Author: Youngjin Kang Date: May 28, 2024

(Continued from Part 3)

There is no way for us to directly observe a universal, since it is not equal to any of its instances. The idea called "biscuit" is a universal because it is present in all of its corresponding particulars (i.e. actual biscuits which we are able to see, smell, touch, and eat), yet can never identify itself with any one of them specifically.

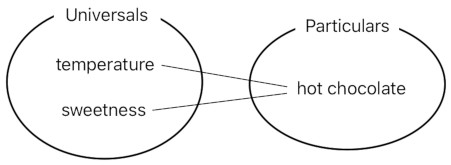

Dimensions, too, are universals because they are shared by multiple objects. "Temperature" is a universal because many things in our world possess their own degrees of temperature. "Sweetness", too, is a universal because there are many sweet things in our world, such as a piece of cake, a cookie, a candy, and so on, which have their own levels of sweetness.

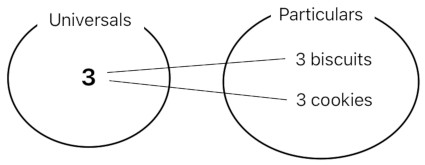

And you know what? Numbers, too, are universals because they are being shared by multiple objects. A jar of 3 biscuits and a jar of 3 cookies are two separate instances, yet they both share the same universal called "3".

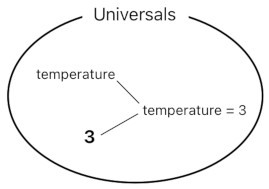

A temperature of degree 3 and a temperature of degree 4 both involve the same universal called "temperature". Here, however, we must behold that these two specific quantities are themselves universals, rather than particulars. The reason is that there could be multiple objects which have the same exact temperature.

Here is the main takeaway. A universal is generic in nature, but there are universals which are even more generic than other universals. The idea of temperature being equal to 3 (i.e. "temperature = 3") is generic in the sense that it can be shared by multiple objects whenever their temperatures are all measured to be 3 in magnitude, yet such an idea itself is still rather more specific than the more fundamental ones such as the idea of "temperature" and the idea of "3".

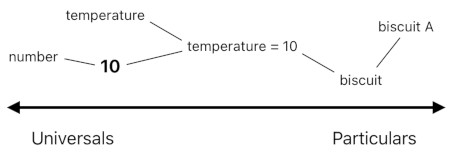

This sort of realization soon leads us to the conclusion that it is a bit pointless to try to divide everything into two disjoint classes called "universals" and "particulars". Some things may be more universal than others, and some things may be more particular than others, but does it suggest that we are absolutely required to establish a rigid boundary between these two concepts? Just like brightness and darkness, they may as well simply indicate the two opposing directions in a continuous spectrum.

Thus, it seems that one does not have to explicitly label every single thing as either "universal" or "particular", as these words merely represent the level of abstraction which is not strictly binary in nature.

The primary aim of what has been explained so far, is to get rid of our reliance on the concept called "dimension". As I have mentioned previously, a degree of temperature belongs to a dimension, a level of sweetness belongs to a dimension, and pretty much anything which can be denoted by a quantity belongs to a dimension. And the most annoying part of this is that, if we keep inventing new dimensions, we will soon be overwhelmed by the necessity to keep track of all of them.

And because of this reason, I will introduce here a more general definition of reality which transcends beyond a mere listing of numerical quantities.

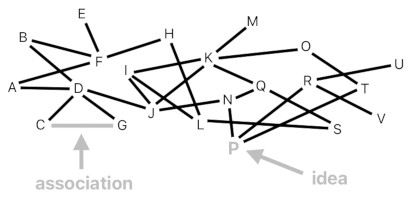

Our universe is a vast network of ideas. Each idea is any "thing" we can think of in our mind; it could be a tangible object, a sensation, an impression, a word, or pretty much anything we are able to express in our language.

Ideas are either associated or not associated with each other, depending on whether conceiving one of them lets us conceive the other. In this model of the universe, each idea is rendered as a unique symbol (e.g. an alphabet) and each association between ideas is rendered as a line segment.

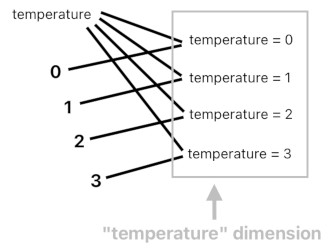

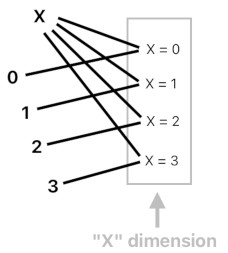

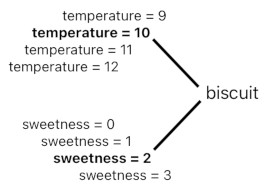

Each dimension is nothing more than a small subset of this network of ideas. The temperature-dimension, for example, is the set of all ideas which denote varying degrees of temperature, such as "temperature = 0", "temperature = 1", "temperature = 2", and etc.

A dimension is simply what we get by grouping a bunch of similar ideas together; it is by no means the most fundamental building block of our body of thoughts.

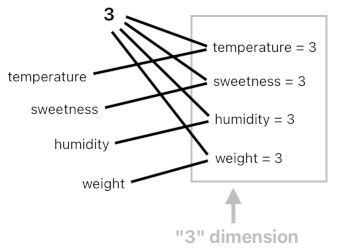

Here is a key observation which will support the statement I just made. As you can tell from the diagram above, the temperature-dimension is what you get by gathering all ideas which share the word "temperature" but do not share the same numerical value. In contrast, you can also imagine that it is equally feasible to gather all ideas which share the same numerical value (e.g. "3") but do not share the same word. An example of such a scenario is shown below.

A number which belongs to this alternative dimension tells us which characteristic of the object corresponds to the value of 3. Such an uncommon way of expression may hardly be useful for practical purposes, but it is nevertheless a perfect demonstration of the fact that a dimension is not a magical entity imbued with its own irreplicable qualities.

It feels like there is a clear difference between a dimension and a non-dimension, though. We are not likely to come up with a dimension just by picking a bunch of random ideas and putting them in a sequence, since the result is almost guaranteed to be meaningless. It is only when a sequence has at least one common idea (e.g. "temperature") as well as a range of numerical values to grant a sense of variability to such an idea, that it will qualify itself as a dimension.

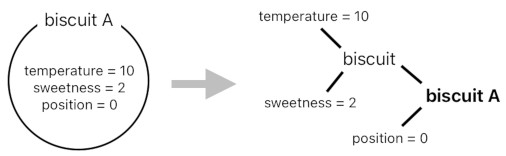

Letting an object have its own inventory of traits, after all, is basically the same thing as associating the object with ideas which correspond to those traits.

Let us suppose for now that all biscuits in our hypothetical universe possess the same exact temperature and sweetness (which is obviously not true in the real world, but let us just pretend that it is so, for the sake of illustration). As long as such a supposition holds, the idea of "biscuit" should be directly associated with their common temperature as well as their common sweetness.

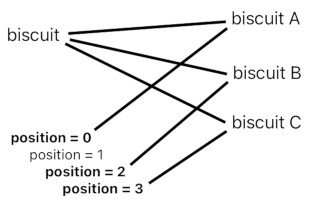

Individual biscuits, however, must have their own unique positions (unless we want all of them to be perfectly overlapping each other in one place). Therefore, each of the particular instances of "biscuit" will need to be directly associated with a position.

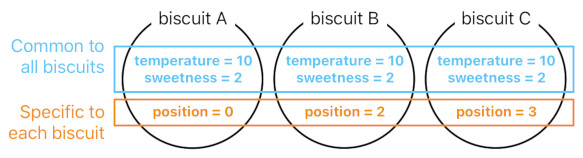

All biscuits have the temperature of 10 and sweetness of 2 because the idea of "biscuit", which simultaneously represents every single biscuit that can ever exist in this hypothetical universe, is directly associated with "temperature = 10" and "sweetness = 2".

On the other hand, specific instances of "biscuit" (such as "biscuit A", "biscuit B", and "biscuit C") have their own positions because they are directly associated with their corresponding positional quantities (i.e. "position = 0", "position = 2", and "position = 3").

While each particular biscuit can be thought of as carrying its own list of attributes such as "temperature", "sweetness", and "position", the question of whether an attribute shares the same exact value across all biscuits depends on the manner in which it is wired up in our grand network of ideas. A direct connection indicates something that varies across individuals, whereas an indirect connection indicates something that is common to all.

I have mentioned before that it is undesirable to try to represent an object with a gigantic list of numbers (dimensions) due to its inherent complexity. Now that we know that such numerical attributes are nothing more than associations among ideas, I guess we can all agree on the feasibility of fully describing an object not based upon a list of numbers, but based upon the way in which the object is associated with other ideas.

From a metaphorical perspective, I would say that each object is essentially a molecule made out of a set of conceptual atoms (i.e. ideas) and their chemical bonds. Once we figure out the chemistry of our mind, we will be able to design chemical equations to reflect the mechanics via which our thoughts combine, split, and rearrange themselves whenever they happen to be in proximity with one another.

Daydreamy tangent aside, here is another noteworthy advantage of structuring things as a network of ideas.

I have been naming things with well-understood words, such as "3", "temperature", "biscuit", and the like. However, each of these words is nothing more than a mere symbol, only meant to be a reference to the "real thing" which exists somewhere else. The idea of a biscuit is not the same thing as the word "biscuit", for instance, since we are able to think of a biscuit without spelling the word "biscuit" in our mind.

We do need some representation (i.e. image) of a biscuit to be able to imagine it, but the word "biscuit" is not the only symbol which can possibly serve the role of such a representation. One may as well use the term "solid-state complex carbohydrate" to indicate the same exact thing without incurring any logical contradiction.

Thus, we cannot assume that an idea must be endowed with a specific meaning just because it has a specific name. What gives meaning to an idea is the way in which it is being related to other ideas, not how it is being referenced in our language.

(Will be continued in Part 5)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service