Author: Youngjin Kang Date: June 3, 2024

(Continued from Part 5)

Therefore, the more I look inside the hidden intricacies of ideas and their associations, as well as the sheer impossibility of discovering the ultimate root of their definitions, the more I cannot help myself concluding that the world of ideas is one vastly intertwined fabric of mutual dependencies which must be regarded as it is, never meant to be decomposed into clean pieces.

And it is a true disappointment to be witnessing such a rigid intellectual bedrock, for it means that one's last remaining path of investigative freedom is faith alone, and that none of the cunning bits of sophistry will replace it except in the ivory tower of academic word play and metaphysical masturbation.

So, how to overcome this major obstacle? I would say that there are two major solutions.

One is to keep identifying all sorts of ideas and associations in the most strictly logical manner as possible, by using fancy math equations and stuff. Once we choose this hardcore route, we will have to carefully dig through the labyrinth of details and always take caution not to let them contradict one another.

Building rules upon rules and theorems upon theorems, we may eventually acquire a faint glimpse to the overall landscape of our universe. We may even manage to thoroughly dissect a small region of ideas in the midst of the sea of chaos, render the full anatomy of it, and use it as a stepping stone towards a better understanding of the subject. This, however, is a wishful daydream. The exploration might as well lose its momentum at some point, leaving us confounded by the snowballing body of complexity.

The other solution is to simply give up the notion that we are ever going to figure out the "absolute truth" of the subject, and simply resort back to the primordial mindset of picking and choosing what works for us from a practical standpoint.

The reason why I started mentioning ideas, associations, and their vast relational assembly in the first place, was to come up with an easier way of depicting various events in life.

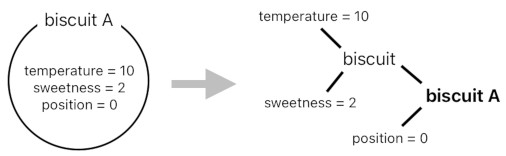

For example, the "bake" function was originally defined as a process of receiving a collection of numbers (i.e. a piece of dough) and turning it into another collection of numbers (i.e. a biscuit). This sort of approach was deemed too notationally verbose, so I came up with a new conceptual model which characterized such parameters in terms of ideas and their associations.

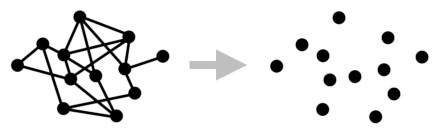

The thing is, if this graph-based worldview introduces more bits of complexity to our faculty of reasoning than the ones it promises to get rid of, there is no reason for us to keep using it. The whole purpose of devising such a theoretical construct was to help us develop a better understanding of what really happens when we bake something. Why should we preserve such a construct as it is, then, if it fails to serve its designated role?

If one model does not work, the most sensible alternative is to replace it with another one which solves the problem more effectively.

The goal is quite obvious here. We want to build a new model which lightens the weight of our mental labor. Such a model does not need to be completely different from the original, though; we only need to "tune" the existing thing in an intuitively satisfying way by replacing some of its convoluted parts with simpler analogues.

A gigantic web of associations among ideas, for instance, is too confusing. So let us just entirely exclude the concept of association from our system.

Also, there is no compelling reason for considering some of the ideas as "abstract". As I have demonstrated before, the very notion of abstraction itself is pretty darn subjective anyways, as it largely depends on our cognitive preference.

So, why not just depict every single idea as a tangible object - that is, a solid particle with its own mass, volume, and a location in physical space? It doesn't matter whether an idea is supposedly abstract, vague, or invisible. All ideas, both universal and particular, concrete and abstract, dim and vivid, can neatly be depicted as rigid bodies following Newton's laws of motion.

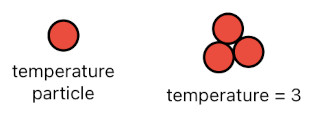

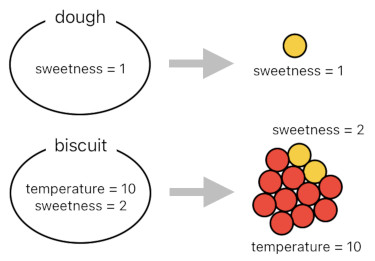

In this brand new model of the universe, everything appeals to our senses in the most blatantly direct manner as possible. Numbers are for counting things, and a quantitative measure (e.g. "temperature", "sweetness", "position", etc) is simply the number of copies of its corresponding particle. The idea of "temperature = 3", for example, can be characterized by the bondage of 3 temperature particles.

A piece of dough, then, is nothing more than a single sweetness particle, and a biscuit is the composition between 10 temperature particles and 2 sweetness particles.

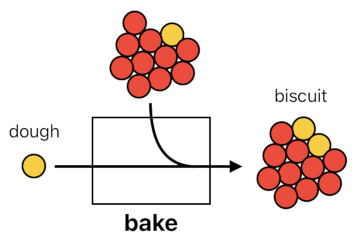

The "bake" function is a particle-processing machine. Whenever it takes 1 sweetness particle (aka "dough") as the input, it returns a molecule of 10 temperature particles and 2 sweetness particles (aka "biscuit") as the output. All it does is to add 10 temperature particles and 1 sweetness particle to whichever raw material it happens to bake.

Algebraically, such a process is simply described as:

bake(input) = input + 10 temperature + 1 sweetness

The "temperature" variable represents a temperature particle, and its multiplier (10) indicates how many of its copies are being added to the input. Likewise, the "sweetness" variable represents a sweetness particle, and its multiplier (1) indicates how many of its copies are being added to the input.

We know that, when we bake a piece of dough, we obtain a biscuit.

biscuit = bake(dough)

A piece of dough is the same thing as a single sweetness particle. That is,

dough = 1 sweetness

Therefore, baking a piece of dough can be characterized as:

bake(dough) = bake(1 sweetness) = 1 sweetness + 10 temperature + 1 sweetness = 10 temperature + 2 sweetness

Since a biscuit is just a combination between 10 temperature particles and 2 sweetness particles,

biscuit = 10 temperature + 2 sweetness

We are able to conclude that the "bake" function's formula perfectly matches our expectation.

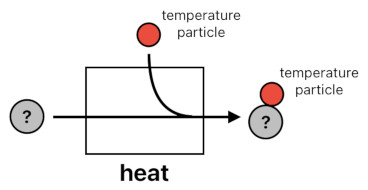

This sort of logic, with the aid of intuition, easily expands itself beyond the case of dough and biscuit. Our common sense tells us that the process of heating an object is the same thing as adding an extra temperature particle to it, for instance.

heat(input) = input + 1 temperature

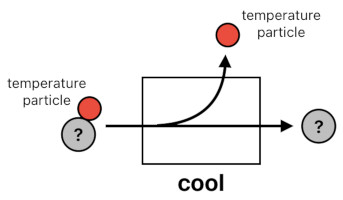

We also know by intuition that the process of cooling is basically the opposite of heating - that is, subtracting a temperature particle from the given object.

cool(input) = input - 1 temperature

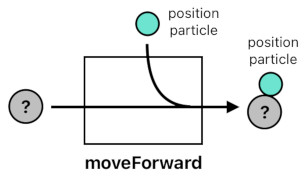

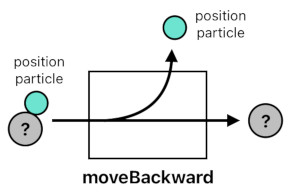

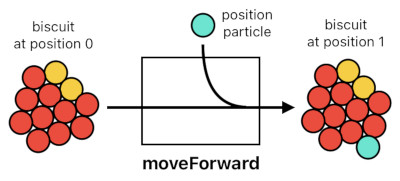

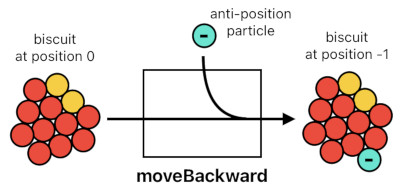

What about moving an object? Just like the object's current degree of temperature can be represented by its number of temperature particles, its current position can be represented by its number of position particles. For example, if the position is 1, there will be 1 position particle, and if the position is 2, there will be 2 position particles, and so on. Thus, the process of "moving forward" is the same thing as adding a position particle, and the process of "moving backward" is the same thing as subtracting a position particle.

moveForward(input) = input + 1 position

moveBackward(input) = input - 1 position

For example, you can move your biscuit forward in space by giving it a position particle.

moveForward(biscuit) = biscuit + 1 position

Does your biscuit have no position particle at all, but you still want to move it backward anyways? Add an anti-position particle, then (denoted by "-position" instead of "+position").

moveBackward(biscuit) = biscuit + 1 (-position) = biscuit - 1 position

A biscuit with 0 position particle is a biscuit located at position 0, and a biscuit which has 1 position particle is a biscuit located at position 1. Likewise, a biscuit which has -1 position particle (i.e. "1 anti-position particle") is a biscuit located at position -1.

The concept is pretty simple. Every attribute of an object (e.g. "temperature", "sweetness", or "position") is a distinct particle type, and the attribute's quantity is determined by the number of particles which belong to that specific type.

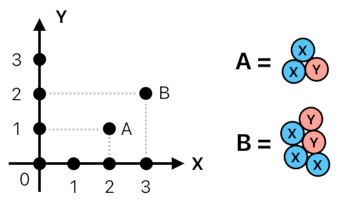

In this new worldview, a two-dimensional point in space can be expressed as a composition of X particles and Y particles. The number of X particles indicates the x-coordinate of the point, and the number of Y particles indicates the y-coordinate of the point. You can change the location of this point by changing the number of its X and Y particles (X for horizontal movement, Y for vertical movement).

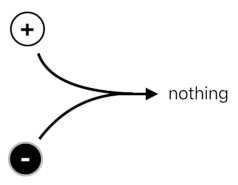

When a particle meets an anti-particle of the same type, they both disappear. This is because two opposing forces cancel each other out.

The benefit of imagining things based upon a mechanical analogy like this, is that most of the details (e.g. ideas and their associations) are implicitly being handled by its underlying physics.

(Will be continued in Part 7)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service