Author: Youngjin Kang Date: May 15, 2024

Math is an important subject. We learn it in order to have a better understanding of the world around us. It is also useful for various applications such as those pertaining to economics, natural sciences, engineering, and many others.

The process of learning math, however, is oftentimes a bit of a pain in one's anatomical bottom. And the main reason why this is so is that the way in which math is being presented to the public is dominated by an enormous heap of dry rules and nitpicky technical details. To be fair, what sort of crackpot would be delighted to spend one's nightly leisure time watching a silent interplay of numbers, points, lines, and Greek letters on a sheet of paper?

A book which deals with mathematical ideas is typically filled up with a truckload of abstract symbols, as well as numerous theorems, examples, and proofs which thoroughly dissect their meanings. Such a comprehensive method of breaking down what is meant to be conveyed to the reader is, without a doubt, the most sincere and effective means of organizing a mathematical treatise.

Such a thorough manner of presentation, though, usually baffles those who are not professional mathematicians and thus do not possess enough patience to follow all the tasteless details. To the reader who is already endowed with the holy spirit of mathematics, those esoteric Greek letters do imply something enjoyable. To the layman, they do not mean anything.

Sadly, many of us often feel the necessity to spend some time studying mathematics for the sake of staying competent in our modern world, which is being governed by economists, business professionals, scientists, and engineers whose expertise heavily depends on the understanding of math. And this tendency seems to amplify itself the more our technology advances.

The problem lies on the fact that, while we do need to learn math, most of its study materials are so painfully unapproachable. And I myself wholeheartedly share this sentiment as well, even though I am an engineer with a 4-year university degree in engineering; it often requires me to load my brain with at least 100mg of caffeine in order to fool it into thinking that an algebraic formula is something interesting to look at.

So, how to fix this horrendous discrepancy between the necessity to learn math and the sheer lack of motivation to do so?

There indeed have been many attempts to deal with this problem, especially among educators, which involved storytelling (as in "Algebra, the Easy Way" by Douglas Downing), interactive visuals, games, and other fascinating experiments in the domain of mixed media.

Yet, for some reason, they do not seem as mainstream as they should be. Core math curriculums in the majority of public schools still heavily focus on teaching a set of formal proofs and problem-solving methodologies, most of which are obsessed rather too much with the technical side of mathematical reasoning than the divine inspiration behind it. As a result, most students get tired of the perennial influx of details before they grasp a chance to find passion in the subject.

In order to alleviate this shared sense of frustration, some educators choose to motivate their students by trying to convince them how useful math is. They tell their students that cool inventions such as airplanes, gaming PCs, Ferris wheels, and ice-pooping refrigerators are all being made by smart people who know all the fancy math and stuff, and that we, too, can do similar cool things by memorizing a bunch of theorems and knowing how to apply them.

Such a type of motivation, however, inadvertently degrades mathematics into some kind of "necessary evil" - a bucket of unappetizing veggies you must force yourself to swallow for the purpose of achieving some distant goal. This confounding gap between the ends and means is what often separates us from the pure joy of thinking mathematically; it is just not as directly rewarding as, say, playing video games.

Many (if not most) of the dedicated mathematicians who study math "just for fun" are not the ones who study it for the sake of utilizing it as a means of something else. They enjoy math as it is, just like many artists take pride in creating art for art's sake and nothing else. It is a "thing in itself", an inexplicable yet quantifiable sort of ghost which is everywhere but is never directly visible.

How to let ourselves grasp such a profound breed of enjoyment without too much hassle, then? A straightforward answer is to keep exposing ourselves to the world of mathematics as much as possible until a tickling moment of enlightenment reveals itself before the face of our subconscious, by means of reading textbooks, solving math problems, following lectures, and so on. This, however, requires us to spend too much time and energy to stay in focus. There must be a better way.

Let us start from common sense. The number one reason why mathematics is uninteresting to most of us is that it looks so detached from our everyday life. Most of us just do not "see" math in things we experience daily, although it really is everywhere from an abstract point of view (In a way, it is the highest form of philosophy - the purest essence of what we can think of and reason with). This is because math is abstract by nature; we can only induce its presence from the collective sum of our experiences.

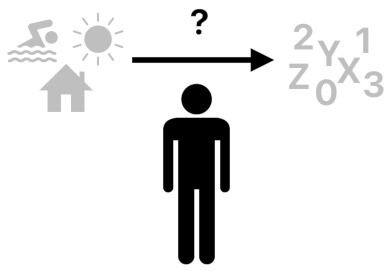

The key is to narrow down the gap between our senses and their underlying abstract implications. And since we can only elaborate our own thoughts in terms of what we can directly perceive (because even purely abstract ideas require us to use symbols to express them), we must start with experiences which are familiar to us and then figure out how to let them reveal their own gateways to the beauty of mathematics.

(To be continued)

Next Page

© 2019-2026 ThingsPool. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy Terms of Service