Author: Youngjin Kang Date: January 21, 2025 - February 28, 2025

This is a collection of my personal thoughts on the design of a software product.

Imagine that you are trying to design a software product. Depending on your field of interest, it could be a game, a social networking service, a chatbot, an educational platform, or something else.

No matter what type of product you have in mind, however, we can all agree that it ought to be something meaningful. And by "meaningful", I mean a set of qualitative measures which transcend a mere assortment of dry, mechanistic details.

When designing a software, it is necessary to resolve a gap between the product's end goal and its implementation details. We can surmount this difficulty via quantitative reasoning.

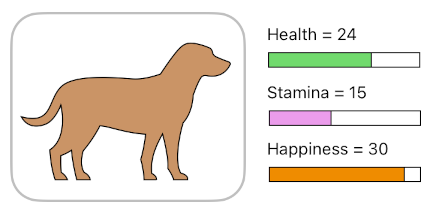

For example, suppose that we are trying to create a pet simulator (similar to Tamagotchi). What shall we do to fulfill such an objective?

First, we need to devise a list of meaningful pet-related experiences. In addition, we need to figure out how to translate them into computational procedures (because they must be part of a computer program).

We can achieve this by defining our pet simulator not in terms of vague emotional descriptions, but in terms of numerical quantities.

The question is, what kinds of numerical quantities do we want in our pet simulator?

This is where the problem of ambiguity arises. Overcoming this initial barrier is crucial for the sake of designing something meaningful.

To kick-start the design process, let me come up with a couple of ideas. The very first thing which crosses my mind is that the pet needs food to survive.

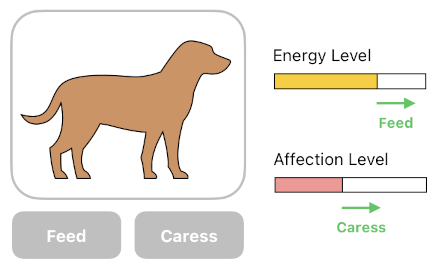

Whenever the pet eats something, its energy level increases. If it doesn't eat anything, its energy level will gradually drop.

What comes next? Let me guess. Note that food is not the only biological need. For example, the pet also needs to be caressed to feel that it is being loved.

For prototyping purposes, then, it will be sensible to add a pair of buttons to let us interact with the pet - one for feeding, and the other one for caressing. Clicking the former will increase the energy level, while clicking the latter will increase the affection level.

Here, we can see an example of a dilemma between two choices. While we are feeding the pet, it cannot be caressed. And while we are caressing the pet, it cannot be fed.

The design of a virtual pet, then, can be summarized as the following two steps:

(1) Create a set of variables, each of which represents a unique aspect of the pet's state.

(2) Create a set of actions, which either increment or decrement these variables when invoked.

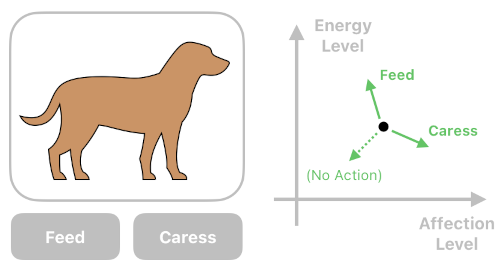

The act of feeding, for instance, may greatly amplify the pet's energy level but slightly reduce its affection level. The act of caressing, on the other hand, may greatly amplify the pet's affection level but slightly reduce its energy level.

And if we spend time without doing anything, both the pet's energy and affection levels can be expected to decay as time passes by.

The dynamics of pet simulation can be easily visualized. For example, we can treat the pet's current state as a particle on a 2D plane, whose axes denote the pet's energy and affection levels, respectively.

Each action, then, will be interpreted as a force which pushes the particle in a specific direction.

So, it looks like introducing a few variables and means of manipulating them will let us create a simple pet simulator.

This solution, however, is restrictive in the sense that it does not scale. If we are to stick solely to the idea of raising a single pet, the horizon of our experience will forever be constrained to that of a cheap electronic toy, such as Tamagotchi.

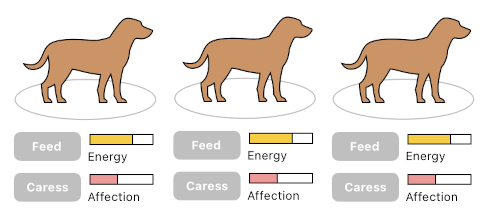

There is a way to overcome such a barrier, though. All we have to do is provide the user with multiple pets instead of just one. This will open up a door to a richer spectrum of choices, without necessitating us to invent anything new.

From a game design point of view, such a means of scaling introduces the notion of progression. By adding more and more pets to the inventory, the user is now able to participate in a mission towards continual improvement.

This is an indispensable feature to have, as it is necessary to ensure that the user won't run out of goals to pursue.

Previously, we saw that letting the user own multiple pets (instead of just one) neatly solves the scaling issue.

If pets are unable to interact with each other, however, the overall experience will be too flat and boring.

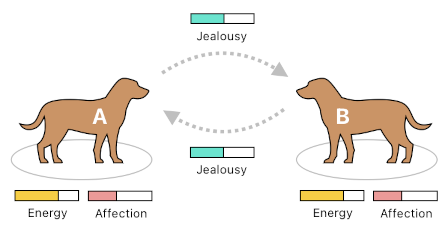

One way to solve this is to invent a variable which describes not just a single pet, but a relationship between two pets.

For example, we may come up with a new variable which represents the degree of jealousy that a pet feels towards another pet. We will then be able to declare a rule such as: "Pet A becomes more jealous towards pet B whenever the user caresses B in front of A".

The main benefit of this is that it introduces a wide variety of dynamic behaviors to the system. Too much jealousy, for instance, may trigger a pet to start a fight with another pet, resulting in mutual damage.

Such a conflict of interests serves as an important factor in the design of subtle narratives. It urges the user to make choices carefully, since each choice may incur a catastrophic side effect.

We may imagine a pet simulator as a network of pets and their relationships.

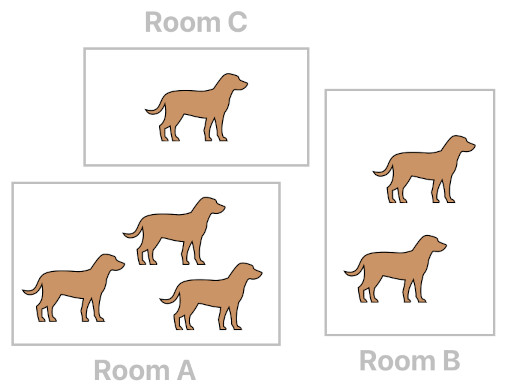

If every pet is capable of interacting with every other pet at any given moment, however, the whole system will plunge into chaos.

The most effective solution to this is to partition our simulation space into rooms that are separate from each other, meaning that pets in one room won't be able to interact with those in another room.

Such a mechanic allows us to create local environments, each of which is imbued with its own personality. It also provides the user with an extra dimension of self inquiry, such as: "Should I put these two pets in the same room? They might fight with each other."

Another advantage is that it makes things more digestible. By splitting a large herd of pets into isolated groups, the user is now only required to pay attention to a handful of them at a time, rather than having to monitor the entire community of pets like an omniscient deity.

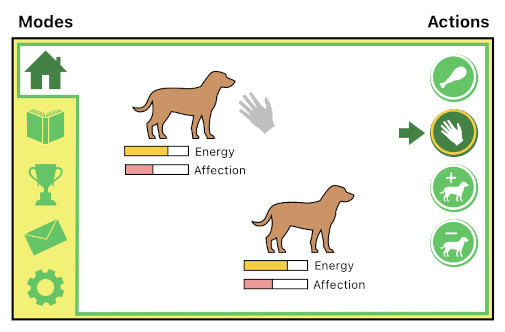

The richness of user experience can be further amplified by splitting it into multiple channels.

In our pet simulator, for example, the user might be allowed to not only take care of one's pets, but also send them to schools, consult a vet, visit a local pet shop, and so on. Since these activities differ from each other significantly, we may assume that they belong to separate classes.

The overall structure of the UI, then, could be depicted as a list of global menu options. Each of them, when clicked, will bring the user to a distinct local space, equipped with its own category of user interactions.

The exact layout of this sort of UI may vary, of course, depending on what kind of product it is intending to convey.

What is noteworthy, though, is the fact that it prevents confusion by neatly segmenting the system into specialized modules, each of which focuses on its own topic and nothing else.

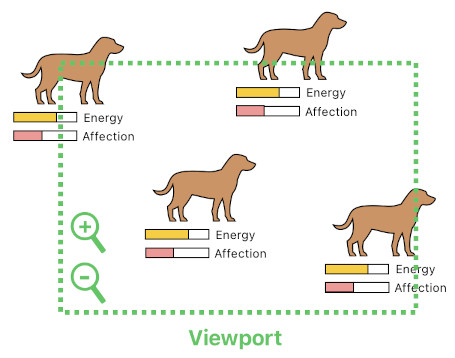

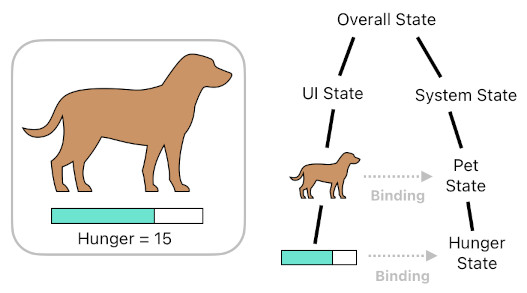

When we think about a software product as a state machine (as in automata theory), we quickly come to the conclusion that it consists of two distinct types of state - one which is bound to user interaction (aka "UI State"), and the other one which is bound to the system's internal dynamics (aka "System State").

The UI state mirrors the way in which the user is currently interacting with the app's virtual world. The dimensions of the viewport (i.e. camera), the position of the page's scollbar, the current menu selection, and the like, are all parts of the application's UI state. They do not directly influence things that are happening in the world.

The System state, on the other hand, refers to the current state of the world itself. In our pet simulator, for example, the individual pets' positions and energy/affection levels should all be taken as parts of the application's System state because they all contribute to what is happening inside the world.

A software product, regardless of its kind, possesses its own state. An important concept to keep in mind is that the state itself may be broken down to smaller states, each of which can then be broken down to even smaller states, and so on.

Eventually, this sort of breakdown reveals its own hierarchical structure.

Based on this kind of reasoning, we can easily design the entire tree of states from a top-down perspective. All we need to do is first define a few general state objects, and then describe each of them as a collection of more specific state objects, and so forth.

What is interesting is that there are direct one-to-one mappings between states which are equivalent but designed to serve different purposes.

The state of the UI which displays the current hunger level of a virtual pet, for instance, could be bound to reflect the actual hunger level of the pet to which it corresponds. This is an example of "UI binding" - a recurring concept in the domain of reactive programming.

Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service