Author: Youngjin Kang Date: June 13, 2024

(Continued from Part 8)

All right, enough with the conveyor belt!

For the sake of not plunging too deeply into technical details, I will put a pause on the ongoing topic for now and go through the fundamentals.

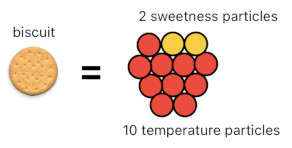

It has been mentioned that our world is made out of various things, and that such things can be expressed in terms of particles. Any object can be considered a combination of one or more particles. A biscuit, for instance, has been defined as the combination between 2 sweetness particles and 10 temperature particles.

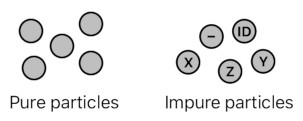

However, I have not explained yet how particles really interact with one another. In order to clarify some of the points which may have been seemingly vague, I will first start with "pure" particles - that is, particles which have no type at all.

Both sweetness and temperature particles are "impure" in the sense that they represent characteristics of real (tangible) objects. Pure particles, on the other hand, are "pure" in the sense that they are the most basic units of existence, devoid of any extra meaning.

Let us forget about biscuits and cookies for a moment, and start thinking in terms of pure particles and their elementary mechanics.

Particles are like tiny little bubbles. Some of them have names written on their faces, but such additional ornaments make them impure. Pure particles don't even have names; they are completely anonymous, just like innumerable little bubbles hovering in midair.

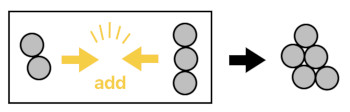

Imagine that a body of 2 particles and a body of 3 particles charge straight toward each other and collide in the middle. What is going to happen? Since particles tend to stick together when forced to be in one place, they bond to form a singular body of 5 particles. This is what it means to "add" two things.

2 + 3 = 5

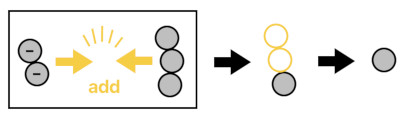

What if the body of 2 particles were made of anti-particles (denoted by "-") instead of regular ones? In this case, I would say that they are "impure" because they are imbued with the meaning of negation (-). They possess the ability of "cancelling out" their positive counterparts. So when a particle meets its opposing anti-particle, they combine to form 0, annihilating each other completely.

This means that, when 2 anti-particles collide with 3 regular particles, 2 of their opposing pairs will cancel each other out and disappear completely, leaving only 1 regular particle to remain. Such an event is what we call "subtraction"; we are subtracting 2 from 3 here.

(-2) + 3 = (-1+1) + (-1+1) + 1 = 1

The main takeaway is that, whenever we add two things, they stick together and form a single rigid body. We do not "mix" them in any way; we just put them together, so as to ensure that they are touching each other.

What happens when we multiply two things? A good way of understanding the nature of multiplication is to think of it as a process of "planting" one thing upon the soil of the other. You can plant a flower in two pots, and expect that these two pots will each be occupied by a flower later on, resulting in two flower-bearing pots in total. Such is the result of multiplying a flower by two pots.

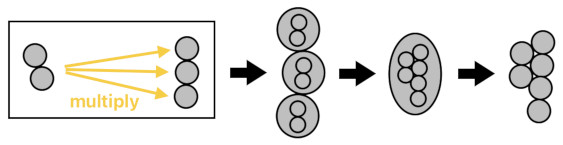

Similarly, multiplying a body of 2 particles and a body of 3 particles together basically "plants" the body of 2 particles upon the soil of the other 3 particles. The former 2 particles are like a pair of flowers we decided to plant in each pot, and the latter 3 particles are like a group of 3 pots, each of which is to be occupied by a pair of flowers. The result will be 6 flowers in total.

(2)(3) = 2(1) + 2(1) + 2(1) = 6(1) = 6

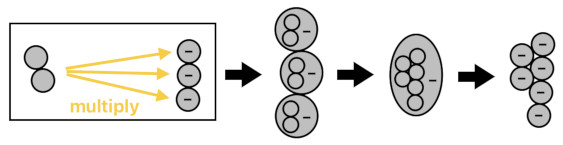

We can multiply anti-particles as well. When we multiply a body of 2 particles and a body of 3 anti-particles together, we are basically planting a pair of flowers in every one of the 3 anti-pots. Whenever we put a flower seed upon the soil of an anti-pot, it grows to become an anti-flower instead of a regular flower (i.e. Its petals are all inverted, etc). The result will be 6 anti-flowers (i.e. "-6 flowers") in total.

2(-3) = 2(-1) + 2(-1) + 2(-1) = 6(-1) = -6

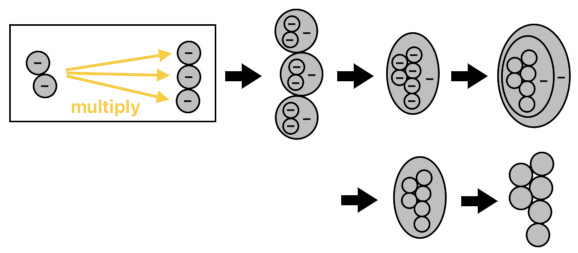

We can multiply a body of anti-particles with yet another body of anti-particles as well. Suppose that we decided to plant a pair of anti-flowers in each of 3 anti-pots. In each anti-pot, an anti-flower seed grows to become an anti-anti-flower. Since an anti-anti-flower is the same thing as just a regular flower, we will eventually see 6 regular flowers in total.

(-2)(-3) = (-2)(-1) + (-2)(-1) + (-2)(-1) = (-6)(-1) = 6(-1)(-1) = 6(1) = 6

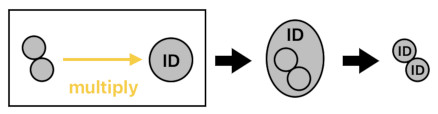

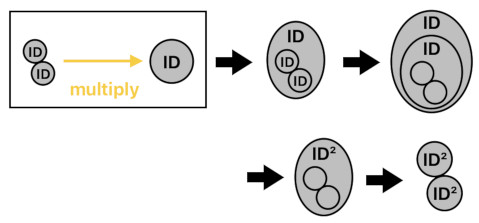

Previously, I have demonstrated that each body of particles (such as a biscuit) can have its own identity as long as they are endowed with a unique identifier such as "ID". Assigning an identifier can be done by means of multiplication, since the identifier itself is a particle with its own unique name (e.g. "ID").

When we multiply a body of 2 particles and a body of a single "ID" particle together, we are planting a pair of flowers in a single pot marked by the name "ID". So, when the two flowers eventually grow upon the soil of this special pot, we will be able to refer to these two flowers as "ID flowers" instead of just random, anonymous flowers that can be found anywhere in the garden. Each of these two special flowers will be named "ID" because their pot's name is "ID".

2 ID = ID + ID

What if we decide to plant these two "ID flowers" in a brand new pot whose name is also "ID"? The result is not too difficult to predict. When we plant a pair of "ID flowers" in an "ID pot", the pot will grow a pair of "ID flowers" and then attach an additional "ID" prefix to each of their names. This will turn them into a pair of "ID ID flowers", or, to put it in a more succinct manner, a pair of "ID² flowers".

(2 ID) ID = 2 (ID ID) = 2 ID² = ID² + ID²

What I have portrayed so far will give you the general idea of what multiplication does. Whenever we multiply two objects, we are begetting the children of one object inside the womb of the other object.

Multiplication of particles is a useful concept not only in the realm of pure numerical quantities, but also in the world of magic. If you are an undergraduate wizard who is majoring in Sorcery Engineering, you should pay attention to the fact that particles and their products of multiplication are the most basic building blocks of modern magic.

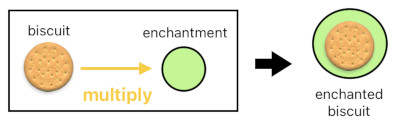

For example, you can enchant a biscuit by following the three steps below:

(1) Generate an enchantment aura.

(2) Hold this aura with your wand.

(3) Point your wand to the biscuit, and cast the "multiply" spell. This will enchant the biscuit by wrapping it with the enchantment aura.

RESULT: (biscuit enchantment) = "enchanted biscuit"

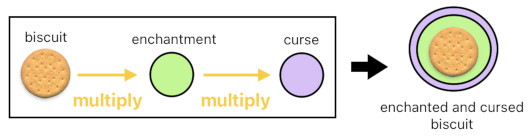

It is equally feasible to enchant a biscuit AND curse it also, since nothing prevents us from wrapping a biscuit with two layers of aura. You can do it by following the steps shown below:

(1) Generate an enchantment aura.

(2) Hold this aura with your wand.

(3) Point your wand to the biscuit, and cast the "multiply" spell. This will enchant the biscuit by wrapping it with the enchantment aura.

(4) Generate a curse aura.

(5) Hold this aura with your wand.

(6) Point your wand to the enchanted biscuit, and cast the "multiply" spell. This will curse the enchanted biscuit by wrapping it with the curse aura.

RESULT: (biscuit enchantment curse) = "enchanted and cursed biscuit"

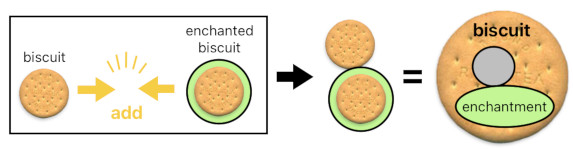

Just as a pure biscuit (i.e. biscuit without any aura) is an independent object, an enchanted biscuit is also an independent object. When we put these two objects together by adding them, therefore, their internal organs do not mix up in any way. These two objects, as a pair of rigid bodies, simply hold each other's hand, like a pair of magnets.

biscuit + biscuit enchantment = (1 + enchantment) biscuit

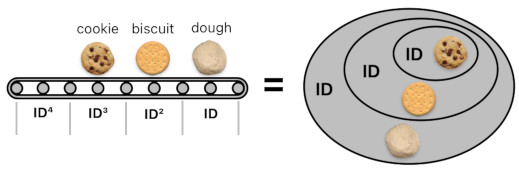

Let us go back to the conveyor belt analogy. In this peculiar model, we saw that each "position" upon the surface of the belt could be identified by a distinct power (i.e. repeated multiplication) of a variable called "ID".

What really happened here is that we put the belt's first (frontmost) object inside an ID aura, put this whole thing inside yet another ID aura (alongside the second object), and put this even bigger thing inside yet another ID aura, and so forth.

Thus, we could say that a conveyor belt which is made out of N discrete locations may as well be described as a body of N layers of ID aura, each of which contains each location's occupying object.

cookie ID³ + biscuit ID² + dough ID = (cookie ID² + biscuit ID + dough) ID = ((cookie ID + biscuit) ID + dough) ID

The same logic applies to other types of aura as well. For example, you can technically enchant an already enchanted biscuit, turning it into an "enchanted² biscuit" (i.e. "enchanted-squared biscuit"), and so on. If you enchant a whole sequence of biscuits with varying degrees of enchantment (That is, you enchant the 1st biscuit only once, enchant the 2nd biscuit twice, etc), you will be left with an "enchantment belt" of biscuits.

(Will be continued in Part 10)

Previous Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service