Author: Youngjin Kang Date: May 31, 2024

(Continued from Part 4)

Let us reiterate a bit.

Our world is filled with ideas, which are as numerous as stars in the night sky. Ideas are associated with one another, and associations are what gives meaning to the ideas.

Ideas and associations make up constellations in the heaven, which shine for eternity because they exist outside of space and time.

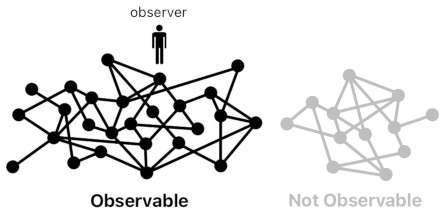

Each separate constellation is its own isolated chamber of vision. A spirit whose vision is stuck in one chamber is never able to see another, since there is no bridge to transfer the spirit's point of view from the one to the other. Our material universe, which we all share in common, is one big constellation in which everything we know happens. Ideas residing in other (disjoint) constellations can never be reached by our eyes, and thus lie beyond the boundary of human comprehension.

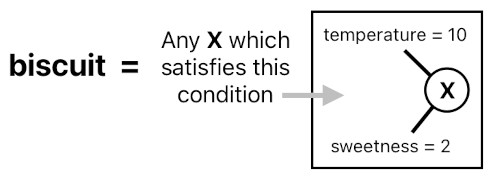

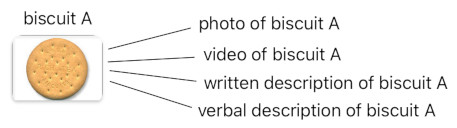

What grants identity to an idea is not its name, but the way in which it is being associated with other ideas; a name is just an artifact invented by humans for the purpose of communication. This brings us back to the prior illustration of the idea called "biscuit" and its characteristics.

How do we know that a biscuit is a biscuit? In real life, it will be quite tricky to provide an accurate answer because there are countless types of biscuits, many of which may exhibit a wide range of small differences. Inside the hypothetical universe I have previously shown, however, a biscuit is any object which has the temperature of 10 and sweetness of 2.

The key point of such a definition is that we identify the idea of biscuit with the word "biscuit" not because we have a special reason for choosing this specific word, but because this idea is associated with two other ideas which can be described as "temperature = 10" and "sweetness = 2".

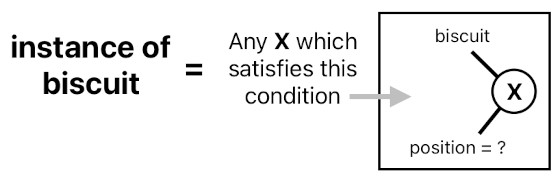

Similarly, we know that an idea is an instance of biscuit (rather than the very idea of "biscuit" itself) not when its name suggests so, but when it is associated with two other ideas - one which could be identified as "biscuit", and the other one which could be identified as a particular position in space (e.g. "position = 0").

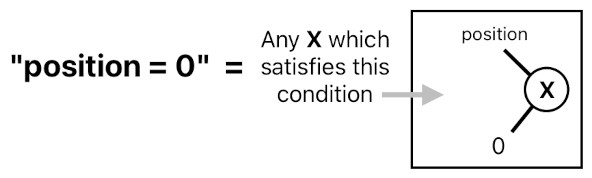

How do we know that the idea of "position = 0" denotes the idea of a spatial point located at 0, then? This one is fairly straightforward, too, since we know that any idea which is simultaneously associated with "position" and "0" is essentially what the idea of "position = 0" claims to be. No confusion here so far.

But hold on! Here is where things get really tricky.

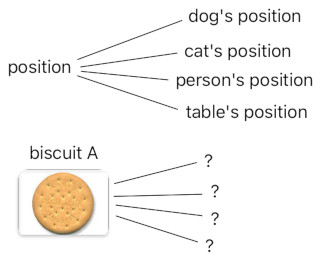

How do we know that the idea of "position" itself refers to what we mean by "position"? The fact that it is associated with numerical values (e.g. 0, 1, 2, 3) is of no help here because there are tons of other ideas with the same exact kind of quantitative relations, such as "temperature", "sweetness" etc.

The thing is, we somehow know by heart that "position" is something which qualitatively differs from other equally sublime attributes such as "temperature" and "sweetness". Our faculty of sensation tells us that a biscuit's position is of a fundamentally separate nature from its temperature or sweetness.

Yet, as we ponder upon the ways in which some of the other ideas are being defined, we begin to notice a morsel of clue lurking in the back of our minds.

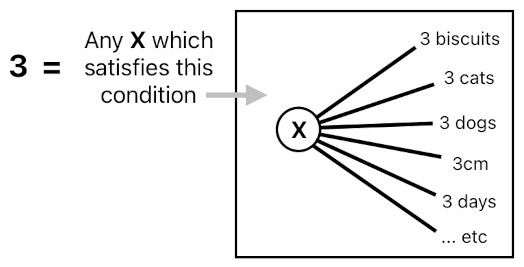

For example, how does the idea of "3" justify its own presence as number 3, and not 1, 2, or some other number? There could be a multitude of alternative definitions, but the most reasonable one is to define the idea of "3" as one which happens to associate itself with every instance of number 3.

There is the idea of "3 biscuits", as well as the idea of "3 pieces of dough". There is also the idea of "3 cookies", "3 houses", "3 people", "length of 3 meters", "duration of 3 seconds", and so on. All these ideas bear the sense of 3-ness in them, and if there is one idea with which all of them are associated, we can conclude that it must be the idea of "3".

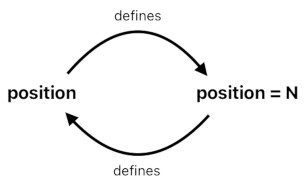

Similarly, we may define the idea of "position" as the one with which all position-bearing ideas are associated - that is, ones that are being worded as "position = 0", "position = 1", "position = 2", etc.

Such a line of argument appears to be circular, though. If "position" is defined in terms of its relations to "position = N" (for any arbitrary number N) and "position = N" is defined in terms of its relations to "position", all we are left with is a mere conceptual short circuit, contrived to bypass the logical dead end.

Therefore, we need an external piece of puzzle to grasp the essence of these seemingly inexplicable ideas (e.g. "position", "temperature", "sweetness").

The first barrier we ought to dismantle is the underlying assumption that ideas which pertain to tangible objects are any more self-explanatory than those which are deemed abstract.

For instance, we all know that "position" is a highly generic concept, and thus cannot quite explain its own nature except by means of real-life examples, right? We need at least some diagrams, written symbols, or anything which can directly appeal to our senses, in order to feel the existence of such an abstract entity.

In contrast, let us imagine that there is a biscuit sitting on top of a table. You and I can clearly see it, touch it, smell it, and eat it. We decided to call this particular object "biscuit A".

Since we can directly perceive this object, it feels like we do not need any more insight to understand it further. This particular biscuit is simply what our senses tell it is, isn't it? What else do we even need to know more about it?

The problem is that such an implicit delegation of reason is just as insincere as the claim that the idea of "position" is simply what its real-life examples show it is. If we define "biscuit A" based on the way it speaks to our senses, and if we also define "position" based on the way it speaks to our senses (by means of examples), can we really assure that there is a fundamental difference between "biscuit A" and "position", in regard to the certainty of their existence?

One might insist that the object called "biscuit A" must obviously be way more self-explanatory than, say, the idea of "position", due to the fact that there are innumerable instances of position in real life (which makes "position" more general than specific) whereas there is no instance of "biscuit A" other than itself (which makes "biscuit A" more specific than general).

However, it is also feasible to say that such a statement is not necessarily true because we may as well think of multiple instances with which "biscuit A" is associated, such as a photo taken from "biscuit A", a speech witnessing the presence of "biscuit A", a written letter about "biscuit A", a mirror image of "biscuit A", and so forth.

One may say that taking these examples as direct instances of "biscuit A" is pure nonsense because they are merely secondary sources and can never be as vivid as an actual sight of "biscuit A" which is something only our bare eyes are capable of witnessing. Such an assertion, however, is groundless from a cognitive point of view because no observation, regardless of how lucid it might be, can be a decisive evidence of the existence of "biscuit A". What we think we just saw with our bare eyes could have been a deliberate illusion, you know.

And since no observation can possibly provide us with the utmost degree of confidence as to the truthfulness of whichever object we are dealing with, the best methodology we may safely employ is to assume that the truth lies somewhere at the center (i.e. average) of our cloud of observations. Such is the virtue of statistics, and its empirical worldview justifies itself not based on some kind of tautology, but on our collective faith that it is "least biased".

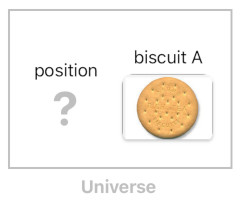

Let me just suppose here that there are two universes. One is simply the universe I have hitherto been talking about, and the other one is what I would refer to as the "anti-universe".

In our regular universe, a biscuit is something real and can be perceived directly; it is as close to the threshold of our sensation as it can manage itself to be. "Position", on the other hand, is a general concept and is therefore never visible to us.

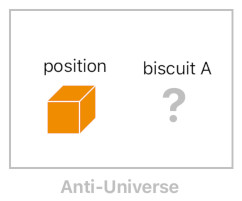

In the anti-universe, everything is reversed. People who dwell in this "upside-down" world never recognize a biscuit as something perceivable; to them, a particular biscuit such as "biscuit A" is the most abstract idea one can ever come up with.

In contrast, the idea of "position" is recognized as a tangible object here. It is an indestructible solid cube occupying the center of everybody's field of view, and is always available to be seen, touched, and even licked (It tastes like a canned cherry).

How, then, will we ever be able to convince the citizens of the anti-universe that "position" is indisputably abstract and "biscuit A" is indisputably tangible, other than by the evidence of our own cognitive tendency?

(Will be continued in Part 6)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service