoveries, a book publisher that is willing to publish a paper on his discoveries, etc) can be defined as a resource and any atom which has the opposite effect can be defined as an obstacle.

This kind of abstract reasoning can go on and on forever, expressing abstract entities in the form of atoms and their transactional relations. Happiness, sadness, anger, fear, jealousy, fondness, empathy, and myriads of other types of emotions, too, can be used to represent somebody's influence atoms which may come into existence under the execution of emotional energy exchanges (aka "emotional transactions").

Since our imaginative freedom does not prevent ourselves from making up abstract playgrounds of meaning upon which every gameplay agent possesses its own definition of resources, influences, and obstacles (as was demonstrated so far by means of multiple examples), and since these 3 classes of atoms directly correspond to the 3 most fundamental goals of every animate object (i.e. Absorb, Expand, and Secure) each of which has its own precise list of mechanical instructions that can easily be translated into computational procedures (See volume 2), it is reasonable for us to conclude that the whole behavioral spectrum of any agent within the game is reducible to a set of mathematical formulas as long as we manage to specify the means of identifying resources, influences, and obstacles of every agent. And we know that, if a conceptual model can be represented mathematically, it will be not so difficult for us to reduce its nature down to the most minimal set of metrics (e.g. distances and energy levels) while also being able to quantitatively expand its scope in an unbounded manner.

Let's go back to the example of the sexually over-active man. A man whose purpose in life is to make as many children as possible will identify his children as his influences, fertilizable women as his resources, and rivals who interfere with his child-making process (such as other men of his age) as his obstacles. The implication of this is that such a man is expected to:

(1) Decrease the average distance of his own body from fertilizable women by approaching them and laying down intermediary energy-transfer bridges between himself and those women as much as possible (This corresponds to the execution of the "Absorb" goal),

(2) Increase the average distance of his own body from his own children by avoiding them as much as possible, since their moms will take care of them anyways and his foremost goal is to increment the total number of children instead of ensuring their overall well-being (This corresponds to the execution of the "Expand" goal), and

(3) Increase the average distance of his own body from other men (sexual competitors) by either avoiding them or kicking them out to other places that are as far away as possible, among which the heaven could have been a strong candidate if the law did not prohibit it (This corresponds to the execution of the "Secure" goal).

In real life, of course, a man is not that extreme in his behaviors. A man, while he may subconsciously possess a strong tendency to seek every chance of reproduction, usually spends some time taking care of his wife (wives) and kids, doing some laundry, washing dishes, working for a job, and so on, unless he is a primeval super-alpha male with a somehow short-circuited brain.

So for a more realistic model of a gameplay agent, we will need to come up with multiple definitions of influences, multiple definitions of resources, and multiple definitions of obstacles depending on a set of values that are originated from not only sexual instincts, but also other volitional factors which are moral, aesthetic, sympathetic, and philanthropic in nature. Such a multitude of beliefs can be translated into a multitude of parallel goals which compete with each other in real time, and the problem of sorting out their relative degrees of prioritization is a separate issue that is yet to be settled down.

However, in the context of game development we do not necessarily have to aim for realism, and therefore are not required to keep multiplying the complexity of one's goal structure beyond our control. After all, an enemy character usually only cares about attacking the player and hardly anything else. In more volitionally complex games (such as The Sims) we can clearly perceive agents with multiple sources of motivation that are in competition with one another (such as Hunger, Bladder, Energy, Hygiene, etc), yet their number is fairly limited and all of them are handled by a set of strictly quantitative laws, which keep them pretty manageable in terms of design and implementation.

(Will be continued in Volume 12)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service