Author: Youngjin Kang Date: May 25, 2024

(Continued from Part 2)

Baking is a complex procedure. Inside the oven, we have a composition of various ingredients which chemically interact with one another in subtle ways as they get heated up. How quickly the temperature rises and falls, how long a certain degree of temperature persists, how humid the air is, as well as in what shape the dough is posing on the plate, all contribute to the characteristics of the resulting delicacy.

Trying to capture the intricacy of such a work of culinary art in the form of a mere conversion from one number to another does feel incomplete, doesn't it? Using a single numerical quantity to illustrate all the aforementioned details is indeed too much of an oversimplification.

What should we do, then? Fortunately, it is not hard to imagine a decent solution. If using a single number is not enough, just use more numbers to represent more complex things.

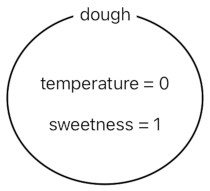

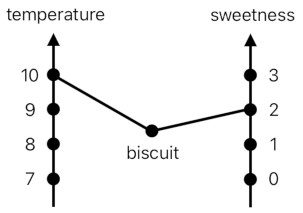

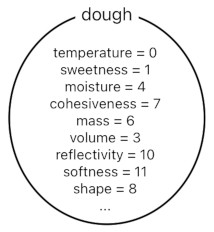

Here we have a piece of dough. Its temperature is 0, and its sweetness is 1. Let us take a look at another example.

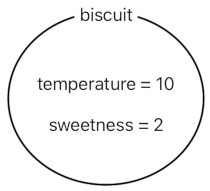

This is a biscuit. Its temperature is 10 (Pretty high because it just came out of the oven), and its sweetness is 2.

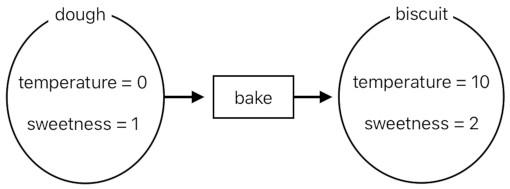

As the two figures above demonstrate, both the dough and biscuit are characterized by two numbers instead of just one. One of them indicates the temperature, and the other one indicates the level of sweetness. We are dealing with multidimensional entities here.

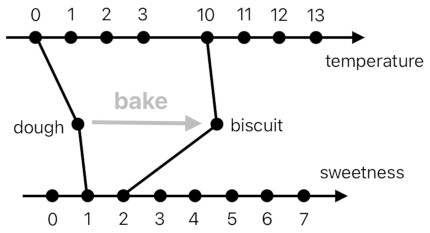

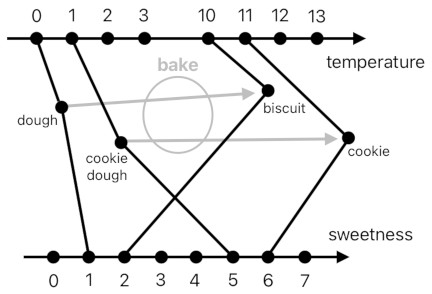

So, if the dough is made up of two numbers and the biscuit is also made up of two numbers, how shall we then describe the nature of the baking process which supposedly transforms a piece of dough into a biscuit? Let us first take a quick look at what is going on here.

The "bake" function, unlike in the previous example where it was only responsible for converting one number to another, is now responsible for converting a pair of numbers (0,1) to another pair of numbers (10,2). This doesn't look like a simple one-to-one relation anymore, or does it?

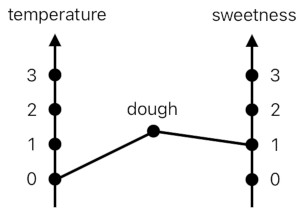

Think of "temperature" as a number which belongs to one dimension, and "sweetness" as another number which belongs to another dimension. We can then model these two as points in two separate number lines, which leads us to imagine the dough as some kind of "joint" between its temperature and sweetness.

The same logic applies to the biscuit.

The dough has the right to identify itself as "dough" because it is associated with 0 in the temperature-dimension and 1 in the sweetness-dimension. The biscuit has the right to identify itself as "biscuit" because it is associated with 10 in the temperature-dimension and 2 in the sweetness-dimension.

The act of baking a piece of dough, then, can best be rendered as a transformation of the "dough" joint into the corresponding "biscuit" joint.

In general, what the "bake" function really does is highly intuitive; it simply maps a group of joints to another group of joints in a pairwise manner. In colloquial language, this can be worded as an act of simultaneously modifying both the temperature and sweetness of the given input.

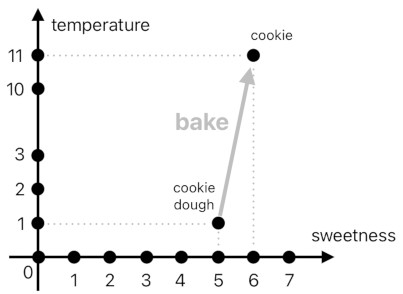

A more consistent way of illustrating this phenomenon is to orient the two dimensions perpendicularly to each other, and use them as the axes of a two-dimensional space. Each object (i.e. anything that has both temperature and sweetness), then, can be drawn as a 2D point.

The chief benefit of such a representation is that you are now able to consider the "bake" function as a physical force which pushes a particle from one location to another. The particle's current location tells us its current state (i.e. temperature and sweetness), and the "bake" function can be imagined as some kind of "force field" which, like an ocean current, initiates a flow from one position to another.

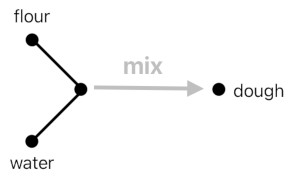

Analogies aside, it is now time to explore other cases. We have seen that, in order to manufacture a dough, we have to mix flour with water. Such a process of mixture can be modeled as a function called "mix", which receives both flour and water as its inputs and produces a piece of dough as the output.

This one is slightly more complex than the "bake" function because it handles two inputs instead of just one. Such a level of detail is not so difficult to elaborate, though. Just like the dough and the biscuit could each be considered a combination between the two attributes called "temperature" and "sweetness", the input port of the "mix" function could as well be considered a combination between the two inputs called "flour" and "water".

But here is something much trickier. When we were dealing with only a piece of dough and a biscuit, we were only obliged to compare their temperature and sweetness for the sake of distinguishing one of them from the other. Since we now have two new types of objects called "flour" and "water", we must somehow figure out a way to distinguish them from the previous two.

For example, just by comparing temperature and sweetness, can we tell the difference between "flour" and "dough"? Somebody may argue that such a comparison is feasible because dough may be slightly sweeter than flour and so on, yet such case-by-case circumvention is not going to solve the ultimate cause of the problem.

As we attempt to compare more and more types of objects, we inevitably feel that we need to introduce more and more numbers (i.e. dimensions) to the scene for the purpose of classification.

In order to express the wetness of water, shall we create a new number called "moisture"? In order to express the hardness of a biscuit, shall we create a new number called "rigidity"? Also, in order to express the high separability of the individual grains of flour, shall we create a new number called "cohesiveness"? The list goes on.

How to mitigate such labor? For sure, we do not want to force every single object to carry a gigantic bag of properties in it. Having to deal with a plethora of dimensions is such a headache everyone wants to avoid.

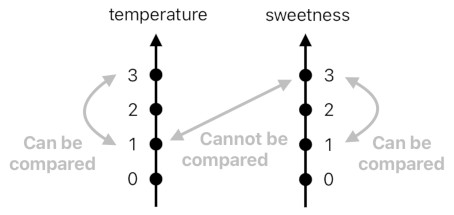

The origin of the pain we are facing here is that, for instance, our faculty of senses does not allow the feeling of temperature and sweetness to be compared with each other in any rational manner. Aside from the realm of metaphors, it is not so universally agreeable to claim whether the hotness of a microwaved cheeseburger is supposed to be "greater" than the sweetness of a chocolate mousse cake; such a comparison is so irksomely subjective, that one has no choice but altogether abandon such a poetic kind of ponderance when it comes to scientific reasoning.

And due to their nature of mutual incomparability, temperature and sweetness are compelled to reside in two separate dimensions.

The incompatibility among different categories of sensation (e.g. brightness, loudness, smell, taste, pain, ecstasy, etc) is what necessitates us to keep adding more and more dimensions to our context of reason, thus plunging ourselves into the infernal crucible of numerical demons whose full-time job is to torment us forever with their contrived arithmetic puzzles.

We cannot escape this prison of complexity as long as we continue thinking solely in terms of dimensions. It confines our mind to the belief that, whenever we see something in nature which is measurable (i.e. can be specified as a quantity), we have no choice but simply come up with a new name for it. This sort of approach is unsustainable because it forces us to carry an ever-growing list of definitions on our backs.

In order to think outside of the box of dimensions, we must stop focusing too much on the nitty-gritty technical aspects of how we may distinguish one thing from another, and really try to rethink the way in which we define "things" in our universe.

There are innumerable things in our world which we can either observe or imagine. And we have an intuitive understanding that some of them are more generic than others.

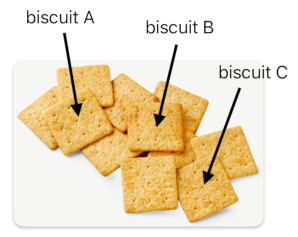

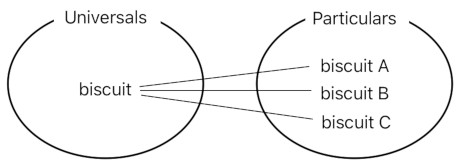

When I see a collection of biscuits, I do recognize each one of them as a separate object. I may randomly pick three of them and give them unique names such as "biscuit A", "biscuit B", and "biscuit C".

Yet, I am also aware that these three biscuits are nothing more than particular instances of the same underlying idea called "biscuit". They may be distinct from one another in the sense that they belong to different positions and so forth, but they nevertheless share the same essence in the sense that they are all being referred to as "biscuits".

To conceptualize what is being expounded here, I will introduce two classes of things - namely, "universals" and "particulars".

A universal is a common characteristic which is being shared by multiple objects. A particular, on the other hand, is one of such objects. Biscuit A, biscuit B, and biscuit C are all particulars because they are instances of the same universal called "biscuit".

(Will be continued in Part 4)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service