Author: Youngjin Kang Date: May 18, 2024

First of all, let me suggest that food is our common denominator of interest. There are people who are not interested in sports, religions, politics, and the like, but there is absolutely no one who is not interested in eating at all (If there is one, that dude is dead).

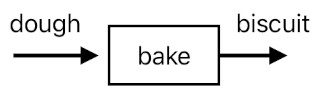

And guess what? Since we like food, we must seek ways of obtaining it. Let's consider a biscuit as an example. One of the most obvious ways of acquiring a biscuit is to bake a piece of dough.

biscuit = bake(dough)

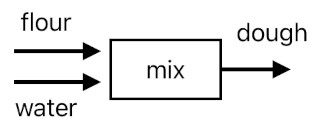

But in order to do that, we must first have a piece of dough in our hands. Let's make one, then, by mixing flour with water.

dough = mix(flour, water)

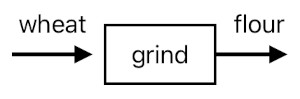

We can obtain flour by grinding wheat.

flour = grind(wheat)

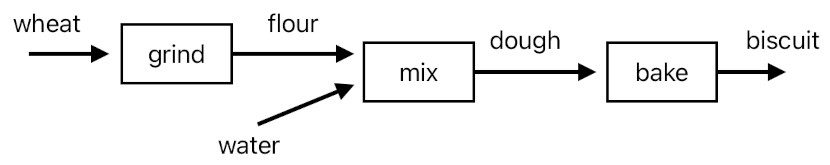

To summarize, we can generate a biscuit by mixing ground wheat with water and baking it.

biscuit = bake(mix(grind(wheat), water))

I will explain the notations shown so far. "bake" is a function which takes dough as the input and produces a biscuit as the output, and "mix" is a function which takes flour and water as the input and produces dough as the output. "grind" is a function which takes wheat as the input as produces flour as the output. If you assemble these functions together in the right way, you will get a biscuit.

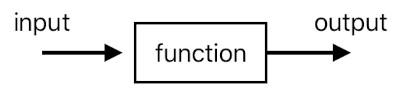

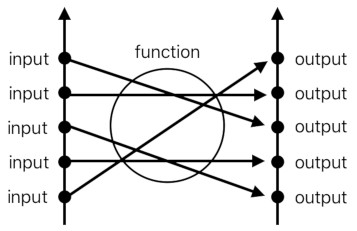

What is a "function", then? There are many ways of defining it, yet perhaps the most intuitive way is to consider a function as a little machine which has its own entrance and an exit. Through the entrance (aka "input port") it receives the ingredient, and through the exit (aka "output port") it spits out the result of manipulating the ingredient.

Whenever you choose to gather a multitude of such machines and compose them in order to produce the result you desire, you are building a factory where the individual workers collaborate with one another in a streamlined manner. The output of one worker could be handed over to another worker as the input, or multiple workers could be grabbing the same input and working on it concurrently so as to double the speed of production, and so on. There are so many possibilities here, and they can all be realized by joining functions with each other in creative ways. It all boils down to a network of input-output relations.

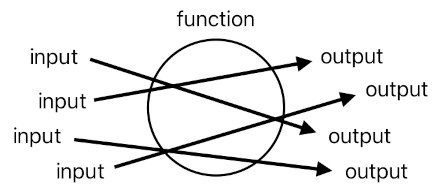

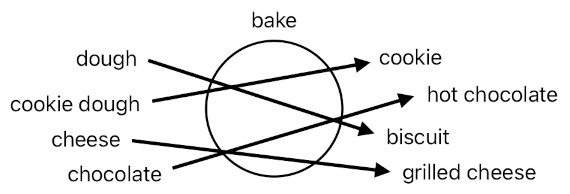

There is yet another way of defining what a function is, though. If you contemplate upon the meaning of a function in terms of what it does, you will soon come to the conclusion that a function is, on a purely conceptual level, just a bunch of connections between all of its possible inputs and their corresponding outputs.

Each connection (represented by an arrow) tells us which input values translate into which output values. For instance, the "bake" function can be identified as a set of connections between raw materials and their baked results.

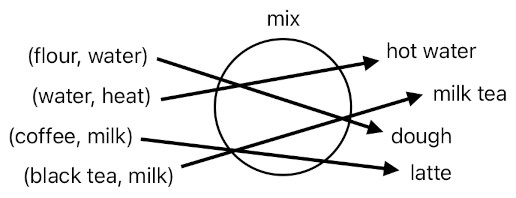

What about a function which takes a pair of ingredients as the input instead of just a single ingredient? The "mix" function is a typical example of this; it "mixes" the two given ingredients and produces a mixture between the two as the output. In this case, we can consider each connection as one which maps a pair of input elements (instead of just a singular input) into their corresponding output.

This kind of representation is fine, for the purpose of providing us with a means of understanding what a function does. There is something quite annoying in this approach, however. As you may have noticed already, it is way too cumbersome to describe a function by mentioning every one of its input-output relations. For a very simple function it might be manageable, but for a fairly complex function it is prohibitively laborious.

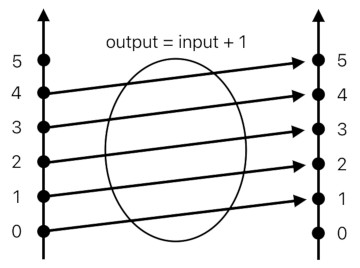

What do we do, then? If taking all possible input-output relations into account proves itself to be too difficult, the other solution we ought to follow is to specify the general pattern in which inputs are being associated with their respective outputs. And in order to do that, we must establish a way to somehow "align" all the inputs (as well as outputs) in the form of an ordered sequence. This will give them a structure to fit in, thereby enabling us to render their behavior in terms of a generally applicable rule rather than an enormous collection of case-by-case scenarios.

Here, we are grouping all the possible inputs as an ordered sequence (represented by a long vertical arrow). Also, we are grouping all the possible outputs as yet another ordered sequence. The reason why we are doing this is to keep things organized.

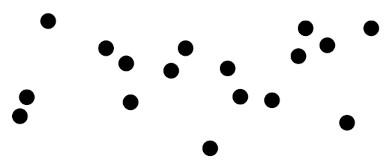

As we ponder upon the very nature of what the so-called "inputs" and "outputs" really are, we quickly come to the realization that there is not really an intrinsic difference between things that are labeled as "inputs" and things that are labeled as "outputs"; an output of a function can also be an input of another function, and vice versa. Inputs and outputs are both "things" which, in the most unbiased mode of representation, can best be depicted as a set of points in empty space.

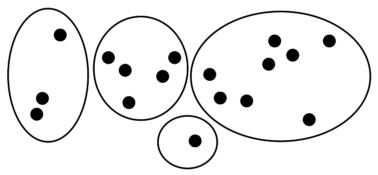

Oh, but here is where the trouble comes! Since there are so many things in our world to keep track of, we cannot just randomly plot them on a gigantic sheet of paper and try to make sense of them; such an undisciplined approach will make everything extremely confusing. What do we do, then? For sanity's sake, we organize them in some way or another. And one the most straightforward ways of organizing a bunch of things is to group them into categories.

For example, a variety of sandwiches, such as "chicken sandwich", "tuna sandwich", "meatball sandwich", "BLT sandwich", "PB&J sandwich", and the like, can all be grouped into the same category called "sandwich". The same logic applies to different breeds of a biological specie, different chemical elements in the periodic table, and so forth.

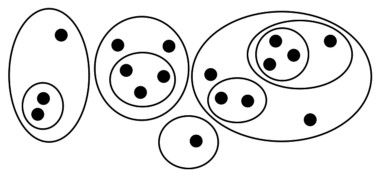

This sort of classification is still not enough, though. A category may turn out to be too broad in scope, that there are still way too many unorganized things lurking inside each category. This impels us to keep introducing new categories within our existing categories, thus giving birth to a taxonomical hierarchy.

As we do this, however, we begin to complicate things rather too much. It is usually not so high a virtue to have Russian dolls in one's faculty of reasoning, and it is important for one to admit that a more sustainable method of keeping things under control is to order them in the form of a sequence.

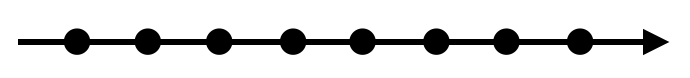

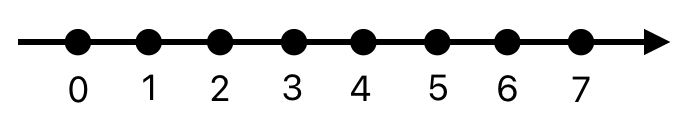

The long arrow shown here is a sequence, which bears a direction as well as the sense of alignment. Elements of this sequence either come before or after one another, depending on which of them are closer to the head of the arrow than others, etc. And the most quintessential advantage of doing it this way is that it lets us refer to things with numbers instead of arbitrary names.

Numbers reflect the concept of order very accurately. 1 comes after 0, 2 comes after 1, and 3 comes after 2. By comparing numerical values, we can immediately tell ourselves whether a thing comes before or after another thing. And as we figure out the order of things, we acquire a key to unlock the secret of parallelism. Here is an example:

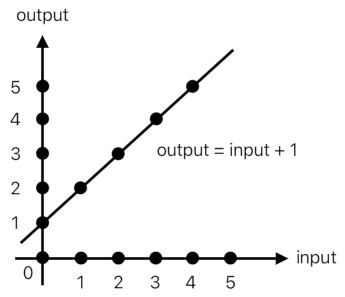

We are looking at a function which is characterized by the equation: "output = input + 1". It means that the output of this function is always the result of incrementing the input by 1. We do not have to list all possible inputs and their corresponding outputs to fully define what the function does, since the equation alone reveals all the clues we need to derive the output from any given input.

The reason why such an abbreviation is feasible is that this function only deals with numerical entities (i.e. things which make up a sequence when they are put together). Since the input is a string of ordered things and the output is also a string of ordered things, we can consider the function as some kind of "string manipulator" - a special gadget which absorbs a string, distorts it (using mechanical instructions such as: "Cut it!", "Stretch it!", "Shrink it!", etc), and emits the result.

If the input were a mere assortment of random objects (like a bottle of jelly beans), it would have been extremely difficult to figure out what to do with them exactly. As we tie them up on a rope and treat the whole body as a single entity, we begin to let ourselves move all these individual pieces at once by simply pulling the rope. In mathematics, such a rope is called a "number line".

Aside from the ease of operation, the aforementioned mode of thinking also lets us plot the function's input-output relations in the form of a graph, like the one shown below:

Such is the power of expressing things in terms of numbers, hence the reason why they are so commonly used in mathematics. But of course, numbers themselves do not mean anything unless we specify the context in which they are being used. If I just say "Three!", it will hardly mean anything. If I say that I have three eggs, on the other hand, it will definitely mean something which can be pictured in the listener's mind.

(Will be continued in Part 2)

Previous Page Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service